www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/climate-justice-dwellings.html

Climate Justice and English Dwellings

By Jonathon Taylor (Tampere U, FI), Lauren Ferguson* , Anna Mavrogianni* & Clare Heaviside* (*University College London, UK)

The changing climate is expected to have a disproportionate impact on disadvantaged groups worldwide, due to greater exposure - and vulnerability - to various climate hazards. Urgent actions are needed to provide equity through not only providing mitigation measures, but also adapting homes that are most vulnerable to climate effects.

In England, climate change projections show increased average ambient temperatures, and more frequent and severe heatwave events, periods of heavy rainfall and driving rain, and flooding (Betts and Brown, 2021; Lowe et al., 2018). Such events can have serious implications for population health. Around 2,000 deaths are attributed to heat exposure each year in the UK (Hajat et al., 2014), while floods present both acute risks as well as increased levels of psychological morbidity afterwards (Jermacane et al., 2018). Indoor damp and mould growth - for example from driving rain or flooding - is associated with asthma and allergies (WHO, 2009) and poor mental health (Liddell & Guiney, 2015).

Inequality

Housing - meant to provide protection from the temperate English climate - may instead exacerbate exposures to climate hazards in vulnerable groups. Dwellings occupied by low-income communities may be more prone to indoor damp (MHCLG, 2020) and overheat more often (Lomas et al., 2021). While air conditioning in currently rare in English housing, rising temperatures may increase socioeconomic disparities, as active cooling systems are unlikely to be affordable to low-income households (O'Neill et al., 2005). Low-income communities also have higher rates of pre-existing health conditions, making them more susceptible to negative health outcomes (Marmot, 2020), have reduced resilience to damages, fewer financial means or tenure to maintain or adapt their housing, and lower political power to improve the climate resilience of their neighbourhoods. In this regard, parallels can be drawn with the current COVID-19 situation, which has highlighted inequality in England and worldwide, with mortality risks disproportionately high in lower income groups likely due to increased exposure risk, greater underlying health vulnerabilities, and limited financial resilience.

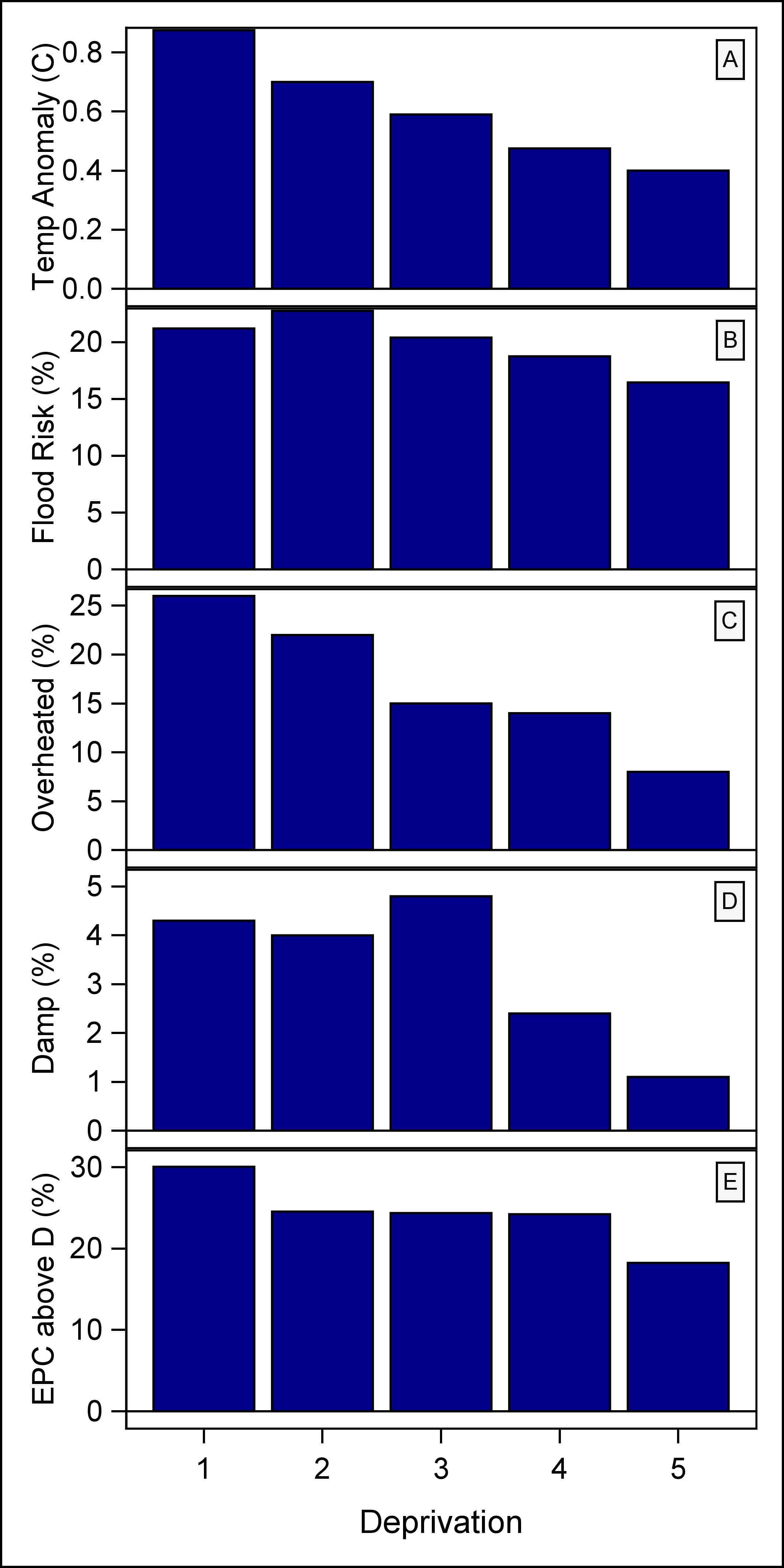

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the role of structural inequalities on health worldwide, and without mitigation and adaptation similar health disparities will also be seen from climate change. There is now increasing evidence of unequal exposures to climate hazards in England (Figure 1), with recent studies finding that low-income communities can experience higher outdoor temperatures during heatwaves (Macintyre et al., 2018) and are at a greater risk of flooding (Hall & Bailey, 2021) relative to other income groups.

This is in contrast with the environmental impact of housing, where the dwellings of higher income groups have a disproportionately negative effect on the environment (MHCLG, 2020). The houses of higher income groups are generally larger and less energy efficient than those of lower income groups, and indeed retrofit rates are highest in low-income areas in England (Hamilton et al., 2014). This inequality between the causes and consequences of inefficiency in the housing stock indicates a degree of climate injustice.

Action

While further changes to the climate are now inevitable, there are opportunities to reduce climate injustice, both through mitigating climate change by reducing GHG emissions, whilst also adapting the built environment to the future climate. Existing inequalities highlight the need for urgent, equitable actions to transform the built environment to improve energy efficiency and climate resilience. In line with the current UK Government policy of "levelling up", government strategies should act to reduce heat and flood risks in the most exposed areas. For housing, the energy efficiency and climate resilience of the existing housing stock should be improved by central government incentives for retrofitting and energy use reduction in households with the greatest emissions. Local governments should be empowered to identify and adapt the homes and households most vulnerable to climate effects, while national building regulations should ensure new homes are adapted to future climates and aligned to climate mitigation targets. While COVID-19 underlined the existence of key structural inequalities and health, there are opportunities to proactively address issues within the built environment that contribute to climate injustice.

References

Betts, R. & Brown, K. (2021). UK Climate Change Risk Independent Assessment (CCRA3). London.

Hajat, S., Vardoulakis, S., Heaviside, C. & Eggen, B. (2014). Climate change effects on human health: projections of temperature-related mortality for the UK during the 2020s, 2050s and 2080s. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68(7): 641-48.

Hall, M. & Bailey, P. (2021). Social Deprivation and the Likelihood of Flooding. Bristol: UK Environment Agency. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/953492/Social-deprivation-_and-flooding-report-v2.pdf (August 27, 2021).

Hamilton I.G., Shipworth, D., Summerfield, A.J., Steadman, P., Oreszczyn, T. & Lowe, R. (2014). Uptake of energy efficiency interventions in English dwellings. Building Research & Information 42(3): 255-75.

Jermacane, D. Waite, T.D, Beck, C.R. et al. (2018). The English national cohort study of flooding and health: the change in the prevalence of psychological morbidity at year two." BMC Public Health 18(330). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5236-9

Liddell, C. & Guiney, C. (2015). Living in a cold and damp home: frameworks for understanding impacts on mental well-being. Public Health 129(3): 191-99.

Lomas, K. J., Watson, S., Allinson, D., Fatech, A., Beaumont, A., Allen, J., Foster, H. & Garrett, H. (2021). Dwelling and household characteristics' influence on reported and measured summertime overheating: a glimpse of a mild climate in the 2050's. Building and Environment, 201: 107986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107986

Lowe, Jason A. et al. (2018). UKCP18 Science Overview Report. www.metoffice.gov.uk

Macintyre, H.L, Heaviside, C., Taylor, J., Picetti, R., Symonds, P., Cai, X.M. & Vardoulakis. (2018). Assessing urban population vulnerability and environmental risks across an urban area during heatwaves - implications for health protection. Science of the Total Environment, 610-611: 678-690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.062

Marmot, M. (2020). Health equity in England: the Marmot Review 10 years on. British Medical Journal, 368:m693. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m693

MHCLG. (2020). English Housing Survey, 2018: Housing Stock Data. London: UK Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government.

O'Neill, M.S., Zanobetti, A. & Schwartz, J. (2005). Disparities by race in heat-related mortality in four us cities: the role of air conditioning prevalence. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 82(2): 191-97.

WHO. (2009). WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Dampness and Mould. Copenhagen.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.