www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/will-ndc-drive-buildings-breakthrough.html

Will NDC 3.0 Drive a Buildings Breakthrough?

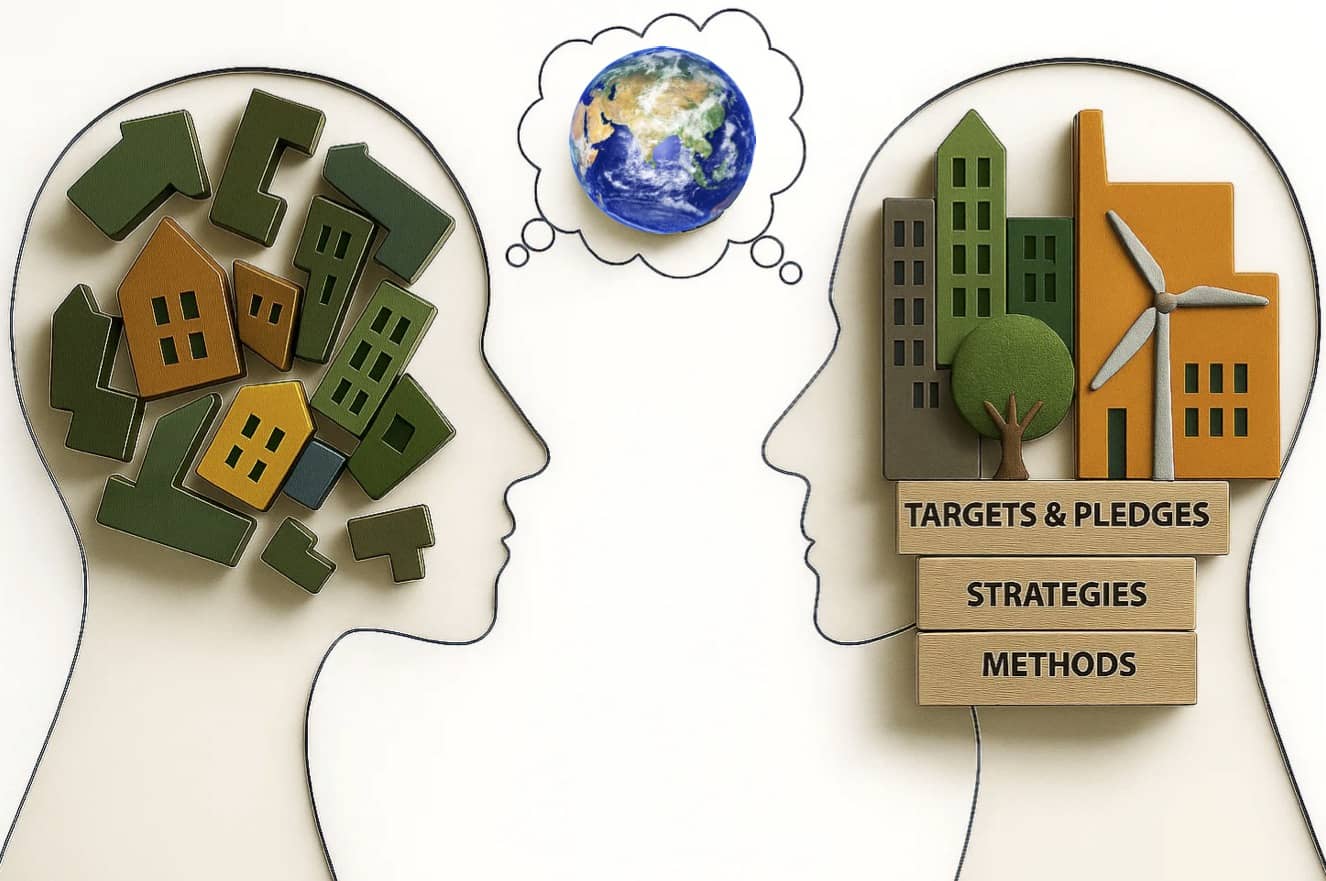

Why policymakers should create mitigation roadmaps for construction and real estate

To achieve net zero GHG emissions by mid-century (the Breakthrough Agenda) it is vital to establish explicit sector-specific roadmaps and targets. With an eye to the forthcoming COP30 in Brazil and based on work in the IEA EBC Annex 89, Thomas Lützkendorf, Greg Foliente and Alexander Passer argue why specific goals and measures for building, construction and real estate are needed in the forthcoming round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC 3.0).

Based on the 2015 UN Paris Climate Agreement, signatory Parties are bound to update or revise their national pledges for GHG emission reductions in terms of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) every five years. The time has come again to do before the next COP30 in Belem, Brazil in November 2025. The next generation of NDCs (NDC 3.0) shall apply until 2035 and need to be more ambitious (Reddy et al. 2024), progressive and detailed than current ones.

We - the authors of this contribution - advocate that NDCs 3.0 must now go beyond an overall national mitigation goal and include specific breakdowns for major industries, economic sectors and fields of action. Clear sub-level goals for - among others - building, construction and real estate sector (BCR sector) need to be established, and specific emission reduction pathways and roadmaps need to be developed.

A critical sector for GHG emissions mitigation

The BCR sector has a major direct and indirect influence on GHG emissions, which needs to be included in individual countries' next NDC pledges. The evidence for doing so is clear. Since 2016, published data on the construction and building sector's direct, indirect and embodied emissions have been based on a cross-sectoral approach using the polluter-pays principle (GlobalABC 2016). Thus, they differ significantly from the national statistics of many countries, which normally follow the source principle and focus on the direct emissions caused only by the operation of buildings. These have led to a significant underestimation of the importance of the BCR sector for climate protection. GlobalABC's reports, which are based on data from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and covering direct and indirect operational GHG emissions as well as estimates of embodied GHG emissions of the global building stock, indicate that the share for the BCR sector is close to 40% of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. This magnitude has been confirmed in several studies at the level of some individual countries, e.g. (BBSR 2020), where they follow a comparable approach. This significant proportion is also an indication of the existing reduction potential.

An international rethink is required to significantly and urgently reduce the GHG emissions from the built environment. Increasingly, the potential for reduction is being recognised and is the subject of political action. In March 2024 the Déclaration de Chaillot (Buildings and Climate Global Forum 2024) - as one example for new actions at the international level - was launched with support from over 60 countries, and now, 46 countries have officially confirmed their formal participation in the Intergovernmental Council for Buildings and Climate (ICBC). The Déclaration expands on the Breakthrough Agenda, and the subsequent Buildings Breakthrough which sets the goal of making "near-zero-emission and resilient buildings the new normal by 2030" (GlobalABC 2025). This encompasses the entire life cycle and thus the direct, indirect and embodied GHG emissions, expressed as global warming potential (GWP). As of the end of May 2005, the Buildings Breakthrough has been endorsed by 29 countries and supported by the European Commission as well as 34 organisations and initiatives.

Net-zero GHG emission roadmaps and pathways for the BCR sector are being developed in some countries. In Europe, the EU has a requirement for its member states to develop and submit corresponding reduction pathways by the end of 2026 - see European Directive (EU) 2024/1275 on the energy performance of buildings (EU 2024). These reduction pathways will provide the basis for the derivation of binding requirements for limiting GHG emissions in the life cycle of new buildings. This shows that the special importance of the BCR sector for climate protection is increasingly recognised in politics and society. Because of this role and mitigation potential of the sector (sometimes also called construction and real estate industry or field of action construction and operation of buildings), it is now time for it to be explicitly and adequately considered in NDCs 3.0

Previous NDCs did not address strategies and measures to achieve net zero GHG emission buildings in their whole life cycle (also known as climate-neutral buildings). Only 18% of all former NDCs have quantifiable mitigation targets for the built environment (Reddy et al. 2024). To improve situation, numerous organisations have published various recommendations, aids and guidelines for policymakers to embrace in the creation of national climate protection plans, including specific ones for BCR sector. Some examples are shown in Table 1. The guidelines make suggestions on how to draw attention to buildings and/or the BCR sector, what actions are possible and how initiatives can be implemented and monitored.

Table 1: Examples of guidelines for integrating the building and construction sector into NDCs

| Name | Title and Link |

|---|---|

|

Programme for Energy Efficiency in Buildings (PEEB) Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction (GlobalABC) |

NDCs for Buildings: Ambitious, Investable, Actionable, and Inclusive |

|

World Green Building Council (WorldGBC) |

|

|

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) |

Compendium on greenhouse gas baselines and monitoring – building and construction sector |

|

UN Environment, GlobalABC |

|

|

PEEB |

Mapping Targets on Buildings in the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) |

|

United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) et al. |

Building Circularity into Nationally Determined Contributions: A Practical Toolbox |

|

UNEP, GlobalABC |

Adopting decarbonisation policies in the buildings & construction sector – costs and benefits |

|

NDC PARTNERSHIP |

Sectoral implementation of NDCs – Energy efficiency with a focus on buildings |

A common goal, different starting points and multiple pathways

The limitation of global warming is a common goal. It is vital to include significant emitters in each NDC. Any country has still the opportunity of making a significant, positive impact by adapting their next NDCs to include the BCR sector, taking into account specific situation and different starting points. It is not too late to do this now.

Although many countries are still finalising their NDCs, the following recommendations are provided to assist with the inclusion of the BCR sector:

- If there is no national legislation to improve the energy efficiency of buildings and/or to reduce operational, embodied or life cycle related GHG emissions, and if there are no mitigation pathways for the BCR sector, the importance of buildings could be highlighted as a general principle and participation in Buildings Breakthrough encouraged.

- Reference should be made to the extent that national legislation already exists to improve the energy efficiency of buildings and/or reduce GHG emissions. The achievable reduction potential should be estimated and indicated (considering direct, indirect and embodied parts) and clear mitigation goals established.

- If roadmaps and mitigation pathways for the BCR sector are already available, reference should be made to them and their mitigation potential should be indicated.

The creation of a national mitigation pathway for BCR sector is recommended. Table 2 shows examples.

Table 2: Examples of mitigation pathways for BCR sector

| Name | Title and Link |

|---|---|

|

Science-based Targets |

1.5°C Pathways for the Global Buildings Sector’s Embodied Emissions |

|

Chatterjee, S., Kiss, B., Ürge-Vorsatz, D., Teske, S. (2022). |

Decarbonisation Pathways for Buildings. In: Teske, S. (eds) Achieving the Paris Climate Agreement Goals. |

|

Hvid Horup, L., Ohms, P.K., Hauschild, M., Gummidi, S.R.B., Secher, A.Q., Thuesen, C. and Ryberg, M. (2024) |

Evaluating mitigation strategies for building stocks against absolute climate targets. Buildings and Cities, 5(1), p. 117–132. |

|

UKGBC |

|

|

Reduction roadmap 2.0 (Denmark) |

|

|

Australian reduction roadmap |

|

|

Türkiye Building Sector Decarbonization Roadmap |

Considering planetary boundaries, ideally, both targets and mitigation pathways should account for direct, indirect and embodied GHG emissions (including F-gases). In terms of developing detailed agendas and goals, it is recommended to divide the built environment into residential, non-residential (commercial and institutional) and infrastructure and to distinguish between new construction and refurbishment. National statistics should be supplemented accordingly, including a cross-sectoral approach and the territorial and polluter pays principle. In the development and updating of mitigation roadmaps, the trends/scenarios for climate change, user and broader stakeholder behaviour, demand for built areas, decarbonisation of energy supply, decarbonisation of construction product manufacture, amongst others, need to be considered.

A target year for achieving a balanced situation for GHG emissions, caused by GHG emissions from BCR sector can either be defined politically or determined on the basis of a remaining carbon budget and a forecast for its depletion and interim progress targets towards this goal (i.e. reduction in terms of a percentage or absolute figures at specified years).

Advocacy and a call to action

Without a BCR sector-specific mitigation target and reduction pathway, stakeholders' role may be unclear, mitigation efforts may be disorganised and not harmonised, and implementation may have little or no effective governance mechanism or system (Wang et al. 2014).

With a clearly defined mitigation goal and pathway - even if rudimentary or at basic level only for some countries - this would:

- serve as a strategic guide for government and industry

- provide an action plan for industry to meet the NDC pledge

- serve as a chapter in national GHG and/or sustainability reporting

- provide a step-by-step approach and timetable for tightening, over time, the (legal) requirements for limiting GHG emissions in the life cycle of buildings.

We repeat our pre-COP29 call for a stronger collaboration between researchers and policymakers (Foliente et al. 2024; Kuittinen et al. 2024) to support the recommendations herein. The IEA EBC Annex 89 sub-task leaders, teams and participants from 21 countries are currently working to develop implementation guidance and aids for policies and measures for net-zero, whole life carbon building, construction and real estate.

Every year and every COP that countries delay action make the emissions reduction challenge harder to achieve. The upcoming COP is the right time to make the next step. UNFCCC Parties and countries should set their NDC3.0 to include a specific goal for BCR sector, supported by a national mitigation strategy.

References

BBSR. (2020). Umweltfußabdruck von Gebäuden in Deutschland. BBSR-Online-Publikation 17/2020. https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/veroeffentlichungen/bbsr-online/2020/bbsr-online-17-2020-dl.html?v=3&__blob=publication-File

Buildings and Climate Global Forum. (2024). Ministerial Declaration. https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/documents/DECLARATION%20DE%20CHAILLOT-NP.pdf

EU. (2024). Directive (EU) 2024/1275 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 April 2024 on the energy performance of buildings (recast). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1275/oj/eng

Foliente, G., Lützkendorf, T. & Kuittinen, M. (2024). Researchers' call to action for breakthrough decarbonisation policies in the building sector. https://sbe-series.org/climate-action/

GlobalABC. (2016). Global Status Report - Towards zero-emission, efficient and resilient buildings. https://globalabc.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/GABC_GSR_2016.pdf

GlobalABC. (2025). Buildings Breakthrough Priority International Action. https://globalabc.org/buildings-breakthrough

Kuittinen, M., Lützkendorf, T. & Foliente, G. (2024). Net-zero requires improved collaboration between researchers and policymakers. [commentary]. Buildings & Cities. https://www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/researchers-climate-policy-gaps.html

Reddy, S., Sarraf S. & Kapoor, R. (2024). NDCs for Buildings: Ambitious, Investable, Actionable, and Inclusive - Guidance for Policymakers and Practitioners in the 2025 NDC revision. Paris: Partnership for Energy Efficiency in Buildings (PEEB) Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction (GlobalABC) and Intel Nations Environment Programme (UNEOP. https://globalabc.org/resources/publications/ndcs-buildings-ambitious-investable-actionable-and-inclusive

Wang, T., Foliente, G., Song, X., Xue, J. and Fang, D. (2014). Implications and future direction of greenhouse gas emission mitigation policies in the building sector of China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 31, 520-530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.12.023

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.