www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/cities-planning-heat.html

Climate Adaptation in Cities: Planning for Heat Vulnerability

By Rohinton Emmanuel (Glasgow Caledonian University, UK)

Urban warming creates a 'double jeopardy' on a majority of humans (urban heat island and global warming). Sufficient information exists to identify where local action is most needed to protect those who are most vulnerable. As a matter of urgency, COP-26, national governments and local authorities need to address heat vulnerability by identifying vulnerable areas and implementing changes in planning practices.

Along with providing more irrefutable proof of the anthropogenic causes of global warming, the recently released 6th Assessment Report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2021) also highlighted the nexus between urbanisation and microclimate and their superimposing effects with global and regional warming. AR6 concluded that 'there is very high confidence that future urbanization will amplify the projected air temperature warming (in cities) irrespective of the background climate' and the effect on nocturnal warming 'could be locally comparable in magnitude to the global GHG-induced warming' (IPCC, 2021: 10-115). Urban growth further exacerbates the possibilities for increases in the frequency and magnitude of extreme events such as heatwaves.

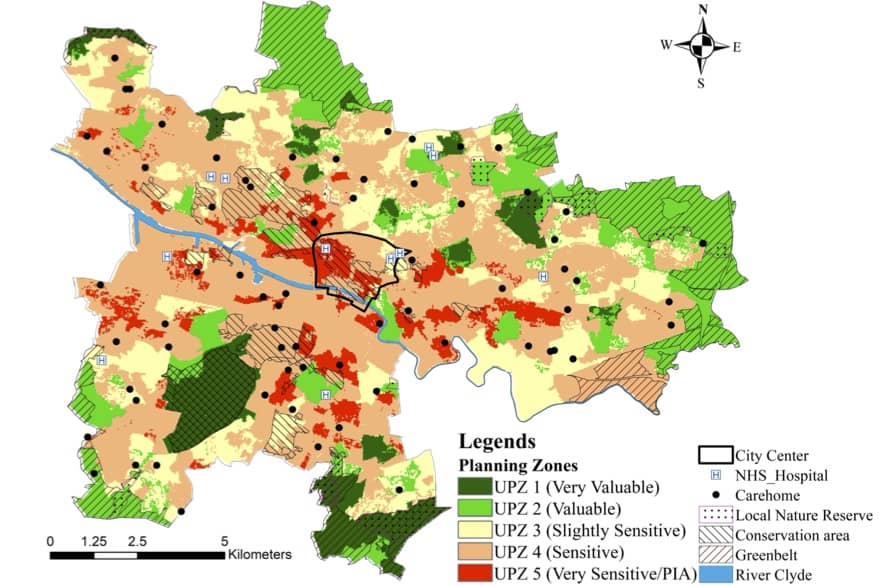

Note: 'UPZ' refers to Urban Planning Zones based on urban climate actions recommended (UPZ1 is highly valuable in terms of ecosystem services provided by existing landscape and therefore no change is needed/allowed; UPZ 5 - areas of high sensitivity to heat vulnerability and where climate action is most needed. Source: Begum (2021).

What can municipalities and urban planners do to address this challenge? A key consideration for adapting to climate change is the impact at the microscale: the microclimate which is influenced by local surroundings and climate context.

Planning action has a vital role to anticipate and adapt to climate change especially the microclimate element as this impacts on individual dwellings, buildings and outside spaces. We must now actively engage with this because urban built form evolves slowly over time. We must ensure that climate change does not exacerbate existing inequalities but act in a manner that equitably distribute the climate change burden.

The good news is that the same variables that lead to local warming (i.e. the way land is used and covered, the configuration (massing) of buildings relative to each other and in relation to streets, the thermal properties of building materials and pollution from human activities, see Emmanuel, 2021) could also be used to map heat vulnerability. Even in the absence of detailed local climate information, such mapping could highlight local areas of relative heat vulnerability at a fine enough scale for planning action to mitigate the negative consequences of local climate change.

Figure 1 shows such an approach to local scale heat vulnerability mapping in Glasgow, the host city of COP-26. No additional data was needed to create such a heat vulnerability map: existing census data on population, climate and land use were used. Super-imposing this on socio-economic conditions in the city ('deprivation' data) gives a first order indication of where vulnerability is at its highest and where adaptation action is most needed.

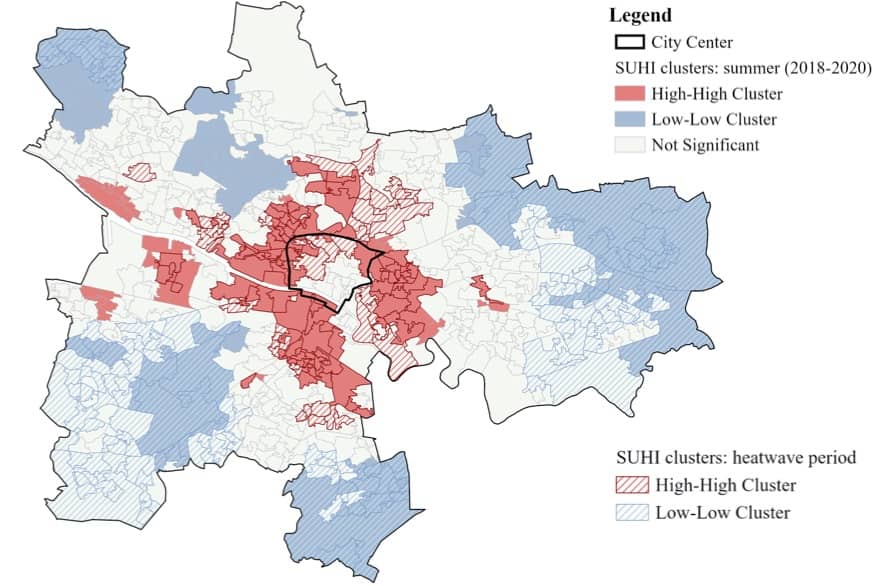

Note: 'High-high' cluster refers to areas where the land surface temperatures are high and spatial auto-correlation is also high; 'Low-Low' refers to areas where both these are low (i.e. 'cool' spots). Source: Ananyeya (2021).

Thus, we have the data and tools to map where the vulnerabilities are at their greatest (as shown in Figure 1) as well as where these are mostly clustered (Figure 2). Utilising this knowledge would help prioritise interventions and also identify where 'more bang for the buck' are likely. The inclusion of socio-economic conditions will foster equitable transition to a climate resilient future.

What is now needed are planning processes finely attuned to local realities to achieve the desired change. These could take the form of wind corridors for natural ventilation, judicious use of waterbodies and green infrastructure to reduce humidity levels, shading arrangements using built massing as well as green infrastructure, provision of shaded and well ventilated open space, as well as building level strategies where relatively modest alterations could lead to significant reduction in heat risk.

While we await intra-national, cross-border structural changes to limit GHG emissions as ultimate mitigation measures arising from COP26, equal emphasis is needed on these relatively low-cost, local adaptation actions that bring about immediate relief to urban dwellers. Given the uncertainties of local climate information, reversibility of local adaptation actions will greatly enhance resilience and nature-based solutions are particularly suited in this regard

References

Ananyeva, O. (2021). Green infrastructure cooling strategies for urban heat island mitigation in cities: case study of Glasgow City Centre, in R. Emmanuel et al. MUrCS Proceedings 2021, LAB University Press, Finland (in press)

Begum, R. (2021). A critical evaluation of different methods of urban climate mapping: a case study of Glasgow, in R. Emmanuel et al. MUrCS Proceedings 2021, LAB University Press, Finland (in press)

Emmanuel, R. (2021). Urban microclimate in temperate climates: a summary for practitioners. Buildings and Cities, 2(1), 402-410. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.109

IPCC (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/#FullReport

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Living labs as ‘agents for change’ [editorial]

N Antaki, D Petrescu & V Marin

Post-disaster reconstruction: infill housing prototypes for Kathmandu

J Bolchover & K Mundle

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.