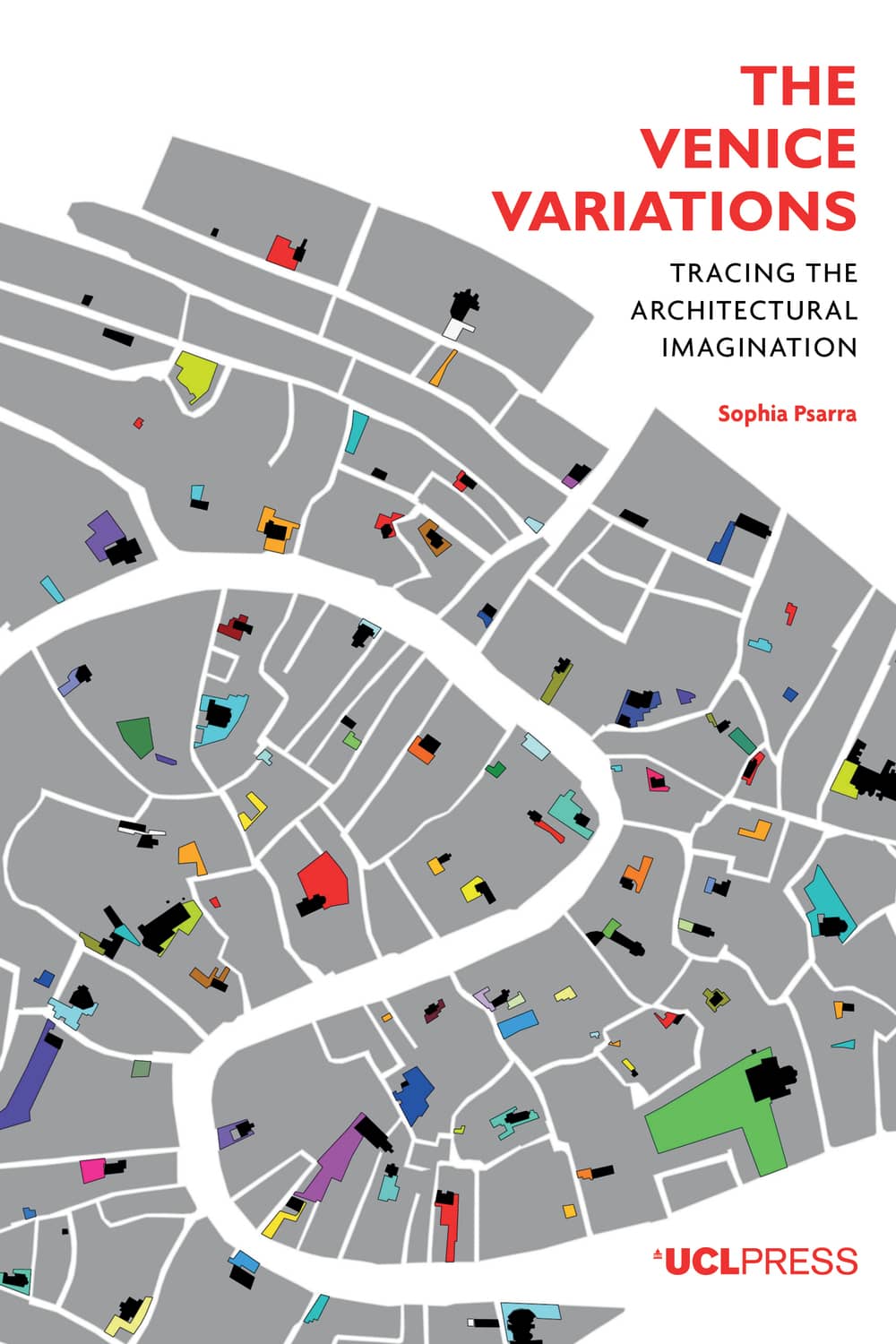

www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/reviews/venice-variations.html

The Venice Variations: Tracing the Architectural Imagination

by Sophia Psarra. UCL Press, 2018, ISBN: 9781787352391

Sherry McKay (UBC School of Architecture and Landscape) reviews this book which considers how the architectural imagination has shaped the spatial history of Venice.

Does the

discipline of architecture possess its own form of knowledge? A possible answer

to this question is proposed through an exploration of architectural discourse

and design as it responded and responds to urban morphology. It is an answer guided

by Bill Hillier's spatial syntax analysis and Henri Lefebvre's identification

of different modes of perceptual, conceptual and lived spaces. The exchange

between these two forms of spatial understanding, one methodological the other

theoretical, is threaded through an historical account of a single city in

Sophia Psarra's The Venice Variations: Tracing

the Architectural Imagination.

Does the

discipline of architecture possess its own form of knowledge? A possible answer

to this question is proposed through an exploration of architectural discourse

and design as it responded and responds to urban morphology. It is an answer guided

by Bill Hillier's spatial syntax analysis and Henri Lefebvre's identification

of different modes of perceptual, conceptual and lived spaces. The exchange

between these two forms of spatial understanding, one methodological the other

theoretical, is threaded through an historical account of a single city in

Sophia Psarra's The Venice Variations: Tracing

the Architectural Imagination.

Space is a much-theorized topic in architectural theory, prominent within this discourse is an ambition to counter its abstraction with an understanding of space as embodied. It has produced the psychogeography of the Situationist international (1957-72), the tripartite conception of space as produced from social practice, representation and representational or symbolic means (Lefebvre, 1974) and spatial syntax analysis (Hillier and Hanson, 1984), among other propositions. Innovative images seeking to represent these alternative conceptions of space have followed. This reorientation is legible in the ambition of The Venice Variations: Tracing the Architectural Imagination to consider history spatially and is augmented by a consideration of the role of architectural imagination in the production of urban space. The book correlates macro and minor urban morphology with economic and social structures, parses the exchange between collective builders and individual architects, recounts the dialogue between imaginative interventions and existing variations of urban form, materially and representationally and charts a path between historical artefacts and contemporary conceptions of imagination and knowledge.

The architectural

imagination is a concept familiar to most design schools. It is exemplified by speculation,

invention and the transformation of precedents. Psarra casts it more

specifically as 'a conscious concern for

crafting space and using geometric

notation to establish coherence against different constraints and requirements'

(p. 225). In this manner, Psarra argues, the architectural imagination can be

expressed as principled knowledge. Psarra also proposes a second form of the imagination at

work in the devising and revising of urban morphology that is collective,

exemplified in the city anonymously crafted by customs, conventions and artisan

practices. The contrasting of architectural with collective imagination allows Psarra

to explore ways of embedding architectural practice in the social and political

practices undergirding urban morphology These two imaginations, especially its

architectural expression, are tracked through an interdisciplinary study of

Venice, drawing primarily on architectural and social histories of Venice and

space syntax analysis of urban infrastructure (canals, streets, well heads) and bodily movement.

Chapter 1 "City-craft: Assembling the city" and Chapter 2 "Statecraft: A remarkably well-ordered

society" develop the theoretical and

methodological underpinnings of the book as well as a narrative about the

social, cultural and political development of

Venice from its founding to the late 16th C. They address

the first half of the subject signaled in the title: The Venice Variations and offer a neatly bifurcated chronology that

serves to correlate urban morphology with social and political structure. "City-craft"

describes an organic city produced collectively by craft persons for a

parish-based society, while "Statecraft" delineates a hierarchical city

produced by the autonomous projects of architects for an oligarchic city

council, pre- and post-Renaissance respectively. Psarra's history of this

corelated shift is rich in description, theoretical exegesis and imagery. The

role of the imagination is insinuated into the narrative as collective

imagination of what she terms the 'unauthored' city and as architectural imagination attributed to the architect of the

'authored city'. Attention to both, unauthored and authored, she concludes, will ultimately reveal the social relevance of

the architectural project.

The following chapters,

4 "Story Craft: Calvino's Invisible

Cities" and 5 "Crafting architectural space: Le Corbusier's Hospital and

the three paradigms" shift focus from the material city of Venice to its

imaginative expression. They explore the

proposition that the complex spatial patterning created by the historical

development of Venice elicits imaginative engagement with the city in the 20th C. "Story craft" examines Calvino's literary work, Invisible Cities,

which encourages readers to imaginatively plot their own course through the

various stories that serve as representations of Venice. In also being a

collective endeavour of author and reader, this chapter mirrors the production

of the "Craft-city." "Crafting architectural space: Le Corbusier's Hospital and

the three paradigms" analyses Le Corbusier's Venice Hospital as a case study of the architectural imagination

responsive to both the city of Venice and conventions and inventions within the

architectural discipline. It mirrors "State craft". These more current case

studies interlace contemporary, architectural and aesthetic concerns with the

historical narrative of Venice's development as social, represented and

representational space.

Venice Variations does not offer an

entirely linear progression, the history explored in the first two chapters

establishes the existing morphology of the city, but little of the specific

social or political context for what is discussed in the subsequent case studies

of Invisible Cities and Le

Corbusier's Venice Hospital. The fifth chapter "The Venice Variations: Tracing

the Architectural Imagination" serves to connect the discussion of the historical

city of Venice with the larger field of the discipline of architecture, remapping

the connection between the city of Venice, Calvino's Invisible Cities and

Le Corbusier's Venice Hospital onto an expanded field of a more theoretical

understanding of the imagination, its inspiration and inventions and knowledge.

The five chapters

of Venice Variations suggest a series

of palimpsests, each successive chapter possessing an evocative impression of

what preceded it. Each chapter offers a network of ideas rather than a singular

line of development; each a web of possible readings allowing multiple

conclusions, which would seem to reflect to some extent Psarra's conception

of both Venice and a design process guided by a disciplined

imagination.

The dialogue between imagination and extant morphology is also evident in the several representations used throughout the book. The diagrams are seductive, colourful and abstract patterns, suggestive of meaning hovering over the quotidian streets, canals and piazzas of the city. While their abstraction is attractive, the meagre labelling often lessens the insight they might offer regarding the spatial practices that Psarra claims produces them. The abstraction of the diagrammatic visual aids is perhaps also calculated as a prompt for imaginative engagement, speculation on possibilities, or invitation to see Venice differently. This objective may explain the vagueness of the network diagrams or the inclusion of GIS models that do not seem to add much to the discussion otherwise.

Venice Variations: Tracing the Architectural Imagination proffers an imaginative and ambitious account of urban development

and the architect's means of engagement with it. The text is expansive, offering a virtuoso display of different

modes of knowing. But equally, the breadth of material gathered into a single

locus and the complexity of the narratives woven into each chapter and across

the book as a whole may be disorienting to some readers. The quantity of

material gathered into some 260 pages of text has meant that some concepts are given

truncated treatment and some material appears tangential. Some readers

unfamiliar with contemporary architectural discourse may find the significance

of Bill Hillier's 'generic' city (p. 59) dimmed and the criticism of digital

technologies' entanglement with neoliberalism (p. 16) blunted by a lack of

explication. Some exegesis seems to make

only an attenuated contribution to the main points of the argument. As

interesting as the discussion of the map of Manhattan is, it does not clearly

contribute to the overall thrust of the book (p. 72-75), while the brief

discussion of the 15th C portrait of Luca Pacioli over complicates

the discussion of representation (p. 135-6). The numerous spatial analyses of

modern architectural projects by different architects and for different

locations included in a chapter dedicated to Le Corbusier's Venice

Hospital seem to unnecessarily over-burden the argument.

The book is both a history and a proposed methodology, a concatenation of erudition and imagination, it is both about Venice and refers to elsewhere. It offers a rather circuitous route to making the point that the architectural imagination can access and direct toward contemporary needs and contribute to social capital. Psarra asserts that The Venice Variations: Tracing the Architectural Imagination does not offer solutions for the contemporary problems of the city or for its ongoing environmental degradation. But why doesn't this wide-ranging and theoretically rich analysis of the architectural imagination not provide insights, if not answers? What is the relevance of an architectural imagination that does not engage with such social and political concerns. The book certainly suggests why it would be important for it to do so.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.