www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/commitment-regulate-embodied-carbon.html

COP-26: A Commitment to Regulate Embodied Carbon

By Jane Anderson (ConstructionLCA, UK)

Although COP26 is focused on actions by state governments, their commitments are often underpinned by industry. The complexity of embodied carbon in buildings depends on regulation and standards, manufacturer compliance, professional engagement and clear methods / data. We must raise embodied carbon literacy and capabilities across the construction industry to expedite readiness for regulation. Several steps are required and some are already underway.

Embodied carbon describes the greenhouse gases (GHGs) associated with the construction materials and processes used to construct and maintain our built environment, and manage it at the end of life. Estimates vary, but globally, it is around 10% of energy related carbon dioxide emissions (UNEP 2020).

The Netherlands, Germany, France, Sweden, Finland and Denmark have regulations to start to measure and limit embodied carbon in buildings. So far, only the Netherlands has limits in force. The other countries are in the process of implementation which will happen over the next few years in order to ensure adequate training and enforcement are in place.

In the UK, there has been growing interest in assessing embodied carbon in recent years, illustrated for example, by the inclusion of embodied carbon benchmarks in the RIBA 2030 Challenge (RIBA 2021). UK Government has also acknowledged embodied carbon with mention of whole life carbon assessment in the Government's recent Construction Playbook (HM Government 2020). The Welsh Government (2020) has required embodied carbon assessments for all new social housing and the Greater London Authority for larger developments within their jurisdiction (Mayor of London 2021). However, the UK is behind those at the forefront of national initiatives to limit the embodied impacts of construction.

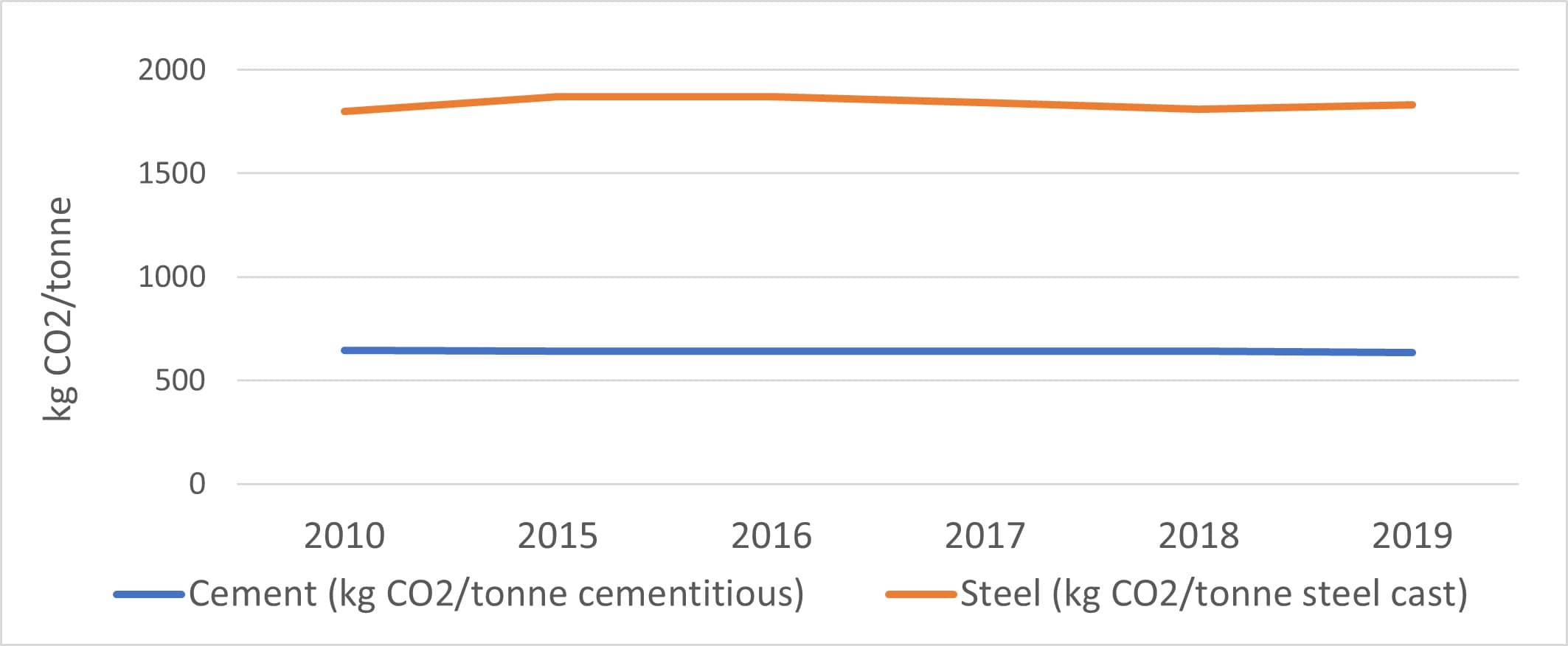

Many construction product manufacturers have committed to achieving net zero by 2050 or before, but there is little recent progress, see Figure 1. Pilots have shown that both steel and cement could be produced without fossil fuels but full-scale production of fossil-free steel is not expected until 2035, and both pilot technologies rely on "green" hydrogen and carbon capture and storage to decarbonise, neither of which are yet viable at the scale required. The wide-scale transformation of existing production plants will be a formidable challenge requiring massive investment.

Regulating the embodied carbon of buildings will focus the attention of architects, engineers, contractors and manufacturers on addressing this impact. Avoiding demolition, considering building form, optimising structure and material efficiency can all make significant savings in embodied carbon, and are likely to reduce costs too. Early in the design process, different material and product options should be reviewed in terms of their embodied carbon impact, when changes are easiest to implement. Contractors must also understand the carbon impacts of changing specifications, and address their materials wastage and energy use.

Regulation at building level should also encourage manufacturers to design more resource efficient products, reduce manufacturing and supply chain impacts and market low impact products using Environmental Product Declarations (EPD). In both Germany and France, the number of EPD rapidly rose with the introduction of their national regulations.

Reviewing the approach in those countries at the forefront of embodied carbon regulation, it is clear that several steps are required. Common steps include:

- a national methodology aligned to EN 15978

- a national database including both generic data and EPD to EN 15804

- a data collection mechanism to enable benchmarking of building level embodied carbon

- a national knowledge hub, providing training and resources

- a mechanism to approve tools that use the national methodology and database.

The UK has already taken steps toward the first three, with the RICS Professional Statement on Whole Life Carbon (RICS 2017), the Inventory of Carbon and Energy (Jones 2019), and the RICS Building Carbon Database (RICS 2019), though all require development to ensure they are ready for use in national regulation.

It is accepted by the construction industry that rapid and significant reductions in GHG emissions are needed. Regulating embodied carbon at the building level would be one way of doing this - by targeting both the way we design and construct and the carbon intensity of products. Although I would wish for much more rapid action to regulate embodied carbon, it is encouraging that the UK's Net Zero Strategy (HM Government 2021) states: "Government aims to support action in the construction sector by improving reporting on embodied carbon in buildings and infrastructure with a view to exploring a maximum level for new builds in the future."

My hope is that COP26 will generate commitments from more countries to start regulating embodied carbon in the built environment. The UK must at use this opportunity to learn from the approaches overseas, in order to adopt best practice when regulation comes. We must also ensure the methodology and databases that are essential for regulation are robust and ready, and that embodied carbon literacy and capabilities across the construction industry involving are raised.

References

GCCA. (2021). GNR Indicator 59cAGWct - World. Gross CO2 emissions - Weighted average excluding CO2 from on-site power generation - Grey and white cementitious products. Global Cement and Concrete Association.

HM Government. (2020). The Construction Playbook: Government Guidance on sourcing and contracting public works projects and programmes.

HM Government. (2021). Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener.

Jones C. (2019). Inventory of Carbon and Energy (ICE Database) V3.0 Beta 7/11/2019. Circular Ecology.

Mayor of London. (2021). The London Plan: The spatial development strategy for Greater London. London. Greater London Authority.

RIBA. (2021). 2030 Climate Challenge (version 2).

RICS. (2017). Whole life carbon assessment for the built environment. London: Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

RICS. (2019). RICS Building Carbon Database. London: Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

UN Environment Programme. (2020). 2020 Global status report for buildings and construction: towards a zero-emissions, efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector.

Welsh Government. (2021). Welsh Development Quality Requirements 2021: Creating Beautiful Homes and Places.

World Steel Association. (2021). Our Indicators.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.