www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/reviews/designing_neuroinclusive_workplace.html

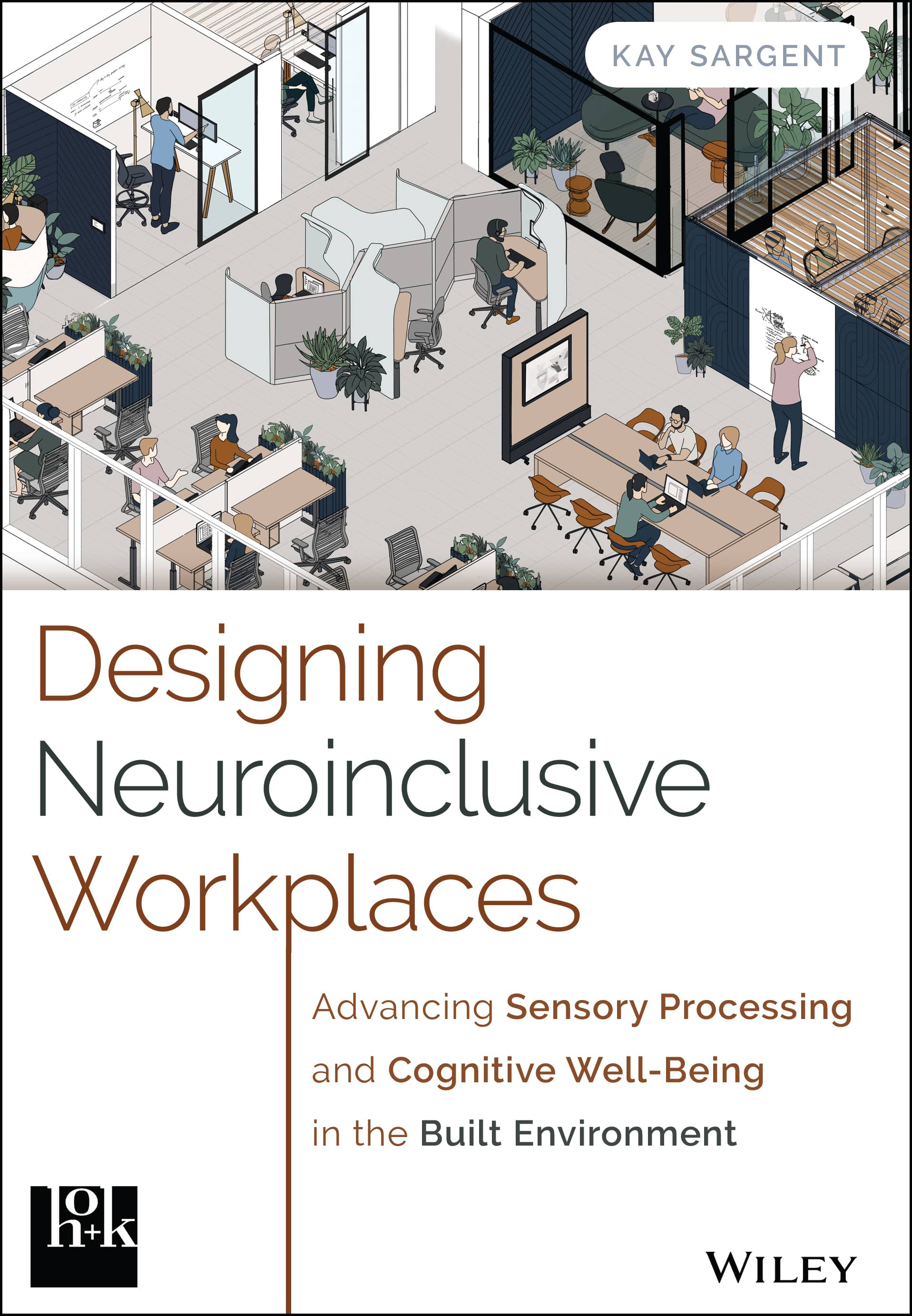

Designing Neuroinclusive Workplaces

By Kay Sargent. John Wiley & Sons, 2025, ISBN: 1394309337

Kerstin Sailer commends this book, as it fills an important gap for scholars, the design community and the workplace community. It provides understanding on how people with different sensory profiles can thrive in the work environment and insights for creating inclusive workplaces.

The built environment does not present itself in the same way to all people. Perceptions of buildings and spaces vary, yet design all too often assumes an average person as user and therefore might fail to accommodate people with distinct sensory profiles.

Taking up the challenge to understand how to design for neuroinclusion, this book takes the readers on a journey to explore what neurodivergence means; how it presents itself as a series of dynamic preferences for certain spaces and settings; and what designers of workplace environments should consider in order to create inclusive solutions that work for everyone.

Neurodivergence affects around 20% of the population and includes distinct diagnoses such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, Asperger’s, dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, dyspraxia, Tourette’s syndrome, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and synesthesia. Some workplaces may find that closer to 50% of their workforce are affected; for example in research-intensive industries, with many people never having received a formal diagnosis. Sargent explains that sensory profiles can be 'spiky', i.e. pronounced in some areas and not in others. An important distinction is made between hypersensitivity (seeking to reduce stimulation) and hyposensitivity (seeking out stimulation).

The built environment plays a significant role in mediating the sensory processing capacities of people:

'What might be merely annoying to neurotypicals could be debilitating to neurodivergents.' (p. 11)

But how would you, for example, design for someone with ADHD?

This seemingly innocent question posed to the author in 2016 marked the beginning of almost a decade of work, culminating eventually in the publication of this much needed book. At the time, little research or guidance existed on how to design workplaces for people with sensory differences and this persistent dedication to the topic possibly constitutes the biggest contribution made by Sargent: to raise awareness, to summarise what we know about neurodivergent characteristics, to apply this to workplace design principles, and thus to make it accessible to designers.

An academic literature search on neurodivergence in workplace design reveals less than a dozen texts, all published in the last two years. This highlights the foresight and pioneering nature of Sargent’s contribution.

The book tells the author’s story across fifteen, mostly short chapters that build on each other but can also be appreciated as standalone texts. For instance, business leaders who need convincing that designing for an apparent minority makes business sense will find chapter 3 relevant. Designers interested in concrete procedural advice can delve into chapter 12, which details a step-by-step process to follow for neuroinclusive design. It covers many actions to take before the actual design begins, including: consultation with professionals, education of design teams, an audit of existing client spaces, ensuring leadership buy-in and conducting employee interviews.

Chapter 13 provides a concrete design approach and zoning strategy for workplace environments that builds on activity-based working principles, whereby employees have choices of different settings to conduct their activities. This approach will be known to many workplace designers and strategists, but what is different here is a clear articulation of how to maximise diversity, flexibility and choice. For instance, not everyone will enjoy shifting positions regularly. For autistic individuals, a routine is key, so it should be possible for people to choose the exact same location every day. Context is also considered much more systematically than usual, so what is placed next to what can turn a space from overwhelming to accommodating. For example, rest spaces hidden away and only reachable via a loud and noisy corridor will not work well; likewise, rest spaces with overstimulating colours or materials might work for hyposensitive individuals but not for those with hypersensitivities. Examples are provided of many different floor plans and detailed diagrammatic drawings of neighbourhoods and zones that offer maximum choice for six different work modalities (concentrate, contemplate, communal, create, congregate, and convivial) and for both neurotypes (hypo- and hypersensitive).

The text presents itself as easily readable and is interspersed with personal stories, spotlight interviews with key stakeholders and profiles of important personalities in business and culture who convey neurodivergent traits, adding nuance and interest to the discussion.

The book will appeal to a variety of readers, yet in differentiated ways. The main anticipated audience – designers and architects – will appreciate the clear writing, design diagrams and concrete suggestions. Every designer and architect wishing to create more inclusive spaces should read the book. It is high time books like this were added to the curriculum of architecture schools to raise awareness for issues of inclusivity, how to design differently, and how to integrate user needs and preferences more systematically.

Organisations and HR professionals will find it interesting to consider how the design of spaces relates to organisational and operational issues. Inclusive hiring policies for instance will not achieve their results, if workspaces are designed in a way that make it impossible for people with different sensory profiles to succeed and perform well.

Individuals with neurodivergent traits can use the book to understand their own intuitive preferences better. Realising how design impacts your performance and well-being can be empowering and help affect change in workplaces.

For academic audiences, the book might be less compelling as some discussions lack the necessary depth scholars seek, although arguably they might not be the main anticipated readership. The book does not connect with the longer tradition of disability studies in architecture and design, with some contributions reaching back to the 1980s and 1990s (Hall & Imrie 1999) and a flourishing discussion emerging in the mid-2010s (Boys 2014; 2017). A lot of these contributions include invisible disabilities such as neurodivergence, and some select pieces (Cassidy 2018) as well as a recently published edited book (Illes et al. 2022) explicitly bring it in as a main focus. The relevant social model of disability, which maintains that individuals are not disabled because of their bodies but because the environment is disabling them is only mentioned briefly almost towards the end of the book. In my view, it would have deserved a more prominent place in the overall framing of neurodivergence as a disability.

Nonetheless, this book is an invaluable contribution providing useful information and practical advice to both the design community and the workplace community. It deserves wide acclaim. Given the dearth of rigorous research on the topic, the book fills an important gap for scholars of the workplace and can be seen as a major contribution that raises relevant further research questions to explore.

References

Boys, J. (2014). Doing disability differently: An alternative handbook on architecture, dis/ability and designing for everyday life. Routledge.

Boys, J. (2017). Disability, space, architecture. Taylor & Francis.

Cassidy, M.K. (2018). Neurodiversity in the workplace: Architecture for autism (Master's thesis, University of Cincinnati).

Hall, P. & Imrie, R. (1999). Architectural practices and disabling design in the built environment. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 26(3), 409-425.

Illes, J., Clarke, A., Boys, J. & Gardner, J. (2022). Neurodivergence and architecture (Vol. 5). Academic Press.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.