www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/reducing-concrete.html

How R&D is Reducing the Use of Concrete

Concrete has high environmental impacts. Can the construction industry reduce the volume of concrete that is used?

After water, concrete is the most widely used substance on earth. Paul Shepherd (University of Bath) explains how deep reductions in the amount of concrete used in buildings can be achieved through advanced structural design and fabrication.

Concrete is an easy target. It responsible for around 8% of the UK's anthropogenic carbon emissions (Lehne 2018, p1), as well as being a significant contributor to the world shortage of sand as a raw material (UNEP 2022). Its climate and environmental impacts are very high and damaging. However, concrete is a very useful material and is ubiquitous in modern construction. It starts life as a liquid, which means it can easily be moulded into complex shapes, and it is very efficient at resisting compressive forces. However, the way concrete is currently used in construction is incredibly wasteful. This is due to the high cost of labour which has led to the design and construction of buildings being focused on ease of construction, standard components and reduced labour. The frugal issue of materials was a historical issue, but this does not figure in the economics of modern construction practice.

A key challenge is whether and how to use less concrete. Researchers at the Universities of Bath, Cambridge and Dundee in the Automating Concrete Production (ACORN) project are developing a new approach to the structural design and fabrication of concrete components. The emphasis is developing highly efficient shapes for concrete beams, columns, floor slabs, etc. that place material where it is most needed for compression. This results in more complex shapes, but significantly less concrete is required. Their main focus to-date has been on commercial and office buildings, where concrete is often used to produce floors on regular grids with 6-12 m spans, generally in combination with raised floors. However, their philosophy of using less concrete by being careful where it is used would be equally beneficial to residential housing, schools and all types of high-rise. The ACORN project was funded through UKRI's 'Transforming Construction Challenge' to achieve the 'Construction 2025 Strategy' targets of increasing project delivery speed and productivity whilst slashing whole-life costs and carbon emissions.

If the shape of a beam can be changed, such that the load is supported by an arch, or the shape of a floor changed to support load with a vaulted shell, then the material can be used as it wants to be, in compression, and needs no steel reinforcement.

ACORN's response was to find innovative ways to fabricate these complex shapes and to overcome the 'harder to make' argument. Part of the solution is to harness the computing power and robotics to automate the process. This in turn implies that the concrete components will need to be made off-site in a factory-like setting (or possibly in a temporary factory installed near-site). Far from being a disadvantage, the move to off-site can bring more consistency, better quality control, improved health and safety and a higher-skilled workforce. Admittedly this does put an upper limit on size of element that can be made in one piece and still transported to site. But the move towards a kit of parts designed for easy assembly on-site can not only make drastic cuts to erection times but also allows parts to be disassembled and reused on refurbishments or new-builds elsewhere, promoting a circular economy.

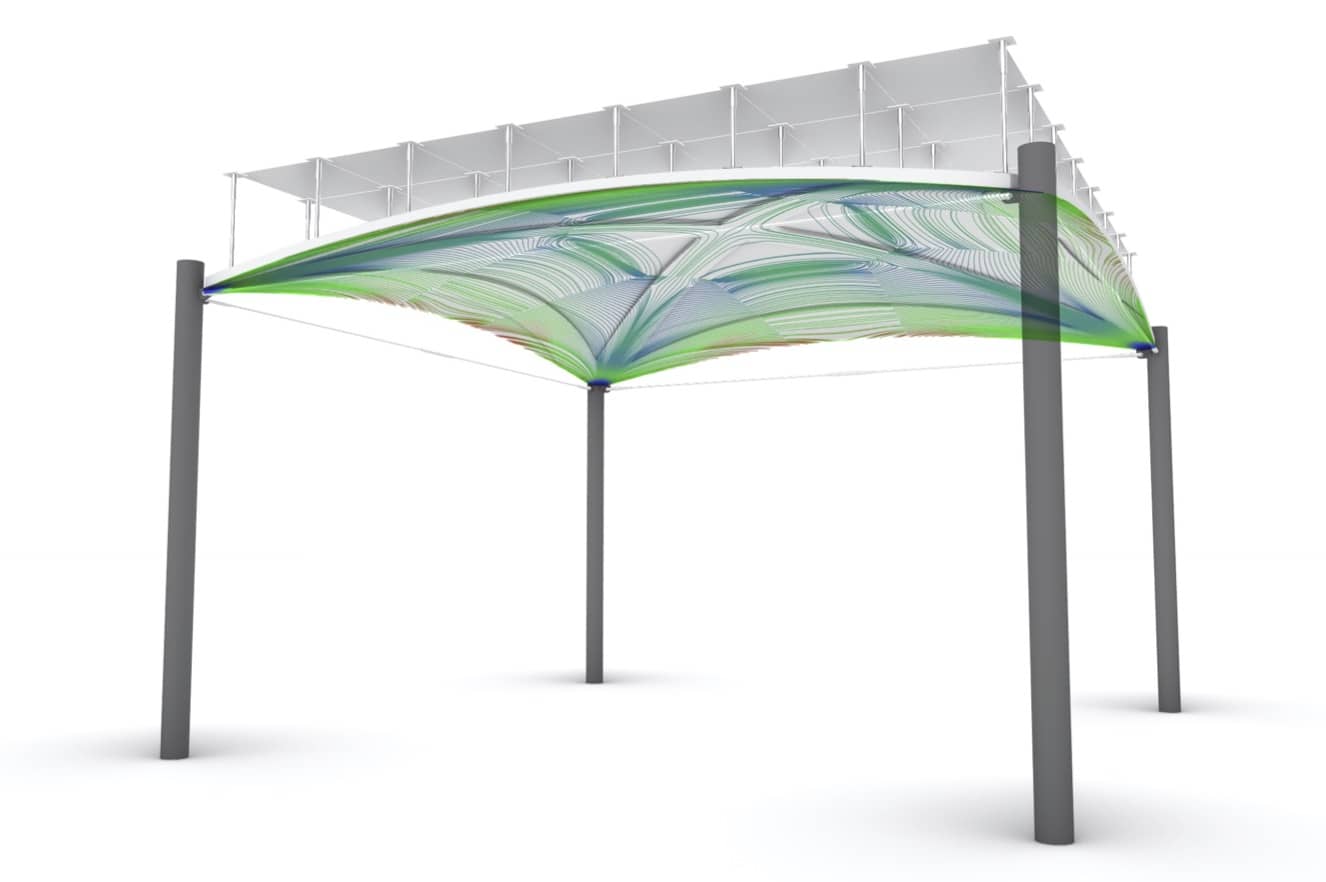

One result of the ACORN research is a thin concrete shell flooring system that uses a quarter of the concrete of an equivalent flat-slab with only 40% of the embodied carbon. The savings in carbon are not quite as high as the savings in concrete volume because the fabrication process requires additives to help the concrete flow through the spray system and also includes short strands of glass fibre reinforcement. However, the team are confident that the embodied carbon could be reduced even further by taking advantage of complementary innovations happening elsewhere to reduce the embodied emissions of concrete. For example, low-carbon cementitious materials are being developed, which could easily fit into an off-site automated manufacturing system. The ACORN team decided against adopting a 3D printing approach, because it is generally very slow and does not scale up to the mass-production context needed to really transform the industry. Instead, they combined a computer-controlled reconfigurable "pin-bed" formwork with a 6-axis robot arm fitted with a concrete and reinforcement-fibre spray system. They developed fabrication-aware software to assist with the design, analysis, optimisation and manufacture of the shells, which were made in transportable segments for later assembly on-site. Each of the nine separate pieces of their 4.5 x 4.5 m demonstrator took about half an hour to make.

The ACORN project is hoping to address connection details, material composition and carry out a more detailed study into Whole Life Value, so that their solution can be de-risked enough to be adopted by a manufacturer. The ideas around minimising material are quickly becoming accepted by industry, as a result of collaborations between academia and industry, as well as through collaborations amongst different industry organisations. Beyond building-elements such as beams and floors, there are concrete-intensive applications in bridges, highways, retaining walls, foundations and marine structures that could also benefit from such an approach.

Society's emphasis on embodied carbon and life cycle assessment will continue. This, together with accompanying regulation, will further accelerate the need to have a more frugal approach to the amount of materials in construction. Research and collaboration can provide useful alternatives for achieving a low-carbon society, but given the construction industry's historic resistance to change, it is likely to need informed clients and motivated governments to begin to demand such innovation, before innovative thin-shell concrete floors will be seen in an office near you any time soon.

References

Lehne, J. & Preston, F. (2018). Making Concrete Change: Innovation in Low-carbon Cement and Concrete. London: The Royal Institute of International Affairs. ISBN 978-1-78413-272-9.

UNEP (2022). Sand and Sustainability: 10 Strategic Recommendations to Avert a Crisis. Geneva: United Nations Environment Programme. ISBN: 978-92-807-3932-9.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.