www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/cop26-elephant.html

The Elephant in the Climate Change Room

By Mark Levine (Senior Advisor, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, US)

As the economies and cities in developing countries grow, they will represent the total global increase in GHG emissions through the end of this century. These countries currently have the least capability to limit GHG emissions. In addition to ensuring radical GHG emission reductions in developed countries, COP26 must also now provide a range of significant assistance to developing countries to create local capabilities to reduce emissions. A broad outline is presented of what this entails.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has expressed its view that "acceptable" levels of impact are compatible with a warming of only 1.5 to 2˚C; we are already 60% of the way to 1.5 ˚C temperature increase. Achieving a temperature increase of only 2˚C will be extraordinarily challenging, requiring a global drop in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 50% in 2050 and to zero by 2100. There are regions of the world that have the potential and may also have the political wherewithal to limit their emissions to be compatible with a 2˚C warming. These include Western Europe, China, Japan, the "Four Tigers" of S.E. Asia, and several countries in South America. India and the United States have the potential to follow a 2˚C path but face severe political barriers (very different in each country). Together, these countries represent less than 50% of current GHG emissions.

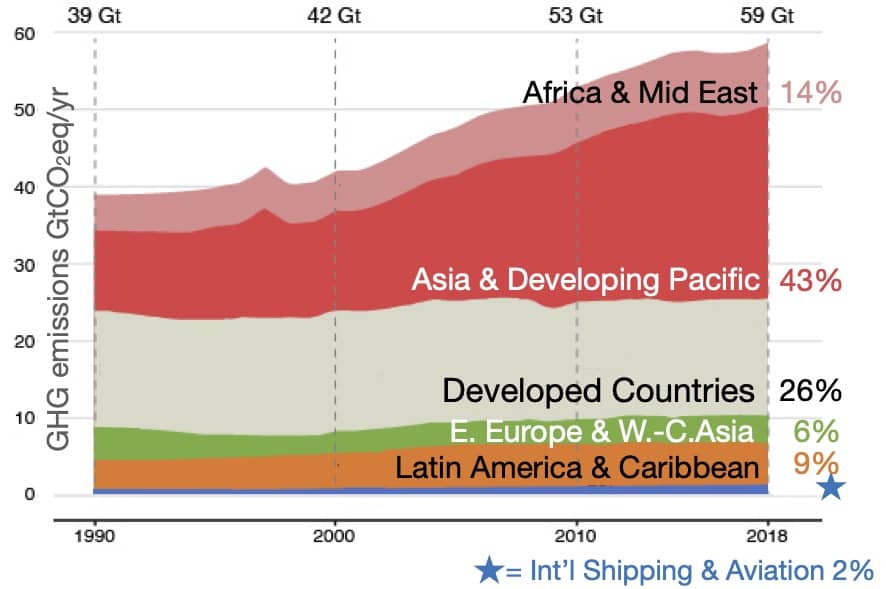

This leaves countries representing more than half the world's population, mostly developing countries, as major outliers. As their economies and cities grow, these countries will represent the total global increase in GHG emissions through the end of this century, as they have during the past three decades (see Figure 1). These countries have the least capability to limit GHG emissions.

It is imperative that there be developed plans and actions to enable developing countries to reduce emissions. As their cities are rapidly expanding, there is an opportunity now to create low-energy and zero-carbon infrastructure and buildings. Such plans need to include the following elements:

- Training for key participants in developing countries in measures and methods to reduce GHG emissions in scale

- Investment in "soft" infrastructure to identify technologies and to design and implement policies for reducing GHGs

- Incentives for investments in GHG mitigation (e.g., solar, wind, or nuclear electricity; energy efficiency for buildings and industry; new equipment to electrify buildings and industry; purchase of EVs)

- Equitable technology transfer to developing countries, making intellectual property available to them, and promoting local production and use

To carry this out, it will be necessary to:

- Create a new type of organization (or even better extend the remit of the Green Climate Fund) to handle the large-scale funding as well as to provide the soft investments that need to accompany the lending.In particular, it will be necessary to make the release of funds contingent on the country taking specific steps that will lead to reduction in GHG emissions.

- Establish one or more training centers in each of the major regions of the world; training would encompass all relevant aspects of design and implementation of GHG mitigation plans including, planning, policy development, finance, engineering, etc. Because most emissions result from activities in cities and buildings, there needs to be emphasis on policies and programs for them.

- Ensure that as large a percentage of the funds as possible are used in the developing countries in order to grow 'green' jobs and provide other benefits to those countries

A recent report of the Green Climate Fund (Hourcade et al., 2021, p. 12) notes the"

"misalignment [of investment] is compounded by the limited capital flows from high-savings to low-savings regions (mostly developing countries). . . .With an estimated $14 trillion of negative-yielding debt in OECD countries and $26 trillion of low carbon climate-resilient investment opportunities in developing countries by 2030. [C]apital seeking higher results should flow from developed countries to developing countries to address this gap. This is not happening. Three-quarters of global climate is deployed in the country in which it is sourced, revealing a strong preference for home-country investments where risks are well understood. This explains why sub-Saharan Africa accounts for only 5% of climate-related financial flows in non-OECD countries."

The redirection of investment flows and associated soft investments are urgently needed. It would be desirable for the leadership of the next (planning) step to be shared by the United States and China, working collaboratively. (China and the U.S. together account for a large portion of global emissions; they worked very effectively together to enable the agreement at the Paris meeting in 2015.) This call to action is both essential and long overdue. Addressing the issues of developing countries needs to be at the forefront of topics to be discussed in Conference of the Parties (COP) to be held starting at the end of October in Glasgow.

Reference

Hourcade, J.C; Glemarec, Y; de Coninck, H; Bayat-Renoux, F.; Ramakrishna, K., Revi, A. (2021). Scaling up climate finance in the context of Covid-19 - Executive Summary. South Korea: Green Climate Fund.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Living labs as ‘agents for change’ [editorial]

N Antaki, D Petrescu & V Marin

Post-disaster reconstruction: infill housing prototypes for Kathmandu

J Bolchover & K Mundle

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.