www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/cop26-agency.html

Avoid Unintended Consequences: Provide Justice and Agency

By Magdalena Barborska-Narozny (Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, PL)

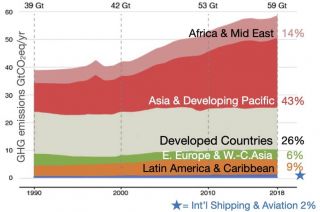

The geopolitics of GHG emission reductions is likely to give competitive advantage to wealthier countries. International climate efforts at COP-26 and elsewhere need to address funding commitments to less advantaged countries. Climate agreements also need to ensure that all counties have suffcient agency to achieve carbon neutrality and are not made vulnerable or disadvantaged.

Climate justice

Mitigating climate change can only be achieved through a redirection of the business-as-usual scenario towards carbon neutrality. This requires top-down context specific interventions in all the greenhouse gas emissions and human activities affecting biodiversity i.e. land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF). Such a massive task cannot be done without putting substantial power and money into the hands of todays' policymakers. Their decisions impact on future generations - the climate they will inherit as well as the financial burden and debt needed to achieve this transition (e.g. EU Covid Recovery Fund). For a timeframe measured in generations, the process of accountability is weak considering the intergenerational and cross-country benefits. These intergenerational responsibilities involve the capacity to track policy impact according to a set of metrics, e.g. changes in energy mix, however care must be taken to minimise the risk of unintended consequences in other areas affected by climate policies, such as deepening the existing inequalities or exacerbating vulnerabilities across and within countries (Baborska-Narozny et al., 2020). The 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals address the need to reach multiple interlocking goals. As Klinsky and Mavriogianni (2020: 414) note: "Climate justice can provide an analysis which is actionable based on understanding whose rights and responsibilities are at play in any given situation and how they are related".

Applying climate justice lens to COP-26 negotiations would be both ethical and pragmatic. It could enable progress of the negotiations while minimising the risk of unintended consequences through a broader consideration of impacts of the strategies adopted at an international or local level.

The COP-26 negotiations aim to develop agreements on how to achieve several defined high level official goals. The first one on the list is accelerating the 'phasing out of coal'.

Poland's decarbonisation

What would a climate justice approach to phasing out coal mean for Poland? This country has been and continues to be highly dependent on coal. Its cumulative emissions (1750-2017) ranks 11th globally. Putting this into perspective, Poland's population of 38 m people is responsible for the equivalent of over 10% of China's GHG emissions and more than half of Africa's or South America's cumulative emissions (Our World in Data, 2021). Globally the country is clearly has responsibilities to reduce its GHG emissions. However, the country's wealth ranks it on the 69th position among 211 countries worldwide and on the 20th position among the 27 EU countries based on GDP per capita index for 2020 (World Population Review, 2021; Eurostat, 2021).

At the macro scale of phasing out coal in Poland, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) was intended to stimulate the discontinuation of coal. However, this mechanism did not achieve the desired outcome. In terms of addressing climate crisis the policy will probably trigger the expected change in the end but at the cost of increasing inequality within the EU block. The EU Member States have developed a proportionate link between wealth (GDP) and the environmental ambition for their Nationally Determined Contributions (UNFCCC, 2020). The ranking of country level commitments for GHG emission reductions between 2005 and 2030 levels beyond the EU ETS closely follows the GDP per capita ranking, with the poorest Bulgaria committing to 0% and the richest Luxemburg committing to 40% cut. Poland committed to 7% cuts.

Fostering responsibility and agency

The link between wealth and environmental ambition may be interpreted as a positive but will have unintended consequences and lead to growing disparities. The wealthy economies will further secure their competitive advantage. Such a scenario follows well known economic patterns but in terms of addressing climate change it should be questioned. The mechanisms for encouraging emissions reductions need to be developed to ensure that countries are not left behind with the problem. The unprecedented EU Covid Recovery Fund seems to be a lost chance in this respect. Even though it has been agreed that 37% of the funds must be allocated on the green transition, such a demand is not specific enough. The key problem areas of each member state in reaching the Carbon Neutral Europe 2050 target are well known and the 37% of the funds should be focused on tackling the top challenges for each country. With Poland's spending plan for this fund, the main problems are again being pushed into the future.

Cutting emissions in the few rich countries will not be enough to address climate crisis. Competitiveness must find a balance with solidarity and the EU Just Transition Fund is a flagship example of such an approach. Interestingly Poland will only be awarded 50% of the country's planned allocation as it declined to commit to implement the objective of achieving climate neutrality by 2050.

Clearly taking responsibility for phasing out coal is too overwhelming for Poland's government to even try at this stage. My expectation is that international climate efforts should go beyond developing funding opportunities. Both careful analysis of past responsibilities but also the impacts of climate policies on the future through the lens of climate justice could avoid the key unintended consequence of the current environmental policies: the lack of perceived agency in striving towards carbon neutrality.

References

Baborska-Narozny, M., Szulgowska-Zgrzywa, M., Mokrzecka, M., Chmielewska, A., Fidorow-Kaprawy, N., Stefanowicz, E., Piechurski, K., & Laska, M. (2020). Climate justice: air quality and transitions from solid fuel heating. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), pp. 120-140. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.23

Eurostat. (2021). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=GDP_per_capita,_consumption_per_capita_and_price_level_indices#Overview

Klinsky, S., & Mavrogianni, A. (2020). Climate justice and the built environment. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), pp. 412-428. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.65

Our World in Data. (2021). https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cumulative-co-emissions?tab=table&country=~OWID_WRL

UNFCCC. (2020). https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/ndcstaging/PublishedDocuments/Poland%20First/EU_NDC_Submission_December%202020.pdf

World Population Review. (2021). https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/countries-by-gdp

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Living labs as ‘agents for change’ [editorial]

N Antaki, D Petrescu & V Marin

Post-disaster reconstruction: infill housing prototypes for Kathmandu

J Bolchover & K Mundle

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.