www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/harnessing-design-research.html

Harnessing Design Research to Encourage Alternative Futures

Both research and practice have a key role in developing positive, shared visions for the built environment

Doina Petrescu (University of Sheffield) explains how design research and architectural practice can respond to multiple crises (resource depletion, overconsumption, climate change, biodiversity loss, etc). By developing new shared visions of how to live it is possible to create a future built environment that is just and equitable.

Design and the future

Research into architecture and cities has recently known a design turn in relation to researching for the future. Design, as mode of inquiry, is well placed to deal with complexity and address the 'wicked problems' of the uncertainty of the future (Rittel & Weber 1973) meaning the future itself can be a design problem (Reeves et al. 2016).

Fraser (2013) defines architectural design research as:

'the processes and outcomes of inquiries and investigations in which architects use the creation of projects, or broader contributions towards design thinking, as the central constituent in a process which also involves the more generalized research activities of thinking, writing, testing, verifying, debating, disseminating, performing, validating, and so on'.

The growing interest in design research has developed in parallel with a shift from traditional scholarly research to an 'in-practice' model based on the knowledge gathered 'in the context of application'. This shift recognises design practice itself as a locus for research and, thus, a source of knowledge proving other essential modes of knowing, and ways of thinking-approaches that are often absent in other disciplines but are increasingly essential today. This may involve addressing ill-defined or unknown problems, such as those related to the future, through iterative processes in which assumptions are challenged, problems are reframed, and ultimately, innovative solutions are developed, prototyped, and tested.

Designing transition

The present can be characterised as 'transition times'. This is due to the need to address the complexities and uncertainties related to climate crisis, resource depletion, biodiversity loss, species extinction, energy crisis, etc., as well as the ways society can engage with the transition towards a more sustainable future. The concept of 'transition' is central to various contemporary discourses and initiatives focused on how change manifests and can be catalysed or directed in complex systems (Irwin 2015). The term and concept of 'transition' has become central in built environment policies (EU Green Deal / Green Transition), programmes and funds (Clean Energy Transition, Driving Urban Transition, Just Transition Fund) and grassroots movements (Transition Network, Community Energy, etc.).

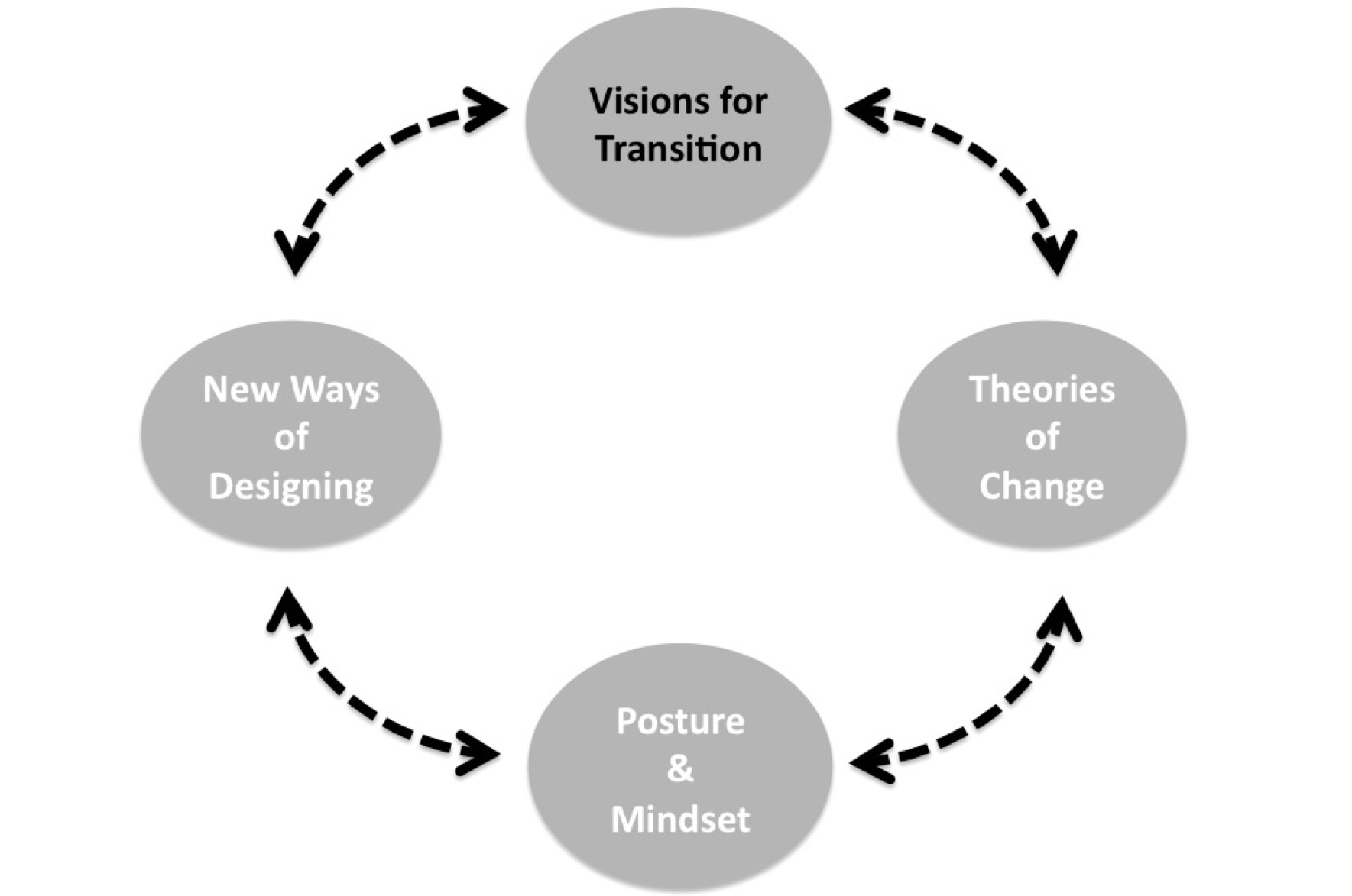

Transition Design argues that design plays a key role in these transitions and applies an understanding of the interconnectedness of social, economic, political, urban and natural systems to address problems at all levels of spatio-temporal scale, ultimately improving quality of life. Design theorists Irvine et al. (2015) propose a Transition Design framework outlining four mutually reinforcing and cyclical co-evolving areas of knowledge, action and self-reflection.

In this framework, the Visions for the future are based upon the reconception of entire life-styles that are human scale, place-based, but globally connected in their exchange of technology, information and culture. New ways of designing will help realise these visions but will also evolve them. These transformations need continual change in Posture and Mindset. Living in transitional times requires a mindset and posture of openess, mindfulness, self-reflection, a willingness to collaborate, based upon a new, more holistic worldview and ecological paradigm. New theories of change will therefore reshape designers' mindsets and postures. Therefore, the related 'new ways of being' in the world will motivate the search for new, more relevant knowledge (Irwin et al. 2015).

Over the past decade, there has been a rich production of cultural and ecological transition narratives and discourses in both the Global North and South. In the North, concepts and movements such as degrowth, commoning, conviviality, co-resilience, transition towns, and a wide array of transition initiatives are emerging (Escobar 2015; Petrescu et al. 2016). In the Global South, key transition narratives and radical alternatives to 'development' include buen vivir (collective well-being), rights of nature, communal logics, and civilizational transitions, particularly as they unfold in some Latin American countries. (Kothari et al. 2019) At present, in both global regions, these initiatives remain sporadic and constrained, struggling to scale due to resistance from local and global capitalist forces, including unregulated markets, networks of influence, centralized power structures, administrative bureaucracy, fragile democracies, and so on.

However, these frameworks propose a rethinking of the ontological basis of design, being aware that the act of designing is designing lifeworlds that, in turn, shape and design us (Willis 2006). Therefore, it is crucial to consider the kind of lifeworlds being designed, as these will influence the future and, in turn, shape the societies that inhabit them. The decisions made in identifying, imagining and intervening in particular realities inevitably raise political questions.

Politics of design

There is an urgent need to expand political reflexivity in designing visions of the future. This means questioning the politics of what or who is present in that future, as well as which or whose social norms, practices, and structures are (re)produced or challenged by those visions. (Mazé 2014). This is particularly important for discussions about architecture and cities.

Therefore, the role of designers is not only to make superficial claims about 'solving problems' or 'making a difference'. Instead, they should use designed visions of the future to encourage alternative thinking and action and also invite others to join the conversation and participate in the designing process as a political act.

Other design drivers may approach things differently. Therefore, we need feminist and decolonial perspectives (Schalk et al. 2017; Lindström et al. 2017; Petrescu 2007), the inclusion of pluriversal visions (Escobar 2018), which bring positions and perspectives rooted in diverse places and histories, and 'designs when everybody designs' (Manzini 2019). Design research can then primarily serve to build a democratic design agency that aims to 'consciously intervene in the world', requiring diverse design skills and an 'enabling ecosystem' for and by citizens (Manzini 2019).

Changes for the future

Despite these important dimensions, the significance of design futuring is not yet fully recognized in architecture. There is a pressing need for increased support for design research and education, including the development of more sources and methods of funding. Additionally, there is a need for the knowledge and skills of architects to be reframed and developed strategically (Samuel 2018).

Currently, in the UK, alongside specific programmes from professional bodies such as RIBA, research funders (e.g. Design Council, UK Research and Innovation *UKRI), and Innovate UK) have established dedicated grant programmes and funding streams for design research. At the EU level, the New European Bauhaus (NEB) programme supports design innovation based on its three core principles: sustainability, inclusion, beauty. However, we may need more targeted funding streams that specifically support transition designs, challenging the current techno-centric, modern, gender-biased, and Western-centric orientations.

Changes have started in architectural education. Masters and PhDs in design and practice programs are proliferating. These programmes would benefit from more research into nature-centred and care-focussed design, ecological restoration, pluriversal design, alternative futuring, indigenous wisdom, cosmopolitan localism, decolonising approaches etc. New institutions and initiatives (e.g. the African Futures Institute founded by Lesley Lokko in Accra and her The Laboratory of the Future at the 2023 Venice Biennale in Architecture (Lokko 2023)) are great examples of ways of decentring and reorienting the debate on the future by including new territories, visions and people ignored until now.

Conclusions

Design education needs to address diverse social and environmental challenges (climate change, resources depletion, biodiversity loss, forced displacements and migrations, etc) in a just way. Those affected by these challenges must be involved. Design research can be a driver for civic university programmes playing a catalyst role in co-producing knowledge in cities and communities, through the creation of design-based living labs, eco-civic hubs and urban classrooms (Belfield & Petrescu 2024). Activist initiatives such as Architects Declare or Architects Climate Action Network in UK or R-Urban and Le Mouvement pour une Frugalité heureuse et créative in France indicate other transition directions in which design research could develop in architecture.

Robust two-way knowledge exchanges are needed, where design knowledge can be shared with stakeholders, and where stakeholders can contribute their insights to the design process. Furthermore, more cross-disciplinary research is necessary, allowing design methods to contribute to other research disciplines. Design methodologies such as co-mapping, co-designing, co-making have the potential to be powerful drivers for participation and co-production in interdisciplinary projects.

Initiatives including design labs and deliberative forums and frameworks such as Deliberativa, Decidim, Citizen Lab, Dark Matters Labs, Cultures for Resilience and others use design methods to engage citizens in decision-making, visioning and prototyping of futures (Dryzek 2002; Rezai & Erlhoff 2021). However, more design labs are needed to shape progressive policy in architecture and planning, as well as more design-based civic assemblies to enable citizens to open up the governance process and participate in deliberation and policymaking.

In conclusion, the role of design, the design process and practice-based research in architecture are crucial for shaping the future. This field must continue its ontological reframing, moving beyond techno-centric, gender-biased and Western-centric perspectives. It should encourage all design professionals and stakeholders to embrace uncertainty and hybridity and engage more profoundly-philosophically, politically, and ethically-in addressing the current challenges. By doing so, they can actively contribute to the creation of more just, diverse and sustainable urban lifeworlds now and in the future.

References

Belfield, A. & Petrescu, D. (2024). Co-design, neighbourhood sharing, and commoning through urban living labs. CoDesign, 1-24.

Dryzek, J.S. (2002). Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberals, Critics, Contestations. Oxford University Press.

Fraser, M. (2013) Design Research in Architecture: An Overview, London: Ashgate Publishing.

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

Escobar, A. (2015). Degrowth, postdevelopment, and transitions: A preliminary conversation. Sustainability Science, 10(3), 451-462.

Irwin, T., Kossoff, G. & Tonkinwise, C. (2015). Transition design provocation, Design Philosophy Papers, 13(1).

Irwin, T. (2015). Transition design: A proposal for a new area of design practice, study and research. Design and Culture, 7(2), 229-246.

Jonas, W., Zerwas, S, &. von Anshelm, K. (2015). Transformation Design: Perspectives on a New Design Attitude. Boston: Birkhäuser.

Kothari, A., Salleh, A., Escobar, A., Demaria, F. & Acosta, A. (eds) (2019). Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary. New Delhi: Tulika Books.

Lindström, K., Mazé, R., Forlano, L., Jonsson, L. & Ståhl, Å. (2018). Editorial: Design, research and feminism(s). In Storni, C., Leahy, K., McMahon, M., Lloyd, P. and Bohemia, E. (eds.), Design as a catalyst for change - DRS International Conference 2018, 25-28 June, Limerick, Ireland.

Lokko, L. (ed.) (2023). Biennale Architecttura 2023: The Laboratory of the Future. Catalogue of the Venice Biennale of Architecture 2023.

Mazé, R. (2014). Politics of designing visions of the future. Journal of Futures Studies, 23(3): 23-38.

Manzini, E. (translated by Rachel Coad). (2019) Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation, Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Petrescu, D. (ed). (2007). Altering Practices: Feminist Politics and Poetics of Space. London: Routledge.

Petrescu, D., Petcou, C. & Baibarac, C. (2016). Co-producing commons-based resilience: lessons from R-Urban. Building Research & Information, 44(7), 717-736.

Reeves, S., Goulden, M. & Dingwall, R. (2016). The future as a design problem. Design Issues, 32 (3): 6-17.

Rezai, M. & Erlhoff, M. (eds). (2021). Design and Democracy: Activist Thoughts and Examples for Political Empowerment. Boston: Birkhäuser.

Rittel, H. W. & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning, Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155-169.

Samuel, F. (2018). Why Architects Matter: Evidencing and Communicating the Value of Architects. Routledge: London

Schalk, M., Kristiansson, T. & Mazé, R. (eds).(2017). Feminist Futures of Spatial Practice: Materialisms, Activisms, Dialogues, Pedagogies, Projections. Baunach: Spurbuchverlag.

Willis, A.M. (2006). Ontological designing. Design Philosophy Papers, 4(2), 69-92.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.