www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/reviews/experiential-design-schemas.html

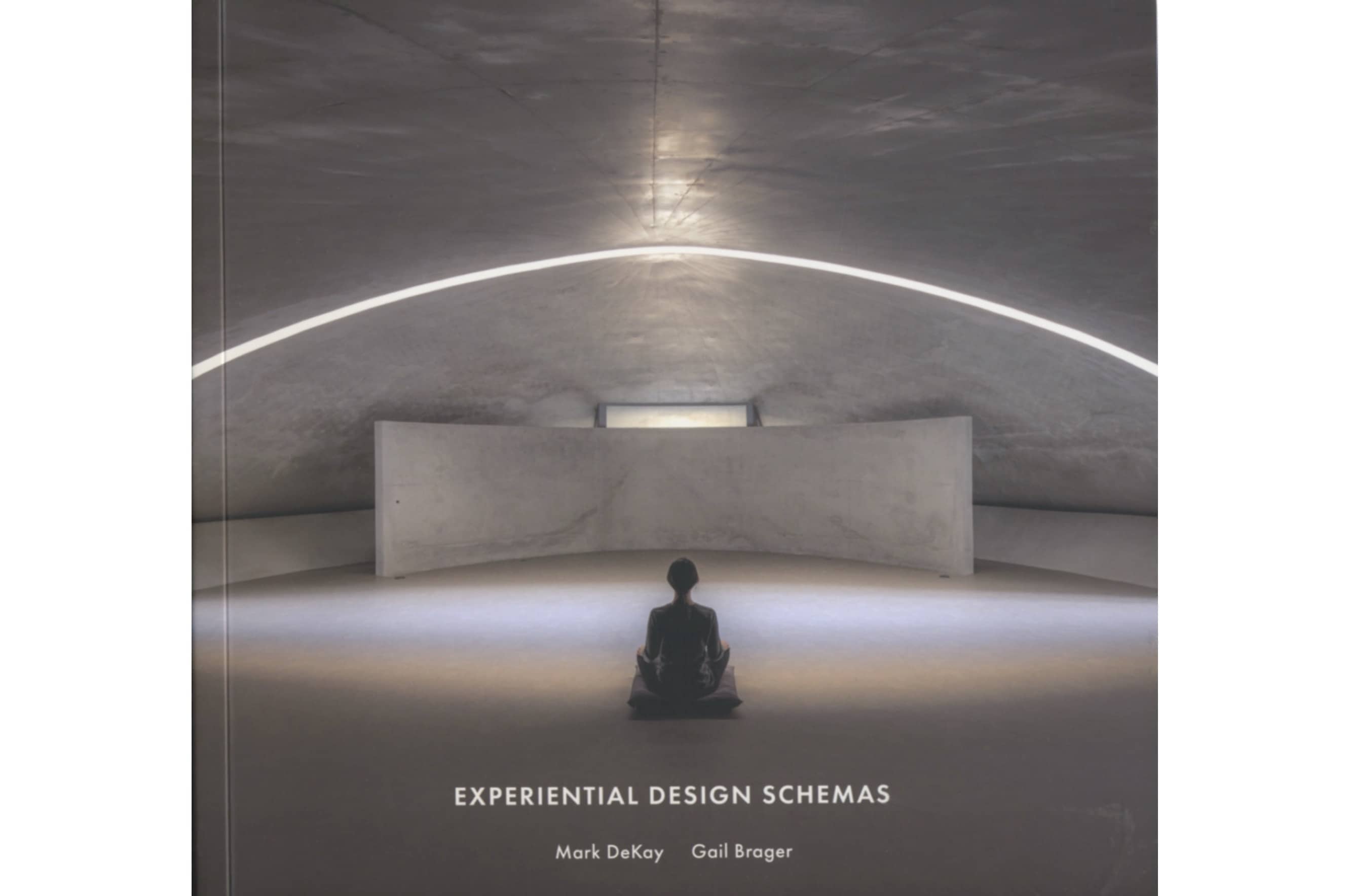

Experiential Design Schemas

By Mark DeKay and Gail Brager. Oro Editions, 2023, ISBN: 9781957183732

Dean Hawkes (Emeritus Professor, Welsh School of Architecture and Emeritus Fellow, Darwin College, Cambridge) welcomes this valuable resource for thinking about the many experiential dimensions of architecture.

In the early 1960s, as I was completing my architectural education, I had the good fortune to encounter Steen Eiler Rasmussen's wonderful book, Experiencing Architecture (1962). Shortly afterwards I joined the Department of Architecture at Cambridge as a junior researcher on daylight in buildings and, in 1965, I attended my first academic conference where I met Victor Olgyay, the Hungarian/American architectural environmentalist. As a result, bought my copy of his seminal book, Design with Climate (1963) . Together these books became the foundations of the life I have led for six decades as a scholar, teacher and practitioner of environmental design in architecture. With his appeal to the experience of our human senses Rasmussen may be said to represent the poetics of the architectural environment whereas Olgyay, with his focus on 'analytical reasoning', is the representative of the realm of technics.

This polarity of poetics and technics defines, in broad terms, the scope addressed by this substantial new book by Mark DeKay and Gail Brager, architect and building scientist respectively. In the preface DeKay quotes from Luis Barragán's lyrical statement in his 1980 Pritzker Prize acceptance speech:

'It is alarming that publications devoted to architecture have banished from their pages the words Beauty, Inspiration, Magic, Spellbound, Enchantment, as well as the concepts of Serenity, Silence, Intimacy and Amazement. All these have nestled in my soul, and though I am fully aware that I have not done them complete justice in my work, they have never ceased to be my guiding light.'

From here the objective of the book is announced:

'In exploring the terrain of experiencing architecture, our work in this book is to both expand the realm of delight-beyond-comfort and to venture into the peaks and potentials of human experience that guided Barragán, to which we might only add the felt sense of connecting to Nature. In providing some conceptual scaffolding and, we hope, some practical tools, our overall intention is to catalyze design that joyfully connects people to nature.'

The instrument for the realisation of this objective is the idea of the Experiential Design Schema, which is defined as:

'a narrative/graphic generative design aid that helps designers find and employ experiential concepts. As defined in this work, a schema is the organization of form and space that disposes environmental conditions to create a field of potential positive human experiences.'

The theoretical basis of the schemas is explained in three chapters with the titles, 'Beyond Comfort', 'Integral Experience' and 'Excited by Evidence'. The first presents a critique of what one might describe as the current orthodoxy of environmental design theory and practice. Amongst the extensive references we find the work of Judith Heerwagen on biophilia and sensory aesthetics (e.g. Heerwagen & Gregory 2008), Lisa Heschong on Thermal Delight in Architecture (1979), Ralph Knowles, Sun, Rhythm, Form (1981), Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses (1996) and Jun'ichiro Tanazaki, In Praise of Shadows (1977). These are completed by a selection of well-chosen images of buildings by architects as diverse and relevant as Bernard Tschumi, Francis Keré, Le Corbusier and Grafton Architects that help give expression to the abstractions of theory.

'Integral Experience' is an attempt to 'explain' the ways in which we experience buildings. Once again 'theory', is illustrated by reference to specific buildings; the first, Peter Zumthor's Therme Vals, the second, Sverre Fehn's Nordic Pavilion in Venice, third. Lopez Salgado's Stamp Museum at Oaxaca, Mexico and, finally, Frank Lloyd Wright's Edwin Cheney House in Oak Park. These are complemented by reference to the idea of 'archetypes', illustrated by the 'Vocabulary of architypes in architecture' proposed by Thiis-Evensen in 1987. These become the background of a four-part diagram - 'quadrants' - that presents 'The integral context of architectural experience', respectively: Behavioural Perspective, Systems Perspective, Experiences Perspective and Cultures Perspective. This is accompanied by a key statement:

'The core of this book is the experiential design schemas in Chapter 4, design guidance that begins with experiential intentions, which we then relate to actionable means to accomplish them via built form and related design disciplines.'

The third of these 'theoretical' chapters, 'Excited by Evidence', turns to the matter of the 'sensescape', the visual, thermal, acoustic and olfactory components of environments as these are experienced, individually and in combination, by the human senses. Key themes include the value of variability of environments, adaptive opportunity and a succinct summary of the physiological basis of vision in which the significance of the circadian cycle is highlighted. An interesting passage on the Adaptive Comfort Model of thermal design brings a reminder of Olgyay's pioneering work with a map of the United States showing regional differences in comfort across the climate zones of the continent. Olgyay's subtitle was ''Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism'. Explorations of 'soundscapes' and the 'olfactory environment' complete this useful chapter.

In Chapter 4 we reach the substance of the

book with a detailed presentation - a cataloguing, of no less than 53 Experiential

Design Schemas. These are summarised on

a matrix with axes labelled 'Distribution of Conditions' and 'Levels of Scale

and Complexity'. The first identifies

the following:

C: Contrast, G : Gradient, R: Rhythm, F: Flux, S: Sequence, N: Narrative

followed by:

1: Materials, 2:

Elements, 3: Building Systems, 4:

Rooms, 5: Room Organizations, 6: Whole Buildings

The 'Anatomy' of each Schema is presented graphically over four pages, beginning with 'precedents' followed by 'supporting evidence', 'design guidelines' and a 'navigational system'. The precedents consist of images and commentaries of one or two buildings, usually from current practice, that in some way are considered to represent the focus of the given schema. For example, schema C2, 'Haptic Connection', is illustrated by an image of the heated brick cill that runs beneath the windows of the cloister at Aalto's Saynatsalo Town Hall, the leather wrapped door handle of the Villa Mairea and an elegant metal handrail in the Museu Brasileira da Escultura e Ecologia in Sao Paolo by Paulo Mendez da Rocha. The 'supporting evidence' is in each case, a summary of relevant objective information, in the case of C2 this includes an interesting study of human interactions with the thermal environment. The 'design guidelines' outline the circumstances in which 'Haptic Connection' is a relevant consideration. A novel element of each 'schema' is the inclusion of a haiku, written by DeKay. These are intended to, 'concretize some aspect of what is presented in the design schema … to set a tone as both pedagogical and performative metaphor.'

The haiku that accompanies schema C2, with its Aalto precedents reads:

a warm brumal hearth

a cool rail in canicule

delighted the hand

In the concluding chapter we read:

'This book emphasizes creating fields of experiential possibilities in buildings that provide greater variety and options by designing environmental condition more dynamic and spatially non-uniform than found in common design approaches.'

In the 21st century environmental design has moved to the centre ground of the theory and practice of architecture. The pressures of climate change are redefining our relationship with nature, with profound implications for how we conceive and inhabit our buildings, and, in a direct line of descent from Rasmussen, the experiential dimension has gained greater force in the writings of Heschong, Pallasmaa, referred to above, with, among many more recent contributions, books by Zumthor, in his lyrical Atmospheres (2006), Griffero, Atmospheres: Aesthetics of Emotional Space (2016), Böhme, The Aesthetics of Atmospheres (2017) and my The Environmental Imagination (2008 & 2018).

In Experiential Design Schemas Mark DeKay and Gail Brager have drawn together an encyclopaedic volume of material in an attempt to produce a tool for design that encompasses environmental design in all its dimensions, from technics to poetics. In its intentions and elements this is a noble project and the book stands as a valuable reference source. However, I am unconvinced by the proposition that the design of a building, of any purpose or scale, may be realised by following such a systematic procedure of schematic reference. I firmly believe that the design of even a simple building is a complex matter that demands careful thought of its many dimensions. But the answer will not come from a rote process of analysis and addition, but from the discovery - or 'dis-covery' as Peter Zumthor puts it - of some definable question - or questions - that arise from the unique circumstances of the project. All else follows from this. It is here where acts of invention and imagination come into play, as they were called upon by all of those architects whose works illustrate and inform this book.

References

Böhme, G. (2017). The Aesthetics of Atmospheres. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN: 9781315538181

Griffero, T. (2016). Atmospheres: Aesthetics of Emotional Spaces. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN: 9781315568287

Hawkes, D. (2008, second edition 2018). The Environmental Imagination: Technics and Poetics of the Architectural Environment. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-62898-4

Heerwagen, J.H. & Gregory, B. (2008). Biophilia and sensory aesthetics. In S.R. Kellert, J.H. Heerwagen & M. Mador (eds.) Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Chichester: Wiley. ISBN: 9780470163344.

Heschong, L. (1979) Thermal Delight in Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN: 9780262580397

Knowles, R. (1981). Sun, Rhythm, Form. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN: 9780262110785

Olgyay, V. (1963). Design with Climate: Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Pallasmaa, J. (1996). The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN: 9781119943501

Rasmussen, S.E. (1962). Experiencing Architecture. (1962). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tanazaki, Jun'ichiro. (1977). In Praise of Shadows. Sedgwick, ME: Lete's Island Books. ISBN: 9780918172020

Zumthor, P. (2006). Atmospheres: Architectural Environments, Surrounding Objects. Basel: Birkhäuser. ISBN: 9783764374952

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Living labs as ‘agents for change’ [editorial]

N Antaki, D Petrescu & V Marin

Post-disaster reconstruction: infill housing prototypes for Kathmandu

J Bolchover & K Mundle

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.