www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/cop26-illusions.html

COP-26: Stopping Climate Change and Other Illusions

By William E. Rees (Professor Emeritus, University of British Columbia, CA)

Do not expect significant progress from COP-26 on climate change mitigation. There are fundamental barriers that prevent the deep and rapid changes that scientists advocate. Most countries adhere to economic growth policies - which create ecological overshoot. Unless and until we accept that we must live within ecological limits, then climate change will not be adequately tackled. Energy and resource consumption must be addressed through controlled economic contraction.

The world in 2021 was buffeted by an unprecedented barrage of extreme weather events. This is the leading edge of the climate catastrophe that lies ahead should world governments remain fixed on our present global 'development' trajectory.

The good news is that the recent uptick in violent weather has increased pressure on participants in COP-26 finally to implement the kind of determined measures that will dramatically lower GHG emissions and put global heating on hold; the bad news is that whatever is agreed to at COP-26 is unlikely to make any positive difference.

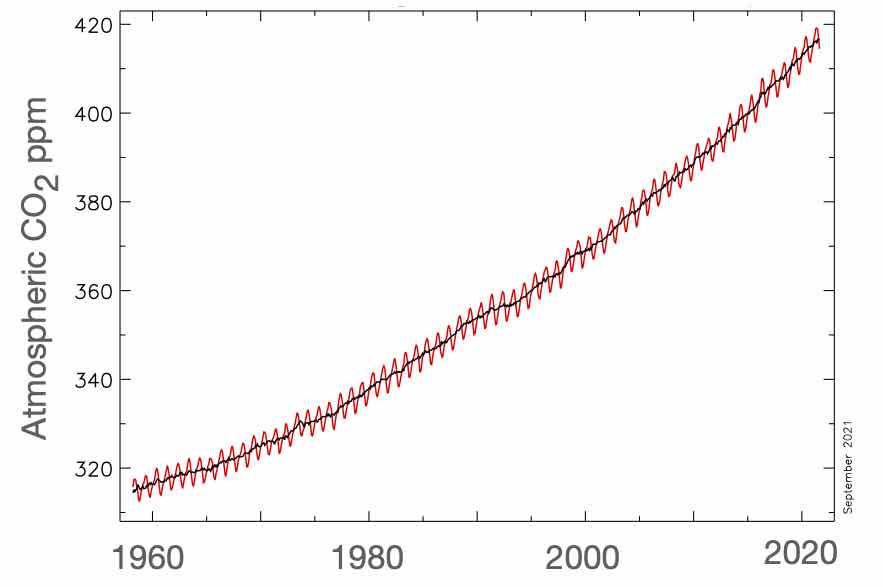

There have been 25 COP meetings on climate change since 1995 and several international agreements to reduce carbon emissions, including the 'legally binding' 1997 Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement of 2015. Nevertheless, atmospheric GHG concentrations have increased unabated during this entire 25 year period - CO2, the principal anthropogenic GHG, has ballooned exponentially from ~360ppm in 1995 to almost 420 ppm in 2020 - and mean global temperature has risen by ~1 oC. History suggests that what should emerge from COP26 cannot emerge from COP26.

There are two fundamental barriers. First, participants in the COP meetings - government negotiators, political and scientific advisors, etc. - constitute a self-referencing cabal whose 'solutions' to climate change draw on the same set of beliefs, values, assumptions and facts that created the problem in the first place. In particular, they are dedicated to unconstrained economic growth propelled by continuous technological development, the beating heart and lungs of capitalism and neoliberal economics. Acceptable approaches to emissions reductions therefore include wind turbines, solar photovoltaic panels, hydrogen technologies, electric vehicles and as yet unproved carbon capture and storage technologies - i.e., any solution that involves the massive capital investment and profit-making potential necessary to sustain growth and the current socio-economic system.

My expectation is that COP26 will maintain the tradition. The latest emissions reduction strategy advanced by many COP participants is Net Zero 2050. NZ2050 implies achieving a balance between carbon emissions and extractions from the atmosphere by mid-century. Indeed, climate models already depend on so-called negative emissions technologies, particularly 'bio-energy with carbon capture and storage' (BECCS), to achieve the Paris target of limiting global heating to under 1.5 oC.

BECCS assumes we can gradually displace fossil fuels by growing biofuel crops to extract large quantities of CO2 from the atmosphere, and then capture and sequester the CO2 emitted when the biomass is burned. The problem is that BECCS is as yet unproved at scale and highly controversial. For one thing, the massive cropland requirement would generate crisis-level conflict with both food production and biodiversity conservation. Some climate scientists see NZ2050 as yet another in a series of "magical yet unworkable" technical (non)solutions to the climate conundrum (Dyke et al., 2021). They argue that the idea of net zero simply continues what has proved to be a "recklessly cavalier 'burn now, pay later' approach" which has seen carbon emissions continue to soar. Spratt and Dunlop (2021) characterize NZ2050 as "not just a goal, but a strategy for COP-26 to lock in many decades of unnecessary fossil fuels use well past 2050... [and creating] unacceptable risks of unstoppable climate warming." These characterizations depict a world in desperation, willing to risk catastrophic climate change in service of a perceived need to maintain growth-oriented business-as-usual-by-alternative-means. Perversely, then, mainstream climate disaster policy seems designed to serve modern techno-industrial society and the capitalist growth economy so the latter appears to be "the solution to (not the cause of) the [problem]" (Spash, 2016, p. 931).

Second, climate change is not even the real problem; ecological overshoot is (Rees, 2020). 'Overshoot' occurs when humanity consumes bio-resources faster than ecosystems can regenerate and waste production exceeds nature's assimilative capacity (see GFN, 2021). In effect, the growing human enterprise is literally consuming and polluting the biophysical basis of its own existence.

Overshoot is a meta-problem: climate change; plunging biodiversity; pollution of land, air and waters; tropical deforestation; soil/land degradation etc., etc., are all co-symptoms of overshoot. Climate change is an excess waste problem - CO2 is the greatest waste by weight of modern techno-industrial (MTI) economies. We cannot solve any major symptom of overshoot in isolation. Indeed, the mainstream approach to emissions reductions will not only fail to subdue climate change but, by promoting material growth, will exacerbate overshoot (Seibert and Rees, 2021). On the other hand, if we eliminate overshoot we simultaneously relieve its various symptoms. The problem is, the only way to eliminate overshoot is, by definition, through some combination of absolute reductions in energy and material consumption and smaller populations, i.e., through controlled economic contraction.

This is why we cannot expect COP-26 to address the human eco-predicament.

References

Dyke, J., Watson, R. & Knorr, W. (2021). Climate scientists: concept of net zero is a dangerous trap. The Conversation (22 April 2021), https://theconversation.com/climate-scientists-concept-of-net-zero-is-a-dangerous-trap-157368

GFN. (2021). Media Backgrounder: Earth Overshoot Day. Global Footprint Network, https://www.overshootday.org/newsroom/media-backgrounder/

Rees, W.E. (2020). Ecological economics for humanity's plague phase. Ecological Economics, 169 (March 2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106519

Seibert, M.K. and Rees, W.E. (2021). Through the eye of a needle: an eco-heterodox perspective on the renewable energy transition. Energies 14(15): 4508, https://doi.org/10.3390/en14154508

Spash, C. (2016). This changes nothing: the Paris Agreement to ignore reality. Globalizations, 13(6), 928-33.

Spratt, D. and Dunlop, I. (2021). "Net zero 2050": a dangerous illusion. Breakthrough Briefing Note (July 2021), https://52a87f3e-7945-4bb1-abbf-9aa66cd4e93e.filesusr.com/ugd/148cb0_714730d82bb84659a56c7da03fdca496.pdf

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Living labs as ‘agents for change’ [editorial]

N Antaki, D Petrescu & V Marin

Post-disaster reconstruction: infill housing prototypes for Kathmandu

J Bolchover & K Mundle

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.