www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/reviews/routledge-companion-architecture-social-engagement.html

The Routledge Companion to Architecture and Social Engagement

Edited by Farhan Karim. Routledge, 2018, ISBN: 9781138889699

Carin Combrinck (University of Pretoria) welcomes this book for its timeliness, sense of urgency and advancement of a missing pillar of sustainability. Redefining architecture for its social engagement and public contribution will have important implications for practice, teaching and research.

It is highly meaningful to read the Routledge Companion to Architecture and Social Engagement in this particular moment in history, when half of humanity is confined to their homes during the Covid-19 pandemic. Nils Gore's section on Reconceiving Professionalism especially strikes a chord:

"In 2011 I heard Thomas Fisher, then dean of the University of Minnesota College of Design, give a talk where he briefly recounted the establishment of the public health profession, as distinct from that of medicine, and in that talk, suggested that something similar ought to happen for what he called 'public architecture' (and what we may now have settled on calling 'public interest design'), meaning the design of the built world that needs to happen outside the bounds of the bespoke project on the individual piece of land which typifies the cast majority of architects' work. He used the example of a pandemic which might start in a squatter settlement in the developing world, incubating and flourishing because of the lack of adequate infrastructure, and that rapidly spreads around the world, as a result of the mobility of all people everywhere. The costs of dealing with a pandemic would be enormous, and might be prevented with a much less costly and better-designed housing settlement with adequate infrastructure. Fisher argued that the costs of providing public design services would be a better value proposition than waiting for the outbreak to occur and then dealing with the catastrophic outcomes. This is but one example of a public interest project. We can include community design issues such as alternate transit systems, energy systems, the food system, design for equity, racial and social justice, affordable housing, and design for public awareness as other projects needing attention." (Gore 2018: 122)

A sense of haste pulsates throughout the book, with a shared call to action that seems to unite the myriad of voices speaking out from these voluminous pages. The book constitutes a critical mass of scholars drawn from different countries who are united to redefine architecture as a discipline of social purpose. The book confirms that we are not alone: scholars, educators and practitioners argue the importance of looking beyond the self-referential limitations of our discipline. It successfully explains there is more to be done and other ways of getting it done than merely focusing on the product of architecture. This includes a greater emphasis on the relationships and complexity involved in the processes of design, construction and appropriation of space, bearing in mind the consequences and impacts of these fundamentally political and cultural processes.

The book suggests that socially engaged architecture is important and relevant, from its deeply philosophical considerations through to its teaching and practice. No stone has been left unturned here, with every notable reference included to support a comprehensive and rigorous discourse. Even the heroes of this genre have been regarded under the magnifying lens of critical contextualisation thereby enabling the reader to understand the substantive historical grounding on which to build a continuing body of scholarship and praxis.

This book is a comforting and calming experience to read during an anxious time. The curation of the multiple voices and perspectives in this volume will challenge the reader's perceptions and imagination. It may also confirm some readers' earlier suspicions and propositions. The book is uncannily appropriate to its time and promises to become one of the most important contributions to a discourse that needs to move from the margins to the mainstream with utmost urgency.

The book's structure is easily accessible and logical, with a chronological approach that makes it simple to follow and to reflect back on the work. The organisation considers the philosophical discourse; historical perspective; questions of ethics and legitimacy; professional and educational implications, illustrated by way of practical applications of projects at varying scales.

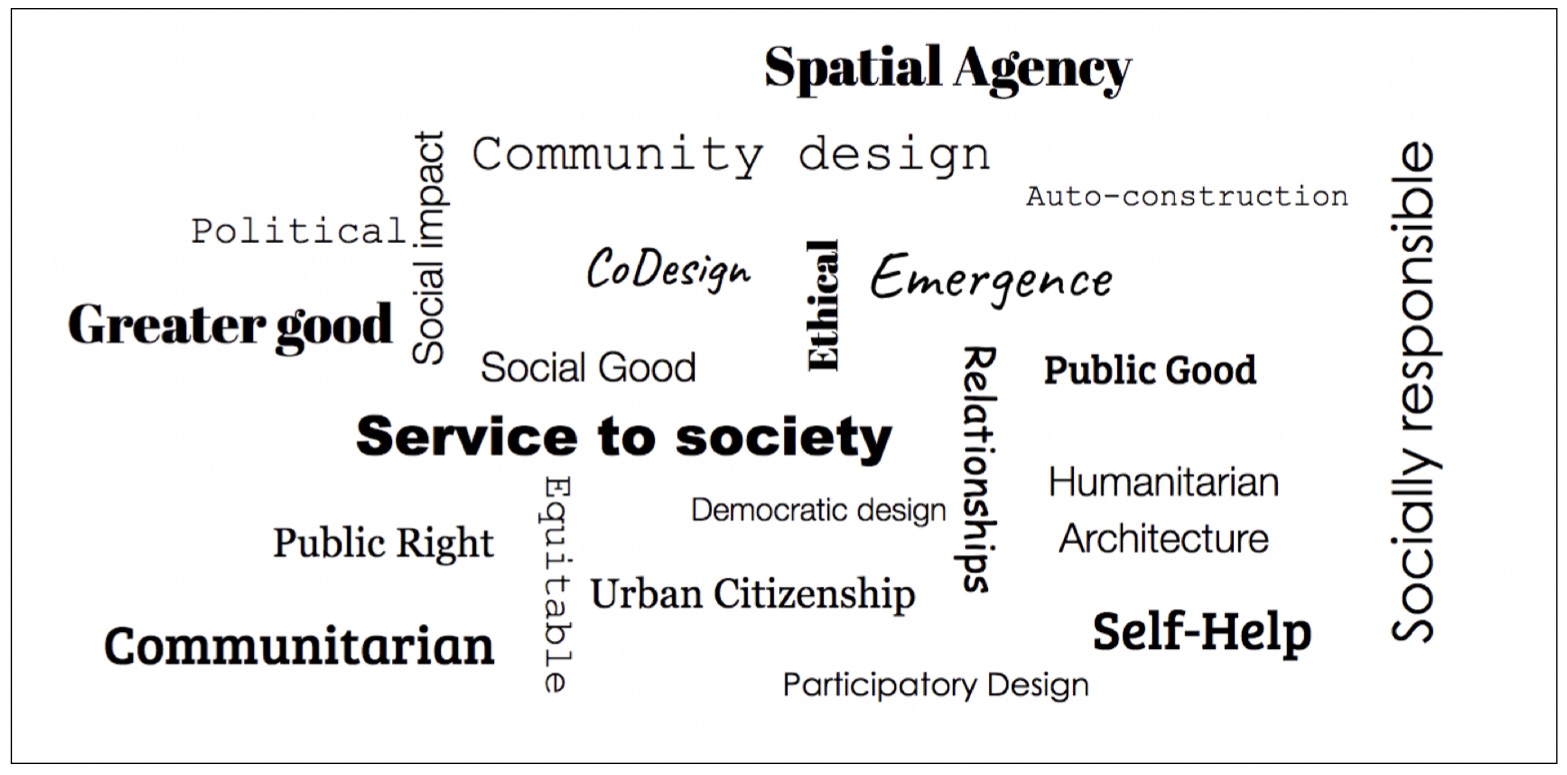

This organisation frames the main themes in the book, which are captured in the wordcloud below. The themes converge around a paradigm shift away from individualist concepts of control and self-interest towards a collective view of empathy and service to society. Such service is considered from a perspective of agency and respect for local narratives and power structures, where the notion of 'expertise' is redefined to include all participants as valuable collaborators in the co-creation of the built environment. Epistemic diversity becomes more highly valued in this paradigm, where a variety of knowledge systems may serve to address the complex challenges we are all facing.

It is clearly the editor's intent to offer a comprehensive encyclopaedia of the current discourse on socially engaged architecture. Without a doubt, the book has succeeded in this ambition and promises to become an authoritative voice and source of reference to anyone already interested in this field or hoping to familiarise themselves with it. The wide range of critical viewpoints leaves the reader in no doubt as to the challenges and opportunities that are involved in all aspects of this genre in architecture, extending by its nature an open invitation to continue and contribute to the evident fluidity of the discourse.

This book offers a rich platter of thought for researchers to test, to build on, to compare and to frame continuing investigations. Provocations and examples of successes and failures may be referred to with ease to situate alternative hypotheses. From heavy-handed interventions in Zanskar, India (refer to Chapter 9 by Carey Clouse) to the deeply thought-provoking reflections on healing after the Rwandan genocide (refer to chapter 17 by Yutaka Sho), the basis has been established from which to identify a well-grounded normative position. Policy makers and practitioners will find answers and suggestions that may serve to support meaningful shifts in direction, as the work presented is rigorous and steeped in credibility and gravitas. For educators, the book is a gift because it provides a well-considered, well-rounded and clear demonstration of a substantial, relevant and significant body of thought.

Introducing and framing the

professional distinction of Public Interest Design (PID) (refer specifically to

Chapter 25 by Joongsub Kim) promises a truly useful and meaningful opportunity

to resolve some of the tensions within the academic accreditation conundrum in

which this discourse often finds itself. By framing the collective endeavour in

this way, some of the institutional resistance that is often mentioned in the

book may be overcome. As part of the need to move beyond the traditionally held

margins, PID may lead to greater impact on the profession and by implication,

on society.

Not all stakeholders will be interested in reading the book from cover to cover, nor is it necessary to do so. It is possible for stakeholders to choose what is of value to them and have a reliable resource available to support their cause in arguing for greater social engagement in architecture. It is therefore my view that everyone who is concerned with a process of social engagement ought to have a copy on the shelf for continued reference. The publisher's price (ca.£152) may be considered contrary to the socially inclusive message in the book.

This book is a trove of inspiration and confirmation. It successfully argues and demonstrates an alternative pathway for architects and architectural students to make more meaningful contributions to society. The need to do so is reflected in the words of the current International Union of Architects (UIA) president, Thomas Vonier, whose call on 6 April 2020 has recently gone out:

"When architects created the UIA in 1948, the world was barely past the worst cataclysm in memory: World War II. The human toll of that war was horrific, and it left many cities and economies in shambles... Today, just as in 1948, architects must unite in service to society, bringing global perspective and vision. As the profession's international organisation, it is our role to highlight relevant research, promote information sharing and advocate for sound policies."

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Living labs as ‘agents for change’ [editorial]

N Antaki, D Petrescu & V Marin

Post-disaster reconstruction: infill housing prototypes for Kathmandu

J Bolchover & K Mundle

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.