www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/hackitt-the-golden-thread-challenges-to-implementation.html

Hackitt and the Golden Thread: Challenges to Implementation

Will the Hackitt Review recommendations be easily implemented?

Graham Spinardi (University of Edinburgh) explores the implications of the Hackitt Review into fire safety regulation following the Grenfell Tower disaster. In particular, he considers the challenges to implementing a digital 'golden thread' of building information throughout a building's life cycle.

Introduction

After the June 2017 Grenfell Tower fire, the Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety was established to provide a thorough examination of the failings of the English regulatory system for fire safety. This review was led by Dame Judith Hackitt. The final report published in May 2018 called for 'a radical rethink of the whole system and how it works' (Hackitt 2018, 5). Her damning verdict (Hackitt 2018, 11) on the current system concluded that:

- 'regulations and guidance are not always read by those who need to, and when they do the guidance is misunderstood and misinterpreted

- 'that there is ambiguity over where responsibility lies'; and that regulatory oversight and enforcement is inadequate with enforcement 'often not pursued'

- 'competence across the system is patchy'.

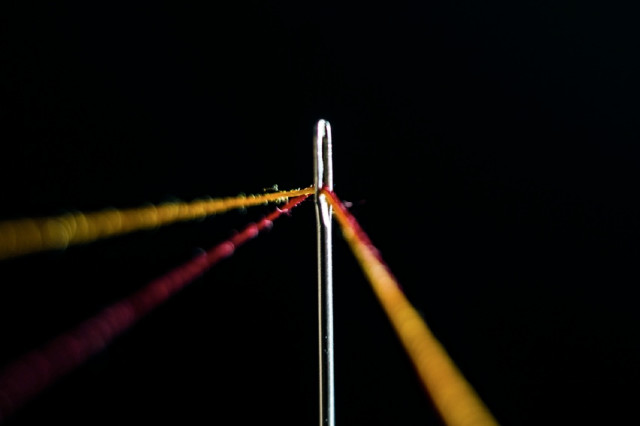

While Hackitt's main argument was that fire safety regulation should emphasise an 'outcomes-based' approach rather than one based on compliance with rules, the focus here is on Hackitt's recommendation to establish a digital 'golden thread' to 'ensure that accurate building information is securely created, updated and accessible, at points throughout the building life cycle' (Hackitt 2018, 102). As Hackitt highlights, this is desirable to ensure that building safety management can be done with full knowledge of the original fire safety design, and of any subsequent changes.

Pre-Grenfell fire safety regulation

Historically, fire safety regulation in the UK has been divided into two separate phases: pre-construction regulation covers approval of building design whilst post-construction regulation covers the building's occupation and use. The specific regulatory mechanisms at the time of the Grenfell Tower fire were the Building Regulations 2010 for design approval and the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order (RRFSO) 2005 for post-construction regulation.

In essence, the RRFSO requires that the 'responsible person' should carry out a 'suitable and sufficient' fire risk assessment for a premises, and put into effect any mitigation efforts that are indicated.Where a workplace is concerned, the responsible person is the employer 'if the workplace is to any extent under his control'; otherwise, it is 'the person who has control of the premises'.Post-construction regulation since 2005 has thus been largely a matter of self-regulation, with local Fire Authorities providing some oversight for those buildings (e.g. night clubs or care homes) considered to involve greatest risk (Spinardi et al 2019).

Hackitt (2018) identified a number of flaws in the operation of this approach to post-construction regulation, including the limited oversight of the process (in many cases no one checks that a fire risk assessment has been carried out or has been acted on), and the lack of any specific requirements for competence for those carrying out fire risk assessments (see also Spinardi et al 2019). One specific problem is that in many cases the responsible person, or their designated fire risk assessor, does not have access to the original fire safety design information.

The existing mechanism for the handover of

design information to the building user relies on the provisions of Regulation

38 of the Building Regulations, that requires that the 'person carrying out the work shall give fire

safety information to the responsible person not later than the date of

completion of the work, or the date of occupation of the building or extension,

whichever is the earlier'.

This approach has two crucial failings (Spinardi et al 2019). First, there is no means of enforcement, nor any oversight other than to require the project developer to sign a declaration that they have provided the fire safety information. No check is made on its contents or that it has actually reached the responsible person. Indeed, the requirement to transfer the information on the completion of the work may be impractical because the responsible person may not yet be in situ. Moreover, even when the design information is made available to the first occupier of a building, there is then no mechanism to ensure that subsequent occupiers gain access to the information. Second, even when the responsible person is able to locate the fire safety design information, it may not be in a form that is useful to them. There is no standardised format for providing this information. Nor is there any requirement for the responsible person or a delegated fire risk assessor to have any particular level of competence to understand it.

Hackitt report recommendations

The final Hackitt report focussed on Higher

Risk Residential Buildings (HRRBs) and recommended that: 'Government should

make the creation, maintenance and handover of relevant information an integral

part of the legal responsibilities on Clients, Principal Designers and

Principal Contractors undertaking building work on HRRBs' (Hackitt 2018, 36).

Hackitt proposes three gateways for regulatory approval with the first

consisting of planning approval and the second of design approval. The move to

building occupation would then require approval at Gateway 3, which would

include satisfying a newly established regulatory authority (what Hackitt calls

the Joint Competent Authority or JCA) 'that all key documents have been handed

over' (Hackitt 2018, 38).

The purpose of this Gateway 3 requirement is to 'ensure that the future building owner will receive the key golden thread information products, linking the design and construction and the occupation and maintenance phases together… [in order to] complete a pre-occupation Fire Risk Assessment based on the Fire and Emergency File that is ready for occupation as well as a resident engagement strategy' (Hackitt 2018, 40). Information 'must be transferred when building ownership changes to ensure that the golden thread of information persists throughout the building life cycle' (Hackitt 2018, 105). Not only would the responsible person be expected to carry out regular fire risk assessments, but also there would be a requirement to present a 'safety case' to the regulator at least every five years, or whenever there is major renovation (Hackitt 2018, 56).

Better control of fire safety during a

building's lifetime would be ensured by requiring 'robust record-keeping by the

dutyholder of all changes made to the detailed plans previously signed off by

the JCA', with significant changes requiring permission from the JCA (Hackitt

2018, 12). According to Hackitt (2018, 35): 'As soon as detailed work commences

the client needs to ensure that a digital record of the building work is

established and a Fire and Emergency File is initiated. Both of these

will need to be maintained throughout design and construction and be part of

the regulatory oversight process.'

Amongst the information that Hackitt (2018,

104) proposes to be recorded are: 'size and height of the building'; 'full

material and manufacturer product information'; 'identification of all safety

critical layers of protection'; 'design intent and construction methodology';

'digital data capture of completed buildings e.g. laser scanning'; 'escape and

fire compartmentation information'; and 'record of

inspections/reviews/consultations'. In addition, the golden thread should

include 'information on the building management system in relation to fire and

structural safety, records of maintenance, inspection and testing undertaken on

the structure and services and evidence that the competence of those

undertaking work on the building was sufficient' (Hackitt 2018, 56).

Hackitt 'recommends that for new builds, a

Building Information Modelling (BIM) approach should be phased in' because

having 'BIM enabled data sets during occupation means that dutyholders will

have a suitable evidence base through which to deliver their responsibilities

and maintain safety and integrity throughout the life cycle of a building'. For

existing buildings, where the original fire safety design information may not

be available, Hackitt (2018, 105) recommends that government 'should work with

industry to agree the type of information to be collected and maintained

digitally'.

Hackitt's recommendations were generally accepted by the government, with proposals for implementation set out in June 2019 in a Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) Consultation Document. This proposed 'that a golden thread of building information is created, maintained and held digitally to ensure the original design intent and any subsequent changes to the building are captured, preserved and used to support safety improvements. In addition, we propose that a key dataset, a sub-set of building information held in a specified format, is required as part of a golden thread. This will enable the building safety regulator to analyse data across all buildings in scope' (MHCLG 2019, 15). Although the regulator will need to be able to check data held in the golden thread, there is no explicit proposal that any or all of this building information should be lodged with the regulator. In Scotland fire safety design information is already required to be lodged with the local authority, and the extension of this principle to the golden thread would be logical. Hitherto this has not been considered possible in England and Wales because building design approval could be carried out either by the local authority or by a private sector Approved Inspector, and in the latter case, the resulting design was seen to be subject to commercial confidentiality. Hackitt (2018, 42) recommended that 'the ability for dutyholders to choose their own regulator must stop', and if that is the case, this barrier to providing the regulator with full access to the golden thread would disappear. However, BIM models often contain information that companies consider to have proprietary value and this is likely to present a barrier to golden thread information being made publicly available.

Challenges for implementation

Hackitt's proposal for the creation of a

golden thread approach to building safety information utilising BIM is welcome

in principle, but like many of her recommendations, will likely prove 'easier

said than done'. BIM has been heavily promoted by the UK government in recent

years, but as others have noted (e.g. Dainty et al. 2017), there are

significant obstacles to its widespread adoption. Three inter-related

challenges may hinder the widespread uptake of BIM: uneven investment across

industry actors; the challenges of data standardisation and harmonisation; and

the lack of adequate competence to use BIM systems.

First, adequate investment in BIM is a challenge

because the UK construction industry comprises a wide range of actors of

greatly varying sizes and resources. The adoption of BIM requires the

allocation of specialist personnel, but the majority of construction industry

operators are SMEs with limited technical capacity. In practice, if a golden

thread of fire safety information is mandated by regulation, then a lowest cost

approach based only on providing the minimum regulatory requirement will be the

path chosen by many. Even where BIM is already being implemented, some extra

work may be needed to incorporate the fire safety golden thread information.

The second issue then arises of exactly

what this information should comprise and how to define it so that is both

useful and unambiguous. BIM is an approach to the digitalisation of physical

and functional building characteristics, but it is not a stable, off-the-shelf

technology. Each instance of the use of BIM will require the organisations

involved to agree on the data to be captured and in what formats. In particular,

there are the typical issues of standardisation and harmonisation that are

raised by such inter-organisational systems (Spinardi et al 1996). Standardisation

is a key issue for the uptake of BIM, but the current situation is that: 'The

ability to capture consistent asset data that is standardised and in a

consistent format remains a challenge for the industry' (Cousins 2019).

Harmonisation of operational practices may also be necessary to ensure that key

actors are using data in the same way.

Third, adequate competence will be required to ensure that data is correctly inputted into the BIM system, and, crucially, that is then used in an appropriate manner in the management of fire safety. A golden thread is no substitute for competent fire risk assessment and building management. A focus on technical solutions to information management should not divert attention from this core issue of competence.

Conclusions

We must await a comprehensive revision of fire

safety regulations to know exactly how Hackitt's recommendations will be implemented.

Although the Hackitt review focussed on Higher Risk Residential Buildings, it

would be wise to address the failings she documented in a systematic manner,

applicable to all types of premises. The proposal that a new regulator should

provide oversight at all stages in the building life-cycle is welcome,

particularly for ensuring that fire safety is maintained during occupation, but

requires a regulator with sufficient resources. With regard to the idea of a

digital golden thread for building information, it might also be useful to

consider whether the information held could go beyond that relevant only to

safety, to include, for example, design and operational data concerning energy

efficiency.

However, whatever the specific role of a golden thread it is unlikely to be easy to do, or a panacea. Hackitt's proposal to use a BIM approach does not make the challenge easier because BIM remains an emergent technology rather than one that is established, stable, and widely used. Rather it may be that any golden thread requirements in new fire safety regulations could provide a driver of BIM implementation, perhaps initially around the narrow requirements of building fire safety. However, whatever form the golden thread information takes, the most important factor will remain the competence of those who make use of it, whether to carry out fire risk assessments and manage building safety or for other building management purposes.

References

Cousins, Stephen (2019). Golden key could unlock Hackitt's golden thread of BIM data. BIM+ http://www.bimplus.co.uk/analysis/golden-key-could-unlock-hackitts-golden-thread-bim/ (Accessed 6 May 2020)

Dainty, A., R. Leiringer, S. Fernie and C. Harty. (2017). BIM and the small construction firm: a critical perspective. Building Research & Information 45(6), 696-709.

Hackitt, J. (2018). Building a Safer Future Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety: Final Report, Cm 9607, London: Her Majesty's Stationary Offfice.

MHCLG (2019). Building a Safer Future: Proposals for reform of the building safety regulatory system: A consultation. London: MHCLG.

Spinardi, G., I. Graham and R. Williams (1996). EDI and Business Network Redesign: Why the two don't go together. New Technology, Work and Employment 11(1).

Spinardi, G., J. Baker and L. Bisby (2019). Post Construction Fire Safety Regulation in England: Shutting the Door Before the Horse has Bolted, Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, Vol. 17( 2), 133-145.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.