www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/personal-carbon-allowances.html

Can Personal Carbon Allowances Help Cities Reach Their Climate Targets?

Could a focus on city dwellers to reduce individual emissions - personal carbon allowances - have value in meeting city Net Zero targets?

Many cities throughout the world have set carbon and / or energy targets including renewable energy production and emissions reduction goals. Despite the commitment to take action, cities do not directly control the majority of the uses of energy or consumption-related sources of carbon emissions within their boundaries. Could a focus on household energy use, personal travel and consumption of material goods help to achieve this transition at city level? Tina Fawcett (University of Oxford), Kerry Constabile (University of Oxford) and Yael Parag (Reichman University) consider whether and how cities could harness personal carbon allowances in a practical manner.

Cities and climate change action

To reach cities' Net Zero goals, urban energy demand and material consumption must be reduced, and remaining demand met using renewable and low carbon sources of energy. With Net Zero specifically, as opposed to zero or carbon-free targets, emission offsets and Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) options can also make a contribution.

City authorities are directly responsible for only a small percentage of their local area's emissions - estimated at 2-5% in the UK (Marix Evans, 2020). However, city leaders and local authorities hold a number of roles in which they can deliver or influence city-wide carbon savings. This may include:

- building owners and managers (especially of social housing) can install new energy efficiency measures, local renewable energy systems and reduce fuel poverty

- incentivising the use of public transport

- decarbonising public transport

- land use planning authorities can change zoning laws to encourage densification, reducing building energy demand and the need to travel

- city-based business leaders can use convening power to reduce energy demand

- developing measures through local economic plans and policy.

While these are critical levers and roles, they remain insufficient to deliver local authorities' Net Zero ambitions.

Cities have limited tools for tackling consumption emissions that are the result of individual actions, choices and lifestyles. For example, cities can provide lower carbon transport options (by making walking and cycling easier and local public transport more attractive), but they cannot prevent people buying large fossil-fuelled cars and driving them long distances, or dissuade people from frequent flying - both significant sources of transport emissions. Addressing the 'over consumption' of high emitters is particularly challenging.

To meet Net Zero, city leaders will have to think beyond residents' energy use, to include their material consumption. A city's Scope 3 emissions - the goods and services consumed within cities yet produced outside of their boundaries - are often undercounted and are very difficult for cities to address. Recent academic literature and publications by cities networks such as C40 suggest that the emissions of some megacities are up to 60% higher when accounting for consumption-based emissions (C40 Cities 2018). To tackle the full climate impact of a city, there is a need for improved consumption-based scope 3 assessments and comprehensive reduction strategies, which will require a collaboration between city residents, organizations and governments. While some consumption-based emissions can be managed through city procurement strategies, this will only cover a small proportion of these emissions.

Thus, to help meet their Net Zero roles, city authorities need policy tools which can engage individuals, and encourage or mandate lower carbon choices related to household energy use, transport and material consumption.

Personal carbon allowances

Personal carbon allowances (PCA) is a policy idea focusing on individuals, which was developed for use at national level. The policy proposes a cap on carbon emissions, which reduces over time. Each individual gets an equal carbon allowance, and these are tradable, to enable high emitters to buy spare allowances from lower emitters (also known as personal carbon trading, or PCT). There are different proposals for the scope and detailed design of this idea (Fawcett & Parag 2010), but all have a common aim of reducing carbon emissions in a fair way by informing and engaging citizens in the process.

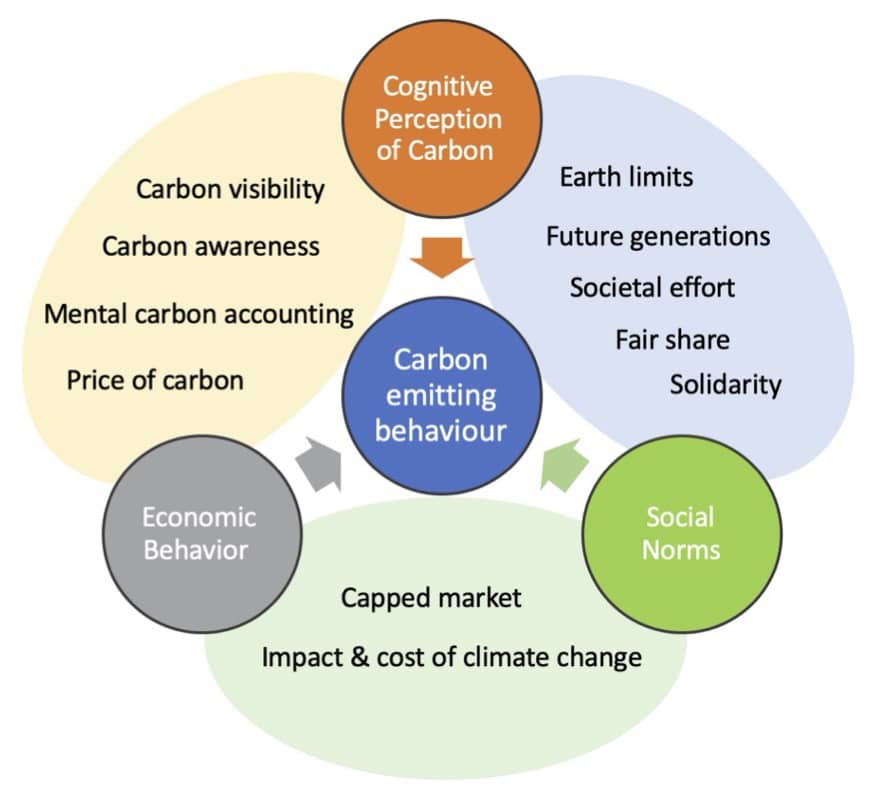

PCT is theorised (Parag & Strickland 2010) to encourage personal emission reduction through three interlinked mechanisms (Figure 1):

- economic: the carbon price which puts a price tag on every unit of personal emissions

- cognitive: the visibility of carbon, which leads to an increased awareness of personal emissions, and encourages carbon accounting

- normative: the creation of new social norms of low carbon lifestyles with which everyone has to comply .

This policy has not been adopted anywhere the world, although elements of it have been tested in various locations on a voluntary basis. At its simplest, this policy could cover personal transport, household energy use or a combination of the two. For cities, these are two areas where energy use and carbon emissions must be reduced, and over which city authorities have limited existing levers of control. It could be further extended to cover the carbon embodied in building materials, goods and services, but this presents a greater data challenge.

Cities, personal carbon allowances and voluntary trials

While PCA/T was originally conceived as a mandatory national policy, it seems very unlikely that a mandatory carbon allowance policy could work at city level - apart from anything else, there would be nothing to stop local residents buying transport fuels from outside of their city area, making local limits inoperable. However, a voluntary version of PCA / Net Zero scheme, whereby citizens are given information, accounting tools, rewards for lower carbon behaviour, and offsetting options within their own city limits seems more plausible.

What might such a city-level scheme look like? Like PCA, a voluntary Net Zero carbon scheme will be based on data that promotes carbon literacy and carbon accounting and that also suggests ways to reduce carbon impact. A mobile app is likely to be the engagement platform, which provides accessible information about the personal carbon emissions associated with various energy-related activities, such as energy use in the household or the use of private/personal transport. The app could also provide relevant, nearby and easy-to-access low-carbon alternatives to these activities, as well as a list of local offsetting options (e.g. within the building or neighbourhood). Groups of users within the same building, community or neighbourhood may work together to reduce and/or offset their emissions. Being familiar with their residents, city leaders may support or fund coordinators to help such activities to form and materialize, for example, by harnessing community key figures, by convening or approaching local businesses and/or by funding events.

There are carbon and beyond-carbon benefits of information and incentive schemes delivered at city rather than national level. If designed in advance, these benefits include strengthening the local economy by encouraging the use/deployment of local low carbon products, services and professionals, as well as potentially developing local offsetting businesses. The collective and personal reduction goals could lead to collective action, at the building, neighbourhood or district levels, which in turn may strengthen the societal resilience of local communities. The incentive to provide local low carbon alternatives could offer opportunities to create local 'living laboratories', that develop tailored and fit-for-purpose low carbon innovation from the bottom-up.

There have already been city trials of related ideas. For example, in Rotterdam 2000-03 the NU-Spaar savings programme was a consumer incentive system to promote sustainable purchasing behaviour. It was based on a loyalty smartcard which rewarded behaviours with points which could be traded in for environmentally friendly goods and services.At its peak, the project included 10,000 cardholders and 100 participating shops (Joachain & Klopfert 2011).More recently, the Finnish city of Lahti has experimented with a personal carbon trading system for transport choices. It developed a public carbon-trading scheme and digital application for its residents, which was in use 2020-21. Based on a co‐creation process, a citizen‐specific allocation method was selected for emission allowances. Each person got the same basic allowance, with an additional allowance for factors such living at a greater distance from services or mobility problems. The app, for smartphones and mobile devices, allowed people to earn credits by using environmentally friendly forms of transport. This pilot scheme showed that it is possible to implement a voluntary PCT system using ICT technology. Of the final survey respondents, 36% felt that their mobility produced less emissions than previously, and the key reasons were the information received about personal mobility emissions, desire to challenge themselves and rewards received through PCT (CitiCAP 2021).

Concluding thoughts

Cities are often in a better position than national government to effectively engage with and influence their residents. This makes cities good locations to trial elements of PCA to help meet Net Zero goals. Indeed, voluntary schemes, using rewards rather than penalties, have already been shown to be implementable and effective on a relatively small scale. Although focused on individuals, this policy could engender collective action at a variety of scales, and deliver co-benefits beyond carbon emissions.

There are still important questions to ask. How would city leaders know if this policy is working, and what would it cost? If introduced as a voluntary scheme with no penalties, what degree of change would we expect to see? How would it fit with other policies in the city, e.g. investment in active transport infrastructure? What percentage of the population is likely to get involved, and who might be excluded?

Assuming these questions can beanswered satisfactorily, first movers, progressive cities with a tradition of climate action could run more pilot schemes. If successful, existing low carbon / environmental city networks provide ways of learning from best practice. Expansion of city-level schemes could also be a forerunner of mandatory national schemes. In conclusion, PCA is promising as a route to helping cities deliver their Net Zero targets by engaging their populations in choosing lower carbon energy demand and/or material consumption options.

References

Akenji, L.; Bengtsson, M.; Toivio, V.; Lettenmeier, M.; Fawcett, T.; Parag, Y.; Saheb, Y.; Coote, A.; Spangenberg, J.H.; Capstick, S.; Gore, T.; Coscieme, L.; Wackernagel, M.; Kenner, D.; Kolehmainen, J. (2021). 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: Towards A Fair Consumption Space for All. Berlin: Hot or Cool Institute. https://hotorcool.org/1-5-degree-lifestyles-report/

C40 Cities. (2018). Consumption based emissions of C40 cities. C40 Cities Knowledge Hub. https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/Consumption-based-GHG-emissions-of-C40-cities?language=en_US

CitiCAP. (2021). CitiCAP - Citizens' cap and trade co-created. City of Lahti, Finland. https://www.lahti.fi/en/files/citicap-final-report/ .

Fawcett, T. & Parag, Y. (2010). An introduction to personal carbon trading. Climate Policy 10: 329-338.

Joachain, H. & Klopfert, F. (2011). Emerging trend of complementary currencies systems as policy instrument for environmental purposes: changes ahead? [working paper]. Brussels: Universite Libre de Bruxelles. https://bit.ly/3PCp65E.

Marix Evans, L. (2020). Local authorities and the Sixth Carbon Budget: an independent report for the Committee on Climate Change. London: Committee on Climate Change. https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/local-authorities-and-the-sixth-carbon-budget/

Parag, Y. & Strickland, D. (2010). Personal carbon trading: a radical policy option for reducing emissions from the domestic sector. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 53(1): 29-37.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.