www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/self-organised-living-lab.html

Self-Organised Knowledge Space as a Living Lab

How can a self-organised initiative in an informal settlement foster community engagement and confront social issues?

While Living Labs are often framed as structured, institutionalised spaces for innovation, Sadia Sharmin (Habitat Forum Berlin) reinterprets the concept through the lens of grassroots urban practices. She argues that self-organised knowledge spaces can function as Living Labs by fostering situated learning, collective agency, and community resilience. The example of a Living Lab in Bangladesh provides a model pathway to civic participation and spatial justice.

Grassroots innovation

In practice, Living Labs are typically project-driven initiatives led by institutions, municipalities, corporations, or academic bodies to test innovations in areas such as urban development, sustainability, or technology. While often participatory, these initiatives are rarely initiated from within marginalised communities. For grassroots groups—frequently excluded from planning and decision-making processes—the Living Lab concept remains elusive, as they often lack access to formal frameworks, resources, or institutional partnerships. Consequently, their efforts are usually framed as “community-driven development” or “informal urban practices” rather than recognised as Living Labs. Yet, many of these initiatives embody similar principles: user-centered co-creation, real-life experimentation, multi-stakeholder collaboration, and iterative innovation in open, real-world settings.

This article explores one such example from an informal settlement in Bangladesh, where a self-organised knowledge space—emerging from within the community—functions as an experimental ground where alternative pedagogies and spatial justice are co-produced.

Spanning over 190,000 m2, Karail Basti is the largest self-organised neighbourhood in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, and home to nearly 120,000 people. Over the past three decades, it has been shaped by the collective labor, entrepreneurial spirit, and unwavering resilience of its residents (Bertuzzo 2016). Despite precarious tenure, inadequate infrastructure, and systemic exclusion, Karail today stands as a vibrant hub for grassroots organisations and community-led initiatives. Among them is the Shaheed Rumi Memorial Library—an unlikely space of care, learning, and civic engagement that quietly took root in 2014. Though called a library—mainly due to its emphasis on collective reading and to establish a recognisable identity within the neighbourhood—Rumi Library has, over the past decade, evolved into a politically conscious social organisation that extends far beyond the conventional idea of a library.

A self-organised knowledge space

The emergence of the Rumi Library in Karail is rooted in a convergence of individual agency for change, a collective desire among children and young people in Karail to read and learn together through practice, and a stark absence of care infrastructures within the neighbourhood.

The library’s founder, Rafsanul Ahsan Sazzad, first arrived in Karail in 2008 as a teacher in an NGO-funded education program for children. During the few years the program operated, he developed a deeper understanding of the everyday struggles in the settlement—especially those affecting children's access to meaningful and consistent education. Most NGO-led initiatives were short-lived, functioning more as delivery mechanisms than as long-term engagements, with little follow-up or sustained mentorship.

In a neighbourhood like Karail, where most available services have to address emergency needs (e.g. housing, water, electricity, sanitation, and basic schooling), the emotional, psychological, and intellectual dimensions of children’s lives remained largely unacknowledged. Adolescents navigating the complex terrain of changing bodies, shifting identities, and social expectations had no mentor and safe space to ask questions, seek academic or emotional support, or simply speak freely. Sazzad was, however, driven by a belief that social transformation does not have to wait for a revolution. Amid widespread frustration with the performative nature of many political and institutional actors, he began to question himself: What can an individual do, here and now, to make a difference?

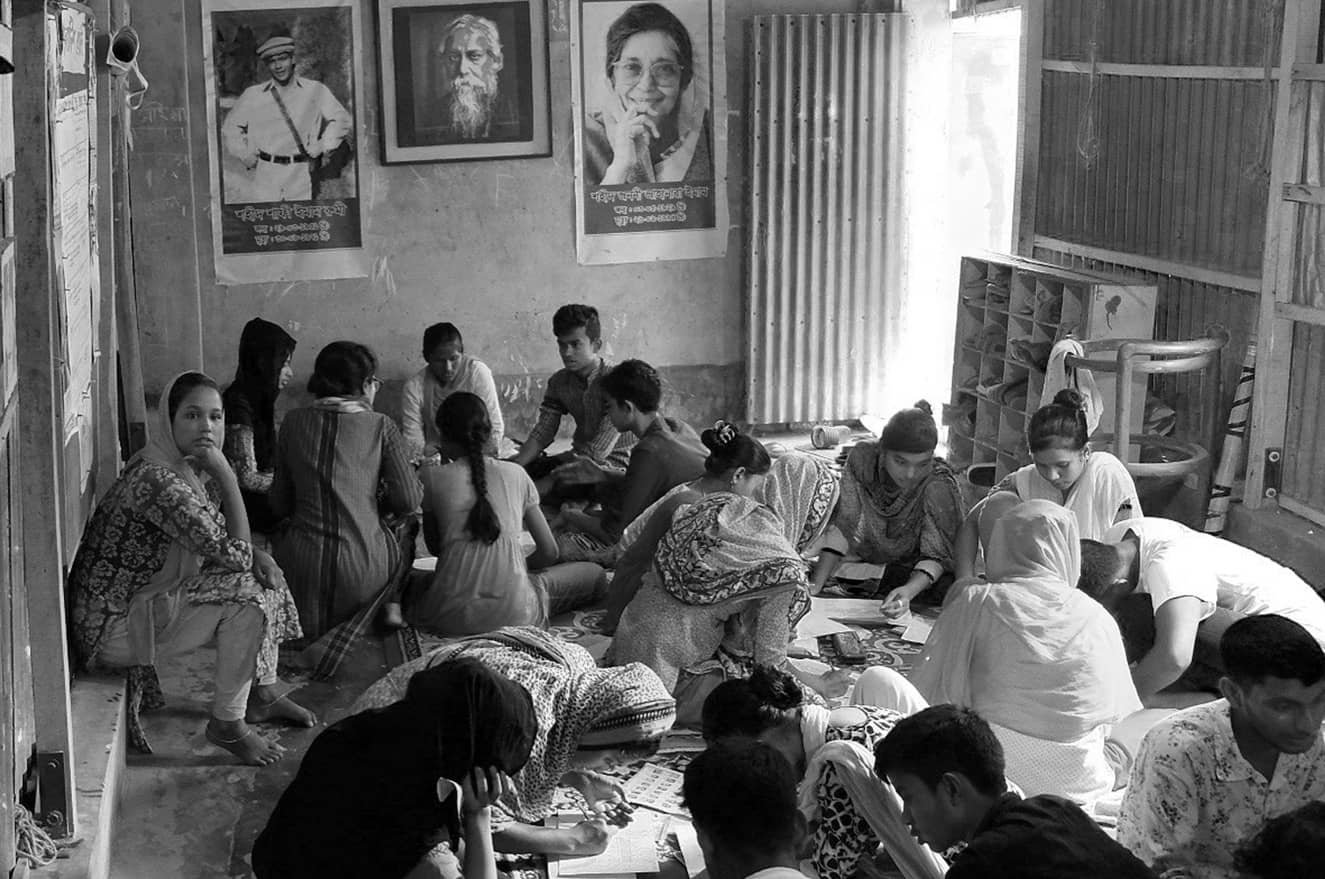

His answer came in the form of action—modest in scale, yet transformative in intent. The Rumi Library was born on 1 October 2014, in a rented room made of corrugated iron sheets in Karail, with only seven members. The self-organised learning space—initially just a few books, a handful of children, and one adult willing to listen—has become a microcosm of co-created knowledge and mutual care. Over the past ten years, it has evolved into a localised form of Living Lab—not in the traditional academic-industrial sense, but as a real-life civic innovation ecosystem, grounded in the everyday experiences, aspirations, and struggles of its users.

Building trust and community

The early days of the Rumi Library were marked by both hope and resistance. Creating a space where girls and boys could read and learn together challenged deeply entrenched gender norms and social expectations in Karail. Some parents questioned the participation of girls, citing concerns rooted in religious and cultural prejudices. Others were sceptical about the idea of a “library” operating outside the boundaries of formal education or religious instruction.

Establishing a free and open-minded space for young people—where initiatives are run and led by its members—posed a challenge to many existing power structures within the neighbourhood, particularly those backed by political parties. The library had to engage in creative and resilient negotiations to claim its position within the settlement while remaining independent of NGO and political affiliations.

Resource constraints pose another significant challenge. The library is sustained through membership fees, which are individualised based on each member’s capacity. Yet these contributions barely cover the rent for the small, tin-roofed room. Basic needs like books, computer, drawing materials, and furniture are met through the generosity of friends and well-wishers. Even so, sustaining the space require constant coordination, creativity, and solidarity.

Beyond infrastructure, the library also has to confront social issues directly affecting its young members. Child marriage remains a pressing concern, especially for girls who show promise in their studies but are forced to drop out due to family pressure. Many boys struggle with the influence of negative peer groups and the lure of harmful habits. In response, the library emphasises not only reading and academic support but also advocacy, mentorship, life skills, and emotional resilience.

While these challenges continue to affect the everyday life in Karail, the Rumi Library actively engages with them—navigating, responding to, and resisting these pressures through its ongoing, grounded practices.

Ripples within and beyond

The Rumi Library fosters youth mentorship and community leadership by creating a space where learning is rooted in reflection, care, and critical engagement. What begins with simple reading circles evolves into meaningful conversations—discussing literature, novels, and diverse narratives of struggle and resistance. The members engage with the lives and works of inspiring leaders, poets, activists, and scientists, drawing lessons about injustice and power of taking action. These discussions often expand into deeply personal territories—navigating emotional dilemmas, relationships, questions of love, friendship, and responsibilities as citizens.

Cultural programs—both within and beyond Karail—form another vital part of the library's ecosystem. From celebrating International Mother Language Day to Bengali New Year and Eid festivals, these events are imagined, planned, and performed entirely by the young members. Through this hands-on experience, youth learn teamwork and public engagement. Senior members mentor younger participants, ensuring that leadership is constantly practiced, passed on, and renewed.

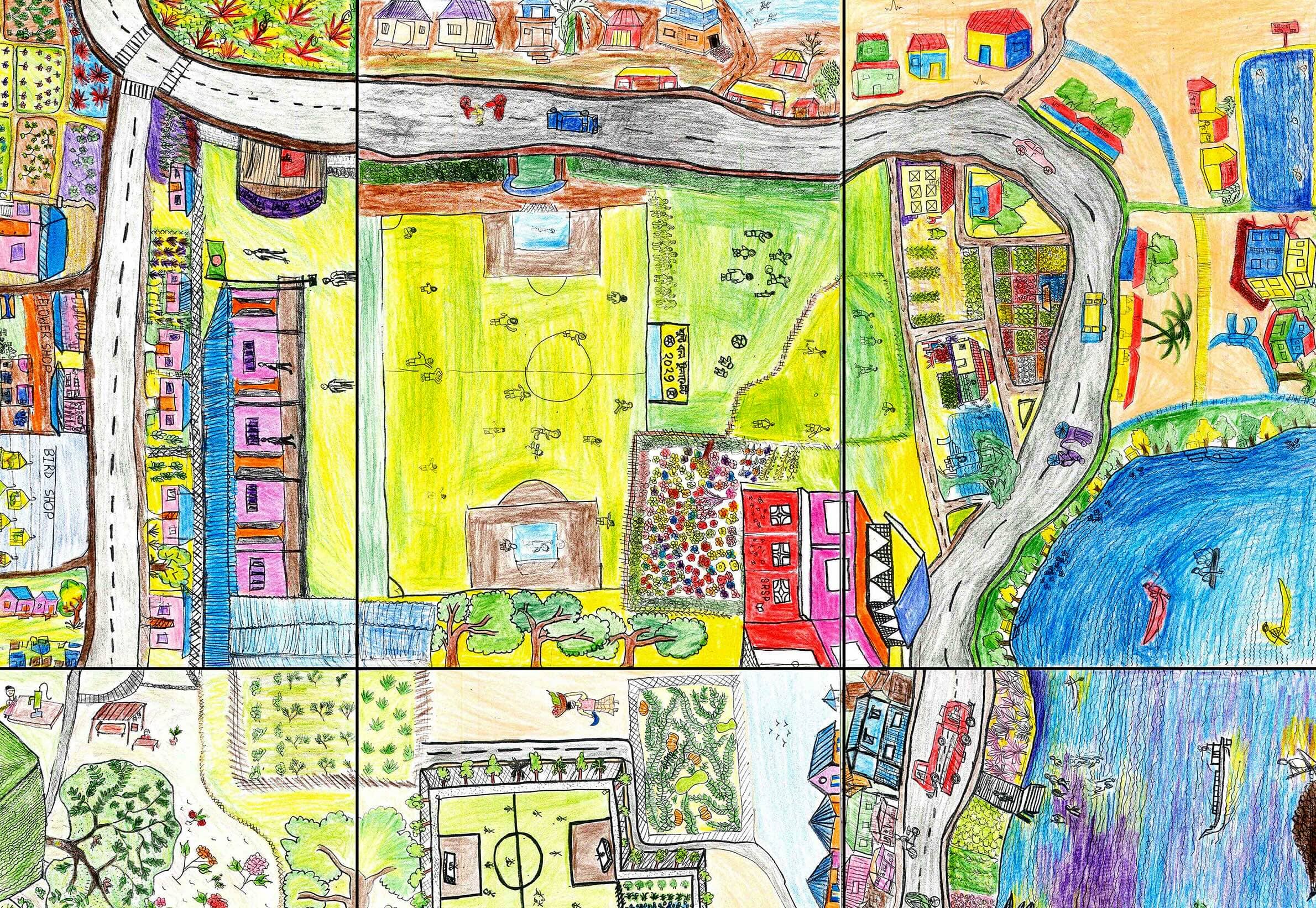

Over

the years, it becomes a hub for collaboration. Educators, spatial

practitioners, artists, and researchers voluntarily join hands with library

members. One such long-term collaboration involves participatory action

research with a spatial practitioner, where children and teenagers map their

daily experiences in the neighbourhood and future vision for Karail through

drawing and audio-visual narratives. This process not only sharpens their

critical thinking about the built environment but also introduces them to practice-based

and qualitative research aimed at sustainable community development.

Library

members actively engage in civic life by initiating small-scale, self-organised

projects rooted in creative advocacy and storytelling. One powerful example is the creation of a

graphic novel based on real-life experiences of girls in Karail. This visual

narrative becomes a tool to open dialogue around gender-based violence—bringing

sensitive, often-silenced issues into community conversation. Members have also

organised protests and demonstrations in Karail and nearby areas to raise their

voices against gender violence, child abuse, and to demand housing rights for

the urban poor. These initiatives

reflect a deep culture of solidarity, collective responsibility, and political

awareness rather than charity.

The long-term impact of the Rumi Library is evident in the continued engagement of its youth members. When NGOs or pilot projects enter Karail, it is often library-trained youth who step in with the experience, sensitivity, and leadership required to support them. The co-learning and mentorship culture of the library nurtures a new generation of community changemakers—young people who contribute with confidence, skill, and a deep understanding of their context.

Conclusion

Rumi Library in Karail is not a blueprint—but it is a prototype. Its strength lies not in scalability by replication, but in adaptability by principle: the principle that education is not just content delivery, but an ethical and spatial commitment to listening, supporting, and growing together.

In the context of Karail, the emergence of the self-organised library is not only an act of individual agency, but also a quiet form of resistance—a challenge to dominant development models that reduce education to short-term service delivery or awareness campaigns. Instead, the Rumi Library proposes a different logic: one of continuous, evolving, and community-rooted learning that nurtures curiosity, trust, and mutual responsibility.

This is not a library in the conventional sense. It is a relational space where knowledge is co-created—where teenagers come not just with homework questions, but with reflections on life, politics, love, fear, injustice, and aspiration. Books serve as entry points to deeper conversations, which grow into meaningful bonds. Mentorship unfolds organically, not through programs, but through sustained presence, listening, and mutual recognition. Over time, the space becomes a practice of situated learning—where knowledge and meaning emerge from lived experience, and where education is inseparable from ethics, care, and community.

Crucially, this initiative challenges the spatial and political invisibility of Karail itself. In a settlement excluded from urban planning and denied legal recognition, the library becomes a quiet but firm assertion of urban citizenship. It says that the youth of Karail, too, are entitled to spaces of care, dialogue, and education—not as acts of charity, but as civic rights.

In carving out space where none existed, Rumi Library operates as a community-centered living lab—testing ways of learning, relating, and resisting in conditions of precarity. It does not aim to replicate formal institutions, but to transform the very terms through which knowledge, belonging, and participation are imagined. It shows how communities of practice can emerge from the margins, turning everyday life into a terrain for civic imagination and spatial justice.

Reference

Bertuzzo, E. T. (2016).On the myth of informal urbanisation: Karail Basti, Dhaka. ARCH+, (223), 110–117. https://www.academia.edu/30889521/ENGL_On_the_myth_of_informal_urbanisation_DT_Zum_Mythos_der_informellen_Urbanisierung

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.