www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/reviews/unsettling-outdoors-environmental-estrangement.html

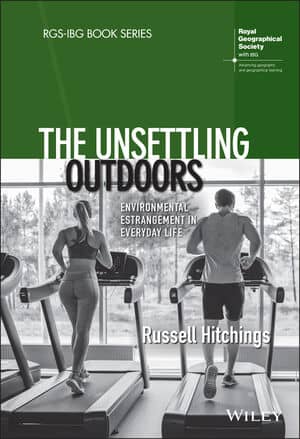

The Unsettling Outdoors: Environmental Estrangement in Everyday Life

By Russell Hitchings. RGS-IBG with Wiley, 2021, ISBN: 978-1-119-54915-4.

Sarah Royston reviews this book about the intersection between urban lives and green spaces.

From burgeoning research on nature-deficit disorder (Louv, 2005), to the cultural phenomenon of the Lost Words project (Macfarlane and Morris, 2017), awareness is growing of environmental estrangement in modern urban lives. Despite extensive evidence on the benefits of outdoor experiences for wellbeing, and for engagement with environmental issues, we seem to be spending less time in contact with the natural world. In his fascinating new book, Russell Hitchings argues that particular patterns of living are systematically reducing city-dwellers' engagement with green spaces. Through four case studies, exploring how people work, exercise, garden and keep clean, he shows how daily routines increasingly alienate us from outdoor experiences.

A key contribution of the book is in forging links between geographies of nature and theories of social practice, so as to explore the kinds of (dis)connection with outdoor environments that arise through the performance of various everyday activities. Hitchings not only documents the "extinction of experience" (Pyle, 1993), but reveals the insidious and systematic ways in which specific patterns of work and leisure are effectively editing greenspace out of urban lives. The in-depth focus on mundane routines enables the analysis to go beyond generalised statements about estrangement from nature, to examine specific dynamics of forgetting, avoiding, succumbing and embracing that play out in particular contexts. However, the overall implication of the book seems to be that forgetting and avoiding are the most powerful of these, with an embracing of nature only observed as a temporary disruption to normality within the short timeframe of a music festival.

Reflecting on Hitchings' four case studies, one can see recurring spirals of loss and degradation, not just in experience and interest, but in vocabularies, norms and skills. In a revealing example, when asked to describe their gardens, some participants lapsed into a bemused silence; the book highlights narrowing repertoires of speech, thought and action. One disturbing finding concerns a perception that engaging with nature is eccentric or weird, with an "outdoor alibi" (p63) (such as running an errand) needed in order to legitimise such peculiarity. Some office-workers were so imprisoned by the interlocking constraints of work cultures and temporalities that they reported only a vague awareness of the present season and weather. Meanwhile, there are associated losses in skills, such as know-how for adaptive comfort that responds to the vagaries of outdoor environments. The picture painted by this book - a collective sleepwalk into a lifeless concrete world - can certainly be described as unsettling.

More

widely, the book opens up exciting questions about how nature and outdoor

experience can be understood within a practice-theoretical analysis. For example,

Hitchings' analysis focuses mainly on tensions between practices and the

outdoors, rather than on 'positive' entanglements. The four dynamics that he

identifies are compelling in their own right, but also serve as an invitation

for further research: we might wonder what kinds of nature-engagement are

demanded by other forms of practice, for other practitioners. In what ways do

everyday routines facilitate, say, nurturing; stewarding; observing; or creatively

engaging with green spaces? In what ways might such routines be fostered and

supported?

The book is also remarkable in its methodological contribution, serving as a model for qualitative research that takes social practice seriously: reflexive, opportunistic, unapologetically fascinated by the mundane, and fundamentally respectful of participants' expertise in their own lives. Hitchings tackles critiques of talk-based practice research head-on, offering a carefully-reasoned justification of interview methods: not claiming that they give an objective 'window' onto participants' lives, but rather understanding talk itself as practice, and attending to real-life ways of speaking in specific moments, and what they can (and cannot) tell us about the speaker's experience.

Drawing on several years of field research and over 180

interviews, Hitchings is unafraid

to provide the kind of messy detail that journal papers often skim over.

Through frank accounts of the methodologies used, he unsettles notions of what

an interview is and should be. The data collection involved a mingling of observation

and participation, along with interview-conversations that were often responsive,

informal and mobile, including 'running interviews' with runners. The book

offers particularly valuable advice for those researching 'banal'

subjects, which can be challenging to study. It illustrates how researchers

might use instances of disruption to illuminate the normal, how photo-taking can

stimulate discussion of everyday environments, and how different question

framings open up new ways of thinking. The analysis pays attention to what is

unspoken, dodged

or deflected, and the strategies deployed, with thoughtful reflection on

details such as use of the passive voice and laughter. The result is not only a

rich set of findings, but a hugely valuable resource for students and other

researchers interested in applying creative qualitative approaches to everyday

life.

The book

raises significant challenges for professionals involved in urban policy,

planning and design. Critically, it shows how promoting outdoor experience is

much more than an issue of provision of urban green spaces. Nor is it simply a

matter of raising individuals' awareness of green-space opportunities or

benefits. This analysis reveals the importance of considering outdoor

experience in the context of the many intersecting routines that make up city-dwellers'

lives. Arguably, one implication of this is to massively broaden the scope of

what we consider to be a green-space policy or intervention (as has been

demonstrated in other fields, e.g. by Royston et al., 2018). Building on work

linking active travel with green-space (e.g. Le et al., 2018) we might think of

urban travel policies as green-space policies, and ask how they act to obstruct

or facilitate outdoor experiences. Going further, how might green-space

engagement be supported by interventions aimed at workplace cultures or timings

of the working day?

Hitchings' analysis challenges decision-makers and planners to think about designing for lives that include outdoor experience as a matter of routine. What might such ways of life look like: not just in terms of space and infrastructure (though these are important) but in time, in skills, in understandings of what is normal? For example, as well as considering the size of private gardens, we might ask whether people have opportunities to develop the practical skills and vocabulary to engage with the spaces they have. This might lead us to think about supporting community gardens where such skills can be shared. If just 'being in nature' is seen as eccentric, we might think about fostering different 'legitimate' forms of outdoor practice. For example, could local authorities provide or support outdoor exercise classes (and suitable dog-free spaces for them)? Architects might take into account the need to create time-space for acceptable outdoor experience within work environments, for example, providing 'outdoor meeting rooms' or 'outdoor desks' using office roofs or courtyards.

For

researchers, Hitchings highlights interesting topics for further study in the

field of urban green-space, including the roles of weather and climate; technology

and time; and dirt and disruption. He also draws attention to the influence of

intermediaries such as garden-designers, highlighting an underexplored area within

green-space research (which mostly focuses on residents). This insight also represents

an invitation to these professionals themselves: to recognise that they have a

key role to play as makers and shapers of outdoor practices. Ultimately (and as

the COVID pandemic has powerfully shown) routines are never fixed, and can be

disrupted in all sorts of ways.

With

a down-to-earth style, Hitchings' work embodies urban geography at its best -

rooted in creativity, reflexivity, theoretical insight without dogma, and a

deep attentiveness to the entanglements of human and beyond-human worlds. The

book is not only a valuable resource for researchers and students in geography,

planning and the built environment, but also a fascinating and engaging read.

References

Le, H.H.K, Buehler, R. and Hankey, S. (2018). Correlates of the built environment and active travel: evidence from 20 US metropolitan areas. Environmental Health Perspectives, 126:7. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP3389.

Louv, R. (2005). Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. New York: Algonquin Books.

Macfarlane, R. and Morris, J. (2017). The Lost Words. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Pyle, R.M. (1993). The Thunder Tree: Lessons from an Urban Wildland. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Royston, S., Selby, J. and Shove, E. (2018). Invisible energy policies: A new agenda for energy demand reduction. Energy Policy, 123: 127-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.08.052.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.