www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/cop26-healing-cities.html

Healing Cities: Toward Urban Climate Justice & Slum Health

By Jason Corburn (University of California, Berkeley, US)

The overlapping crises of climate change, COVID-19, and persistent social inequities are acutely felt in cities, particularly among the poor and already vulnerable. Urban climate justice demands a focused strategy to support the healing of these vulnerable communities while also creating new opportunities for them to co-lead more equitable climate resiliency strategies. COP-26 must address 'healing cities for climate justice;' or the need for urgent investments with (not on or for) already vulnerable people and places in order to eliminate existing suffering and urban traumas, while also planning for future prosperity.

What might a healing city for climate justice strategy look like in practice? We suggest this approach is critical for planetary well-being and the survival of the approximately one billion people living in self-built, informal settlements, often called slums (UN 2019). A healing cities for urban climate justice strategy can also move us closer to Sustainable Development Goals 1, 3, 5, 6, 10, 11 and 13, among others (Corburn & Sverdlik 2017).

Consider: Nairobi, Kenya, a city of just under 5 million where about 65% live in self-built, informal settlements that lack access to basic, life-supporting infrastructure and services (Figure 1). In one slum called Mukuru, community-driven research was conducted by residents in partnership with local and international NGOs and universities (Corburn et al. 2019) which led to the community being designated a Special Planning Area (SPA) (Muungano Alliance 2021). This designation ensured a new redevelopment plan would be drafted with resident input and expertise, and that the improvement plan must address the multiple traumas afflicting Nairobi's slum dwellers, including: climate change risks from flooding and disease, social and physical exclusion, lack of water, sanitation and energy infrastructure, secure tenure and environmental injustices from toxic dumping and localized air pollution (Horn 2021). The county government was also involved, as were national governmental institutions. Findings were shared with tens of Mukuru SPA 'consortium' partners and, with resident input, turned into an integrated upgrading plan. The improvement strategies included prioritizing the needs of the most vulnerable, such as reducing flooding risks for the poorest of the poor living along river riparian areas, delivering water and safe sanitation to women, and creating new public spaces for youth to play, create and learn (Anderson 2014).

When

COVID-19 emerged in 2020, the Nairobi Metropolitan Services (NMS) was empowered

by the Kenyan government to lead the response in many informal

settlements. Mukuru was one of the first

places selected for investments, in part because residents were already mobilized,

had already developed a plan and many built environment projects were 'shovel

ready' (Weru & Cobbett 2021).

Instead of just getting temporary services and treatment, which would

have been typical during an emergency response, Mukuru received permanent,

healing-focused, life-supporting built environment investments. Kilometers of

roads, sidewalks and bicycle paths were tarmacked, connecting previously

disconnected villages within the community and linking the entire settlement to

services, jobs, schools, and the benefits of the entire city (Figure 2).

The Mukuru projects are promoting healing and urban climate justice by reducing vulnerability today while building the physical, social and governance infrastructure for resident prosperity moving forward (Sverdlik et al. 2019). While incomplete and an on-going project, Mukuru's transformation reflects the values of how a city can invest in its least-well-off places and populations first, while delivering benefits to everyone (Ng'ang'a 2021).

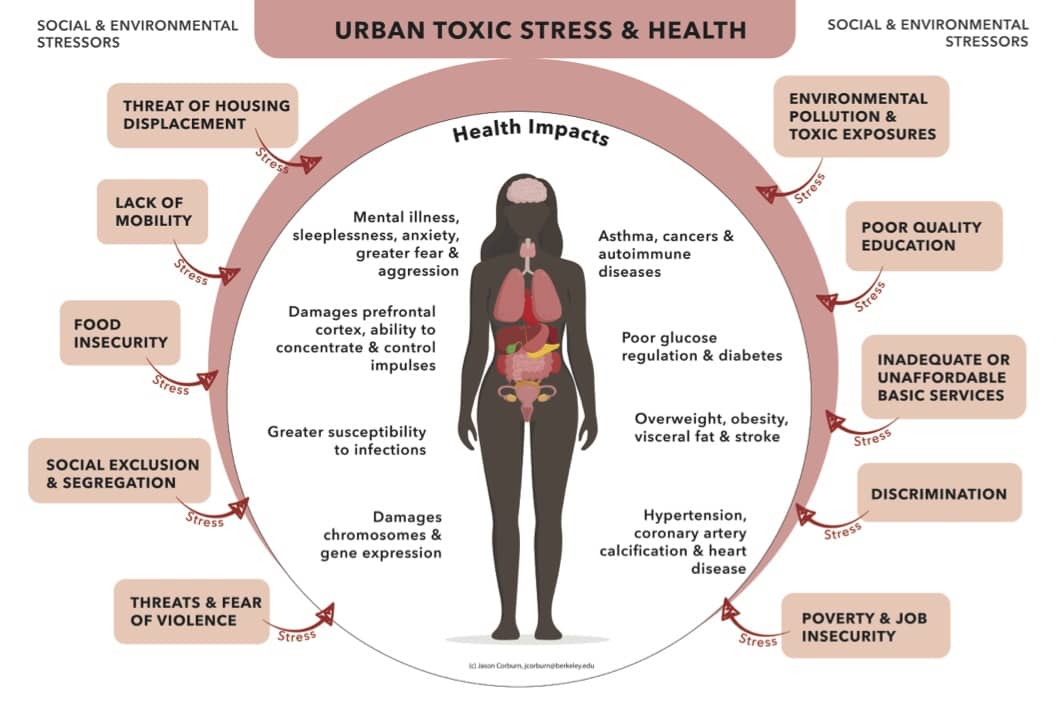

As COP-26 considers strategies to reduce planetary suffering, the lessons from Mukuru must inform urban design and planning practice. First, practitioners must work with the poor and vulnerable communities to identify the toxic stressors (Figure 3) - or those inequalities contributing to suffering, trauma and disease - not rely on professional 'experts' alone (Corburn 2017). Next, residents, civil society groups, universities, and local governments must co-create actionable plans to support healing, which means focusing design and investments on reducing trauma and stress through a combination of physical infrastructure, social programs and democratic decision-making (Ellis & Dietz 2017). Third, professionals must practice humility and learn-by-doing with local people, not acting for or 'on' them. Finally, cities that heal and promote climate justice must adapt as they learn what is and is not supporting the well-being of the poor and marginalized communities. A one size fits all approach will not heal those suffering today, and will not contribute to prosperity for all moving forward.

References

ABC News. (2021). Vending machines bring safe, cheap water to Nairobi slums. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-09-18/kenya-water-vending-machines-mukuru-slums/100465320

All Africa. (2021). Kenyatta commissions five new hospitals in Nairobi. https://allafrica.com/stories/202107070114.html

Anderson, M. (2014). Nairobi's female slum dwellers march for sanitation and land rights. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/oct/29/nairobi-slum-dwellers-sanitation-land-rights

Corburn, J. (2017). Urban place and health equity: critical issues and practices. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(2), 117. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020117

Corburn, J., Asari, M.R., Wagner, A., Omolo, T. Chung, B., Cutler, C. Nuru, S., Ogutu, B., Lebu, S. & Atukunda, L. (2019). Mukuru Special Planning Area: Rapid Health Impact Assessment. Berkeley: Center for Global Healthy Cities. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/591a33ba9de4bb62555cc445/t/5e6d77579988a61549be14a8/1584232291593/Mukuru+Nairobi+Health+Impact+Assessment+2019_UCB.pdf

Corburn, J. & Sverdlik, A. (2017). Slum upgrading and health equity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(4): 342. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14040342

Ellis, W.R., Dietz, W.H. (2017). A new framework for addressing adverse childhood and community experiences: the building community resilience model. Academic Pediatrics,17(7S):S86-S93. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.12.011

Horn, P. (2021). Enabling participatory planning to be scaled in exclusionary urban political environments: lessons from the Mukuru Special Planning Area in Nairobi. Environment and Urbanization. doi:10.1177/09562478211011088

Kinyanjui, M. (2021). NMS projects slowly changing the face of Mukuru slums. The Star. https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2021-08-16-nms-projects-slowly-changing-the-face-of-mukuru-slums/

Muungano Alliance (2021) Mukuru SPA. https://www.muungano.net/mukuru-spa

Ng'ang'a, J. (2021). Projects to upgrade informal settlements on top gear. Kenya News Agency. https://www.kenyanews.go.ke/projects-to-upgrade-informal-settlements-on-top-gear/

Sverdlik, A., Mitlin, D. & Dodman, D. (2019). Realising the Multiple Benefits of Climate Resilience and Inclusive Development in Informal Settlements. New York: C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/C40-Climate-Resilience-Inclusive-Housing.pdf

United Nations. (2019). SDGs progress report: Goal 11. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/goal-11/

Weru, J. & Cobbett, W. (2021). Slum upgrading in Kenya: what are the conditions for success? Thomson Reuters News Foundation. https://news.trust.org/item/20210225133836-td97u

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Living labs as ‘agents for change’ [editorial]

N Antaki, D Petrescu & V Marin

Post-disaster reconstruction: infill housing prototypes for Kathmandu

J Bolchover & K Mundle

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.