www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/reviews/dwelling-future-architecture.html

Dwelling on the Future: Architecture of the Seaside, Middle England and the Metropolis

By Pierre d'Avoine. UCL Press, 2020, ISBN: 978-1-78735-054-0

Dean Hawkes considers an essential question: 'Can design be research?' Against a background of numerous publications that emanate from schools of architecture, the place of design as a mode of enquiry remains controverial.

The series, Design Research in Architecture, from UCL Press, seeks to answer the question by publishing books that present exemplars of practice as research. Pierre d'Avoine occupies a distinctive place in British architecture as a practitioner and teacher and his latest book, Dwelling on the Future, draws on both roles to offer insights into the nature of housing in contemporary Britain.

At

the heart of the book are twelve projects. These range, in scale, from the single dwelling to large scale

developments and, in location, from Seaside,

Middle England and the Metropolis. d'Avoine's method is to combine conventional

architectural representation, in the form of elegant line drawings, with texts

that derive from interviews that he has conducted with important protagonists (collaborators, consultants, clients) - private and commercial, developers,

planners - whose words provide rich, often idiosyncratic, context to each

project and serve to illustrate something of the social, institutional and

cultural background to the production of housing in modern Britain. These alone are a valuable research contribution

and acquire further significance when read in conjunction with the design

projects.

The

idea of Seaside is explored in four

projects. Just one, Pleasure Holm on

Birnbeck Island at Weston-super-Mare, is literally at, even in, the sea. The work-live units at the Aberystwyth Arts

Centre are located on the hill to the north of the coastal town and the two

remaining projects, Crocombe Court in Somerset and Bengough's House on the

outskirts of Bristol, are both some distance inland. However,

there is a sense that the sea is near, as suggested by James Turrell's observation (quoted in Lilley and Bugler, 2006) on

the quality of the English skies, that, 'You realise that England is at sea',

made in 2006, on completion of his 'Skyspace' at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Middle England is here adopted to

define locations that lie in the centre ground between the coast and the

metropolis. The five projects cover

territories from the magical landscape of Glastonbury to the World Heritage

Site of the Derwent Valley at Belper in Derbyshire, Swaythling in the suburban

belt of Hampshire between the cities of Portsmouth and Southampton, rural

suburbia at Crouches Field in Kent, the 'Garden of England', and, finally, Letchworth Garden City, the birthplace of

modern English suburbia. To explore the Metropolis there are just three projects,

one in Suburbia the others the Inner City. Together these do not constitute a

comprehensive urban vision, a Ville Radieuse, but reveal something of

the intricacy of the ground in contemporary London. To convey something of d'Avoine's method, a selection of the projects is summarised below.

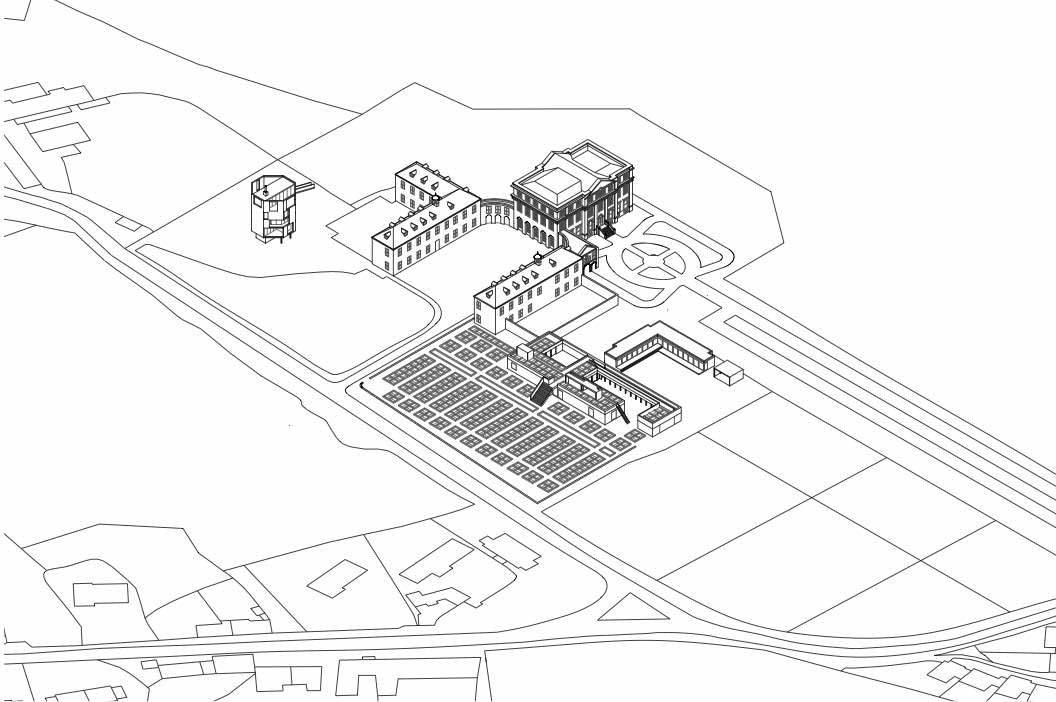

Crowcombe Court , a Seaside project, is a Grade 1 listed, eighteenth century baroque house, some 10 kilometres from the Bristol Channel at the foot of the Quantock Hills. It is now used as a wedding venue and the brief was for a new house in the grounds for the owners, plus two other houses. The questions of building in relation to historic buildings in the landscape are widely explored in d'Avoine's interview with historic landscape consultant, Kim Auston, with whom he worked on the project. From this emerges acceptance of the validity of the new and the design is subtle in siting, form and detail in relation to the existing house. The owner's introverted single-storey house sits, semi-buried on the edge of the former walled garden. An L-shaped house is placed to the west of this and a striking 'drum' house, octagonal in plan, is more distant. Illustrated in beautiful isometric and planometric drawings, the ensemble is a convincing evolution of the site's history.

In

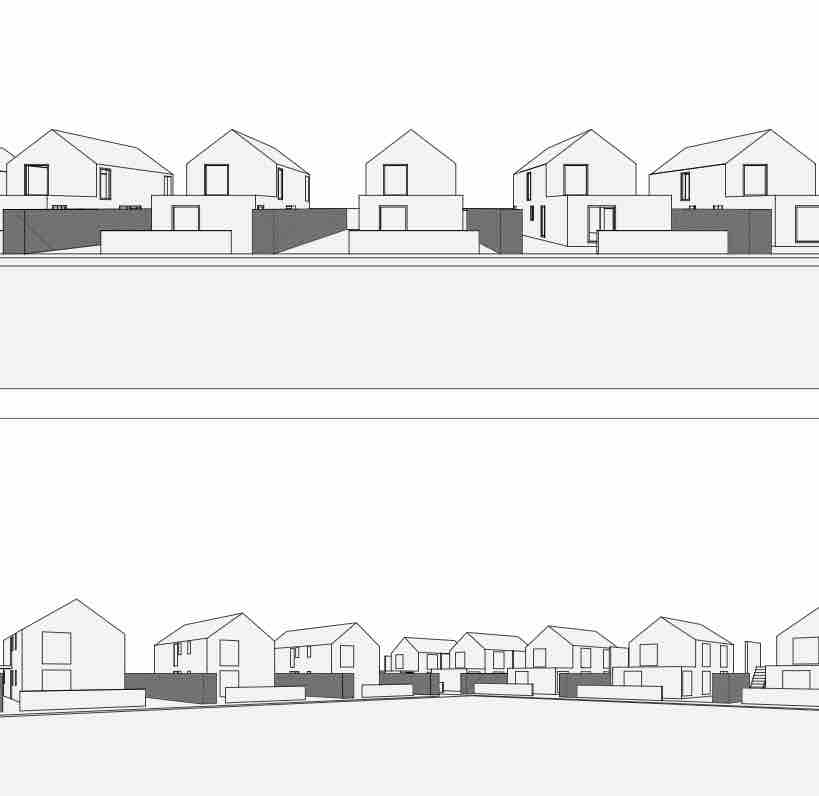

Middle England, Letchworth Garden

City is the site of Ebenezer Howard's first garden city, planned by Barry

Parker and Raymond Unwin. The method

here is typological, with detached houses, derived from the density and

principles of the garden city, grouped in court arrangements, Patchworks, and illustrated disposed in the landscape of

Aspley Guise, a site ripe for development, not far to the north of Letchworth. I find it interesting that, working a century

later, d'Avoine's proposal closely parallels Unwin's (1912) analysis in his pamphlet, Nothing Gained by Overcrowding,

in which he drew a comparison between two distinct 'types', perimeter

arrangements of short terraces of houses and the parallel terraces of the bye-law street.

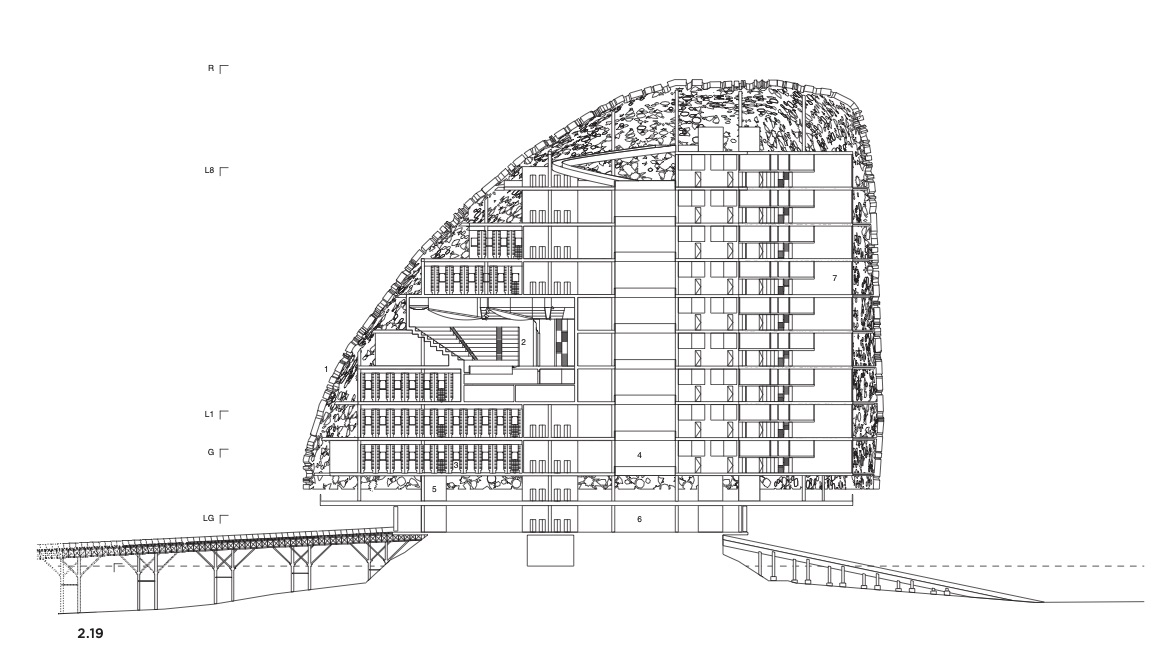

Two projects in London bring us to the Metropolis. In the first on a former industrial site in west London, the proposal is for a slender Pencil Tower of apartments, with alternative heights of 10, 20 or 30 storeys. In an interview with developer Crispin Kelly, reference is made to a suggestion by Deyan Sudjic (2016) that to qualify as a 'world city' London should look something like Shanghai. The 'tower question' is further developed in the final project, Pembury Octagon, in which an elegant eight-storey tower of apartments is placed, tempietto-like, in the three-sided court of a block of Peabody flats in Hackney. An interview with Liam Dewar (a director at Eurban) explores the potential of timber structures in such buildings. In response to the provocation of Sudjic's statement, it is accepted that towers have a place in the conception of the modern city. But the question in my mind is whether all 'world cities' should look the same, regardless of culture, history or climate.

In the Postscript d'Avoine draws a broad parallel between his 'journey' through these projects and J.B. Priestley's (1934) literary English Journey. The precedent for Priestley's book and for others of the genre, such as George Orwell's (1937) The Road to Wigan Pier, was William Cobbett's (1822-1826) Rural Rides, on horseback in the southern counties in the second decade of the nineteenth century. This also inspired the principal, specifically architectural precedent for an English journey, Alison Smithson's (1983) AS in DS: An Eye on the Road, in which she reported on the prospect of England as seen through the windscreen of the Smithson's much loved Citroën 'DS' model car:

'This is a diary of car-movement recording the evolving sensibility of a passenger in a car to the post-industrial landscape.'

In Dwelling on the Future, the 'journey' provides the frame within which d'Avoine organises and presents his sequence of explorations into housing questions in modern Britain. The device is effective in bringing structure to the diversity of site, scale and programme within the ten projects.

Architect and educator Leslie Martin (1967) concluded a talk at the Royal Institute of British Architects in London, in which he set out the broad agenda for the research that he was initiating at Cambridge University's school of architecture, by saying:

'The ultimate problem for the profession is that of setting out the possibilities and choices in building and environment.'

In this valuable book Pierre d'Avoine achieves precisely that. His projects, individually and in sum, are 'possibilities and choices' for housing in the 21st century. Architectural research has travelled a long way since Martin and the other pioneers laid the ground, not least in the recognition of 'design as research'.

References

Cobbett, William. (1822-1826). Rural Rides, Political Register (London). Reprinted 1967, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Lilley, C. and Bugler, C. (2006). James Turrell Deer Shelter. Bretton: Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Martin, Leslie. (1967, May). Architect's Approach to Architecture, Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects.

Orwell, George. (1937). The Road to Wigan Pier. London: Gollancz.

Priestley, J.B, (1934). English Journey. London: Gollancz.

Smithson, Alison (1983). AS in DS: An Eye on the Road, Delft: Delft University Press. Reprinted 2001, Baden, Switzerland: Lars Müller Publishers.

Sudjic, Deyan, (2016). Whatever Happens to Britain, London Will Remain a City State. Evening Standard Online.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Living labs as ‘agents for change’ [editorial]

N Antaki, D Petrescu & V Marin

Post-disaster reconstruction: infill housing prototypes for Kathmandu

J Bolchover & K Mundle

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.