www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/carbon-metrics-real-estate.html

Carbon Metrics Can Help the Real Estate Sector

How can the real estate and construction industries use carbon metrics to apportion responsibility and radically reduce their GHG emissions?

Users, investors and policy makers need reliable information in order to take effective action against climate change. It is clear that KPIs must be derived starting from the reduction of GHGs, and that the built environment (i.e. real estate and construction) should accept one of the largest shares of this burden. Sven Bienert (University of Regensburg) reflects on the B&C special issue CARBON METRICS FOR BUILDINGS AND CITIES: ASSESSING AND CONTROLLING GHG EMISSIONS ACROSS SCALES and argues the industry needs to urgently agree on what are appropriate and just measures for the industry, particularly how GHG budgets should be distributed.

Action is needed

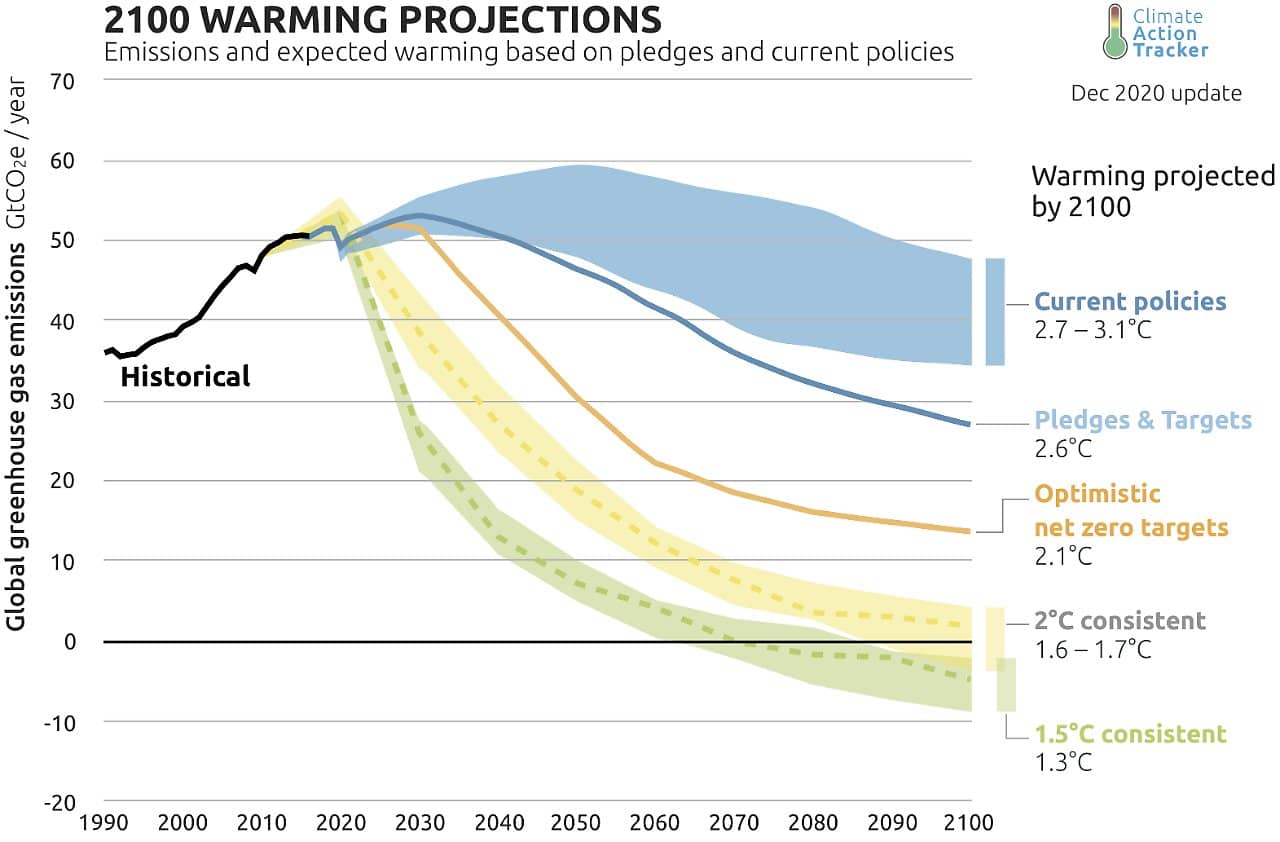

The findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) are indisputable (IPCC 2019). The oceans are heating up, the permafrost is thawing, and the sea level is rising. It is clear that the current global warming is primarily caused by mankind. For years there has been general consensus that rigorous action is needed to stop these developments. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Paris Agreement of 2015 has set the goal of limiting the global average increase in temperature to 1.5 - 2 C compared to preindustrial levels (UNFCCC 2015). How can this be achieved? The answer is clear - by radically curbing GHG emissions in order to halt climate change. However, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to limit GHGs by individual countries are until now insufficient to meet the Paris Agreement's climate goals, and national regulations to fulfil NDCs are also running behind the curve (Climate Action Tracker 2020).

National measurable GHG emission targets are needed. The remaining global carbon budget and the carbon intensity (CO2e) of individual assets are the pivotal points. Lützkendorf (2020) correctly states that the essential task is currently "quantification, allocation, assessment and control", as well as a fair share of the burden being distributed among the stakeholders. On a global scale, researchers have quantified the remaining anthropogenic global carbon budget that can be emitted by mankind until 2050 in order to avoid exceeding the 1.5 or 2 C targets. (CRREM 2020, Habert et al. 2020 or Steininger et al. 2020).

Real estate and construction have a significant share (about 30%) of all global anthropogenic GHG emissions (GlobalABC 2018). It is quite clear that those involved in the creation and operation of the built environment cannot extricate themselves from this responsibility. In addition to altruistic concerns, there is growing pressure from emerging consumer and investor demands as well as increasing regulatory requirements. The current CO2 pricing in Germany (German Government 2020) and the increasing EU climate targets (European Commission 2020a) are just two pressing examples. In any case, it is ultimately a choice between a rock and a hard place for our industry; do the transition risks dominate through necessary decarbonization efforts or do the physical risks dominate through uncontrolled climate change. In this respect, ignoring and wishful thinking as a means of dealing with climate risks is not an approach at all, but abject failure.

Key challenges for the real estate sector

The mission is clear and simple: reduce your carbon footprint! For our industry, this would mean working on aspects like the carbon intensity measured in CO2e/m²/year (see Lützkendorf & Frischknecht 2020, Habert et al. 2020, CRREM). "Green wash" by investors and the real estate industry is not completely gone, but my perception is that an increasing number of companies are delving deeply into carbon accounting supported by appropriately qualified staff and the necessary resources (e.g. see participants in CREEM and volume development).

What are the remaining challenges and who or what could assist in overcoming them?

1. Data availability remains limited in the real estate industry. This is partly due to the tenant-landlord dilemma which is a problem of split incentives. Green-leases and data-sharing procedures need to be fostered within national legal systems and voluntary initiatives by the industry itself. Increased transparency and accessibility to data are needed.

2. Although carbon intensity sounds simple, it means getting the right figures (data quality and data standards). A solution could be improved alignment and industry support for approaches like the newly formed European Commercial Real Estate Data alliance (ECREDA). Standards for floor space (IPMS) have been introduced and must be widely accepted in order to provide a consistent reference for intensity. Other aspects are occupancy-adjustment or normalization for climate conditions (HDD/CDD). A good example of standards and definitions is the new EU taxonomy (European Commission 2020b). It defines (once again) what is meant by "sustainable real estate". Regulation is certainly positive and important. But the (new) regulation of definitions reveals one thing above all: there is still a compelling need to state clearly what we really mean by "sustainability".

3. Precautions against "green wash" are still needed, e.g. clear standards also for the use of market-vs. location-based emission factors. Merely buying green energy is not the same as working on energy efficiency with regard to energy retrofits for a specific building.

4. Embodied carbon is now recognized as an industry issue e.g. Waldman, Huang and Simonen (2020), Andersen et al. (2020) or Kuittinen & Häkkinen (2020). The trade-off between grey emissions associated (with necessary investments and energy retrofits) need to be outweighed by operational savings. More research is essential to address this dilemma.

5. A clear and fair process for the allocation of resources as well as decarbonization responsibilities and budgets is needed for certain countries and certain use types. The overall remaining global carbon budget (see above) needs to be disaggregated to lower levels - those of countries, sectors, cities, districts, buildings or consumers. Approaches like Steininger et al. (2020) and Frischknecht et al. (2020) constitute some first steps to achieving these aims. Frischknecht et al. (2020) rightly emphasize that the use phase accounts for the largest share of emissions and that this should be the main focus when calculating budgets. To achieve this, the system boundaries must be defined correctly. Projects like CRREM address this aspect and indeed consider the operational carbon budgets and utilize clear decarbonization pathways that are aligned with the Paris Agreement, and set long-term requirements (CRREM 2020).

6. A whole-building approach is the only way forward to decarbonize standing assets. Presently, many landlords are reluctant to accept that they are supposed to focus on more than just "common space".

7. Circular approaches, as shown by Andersen et al. (2020), are central to our industry. However, as these authors show, LCA approaches continue to be subject to many limitations and challenges. Nevertheless, cycles and a cautious, aware selection of materials should increasingly be brought to the forefront of consideration. To this end as well, more data is needed.

8. Lützkendorf (2020) and other authors provide a positive way forward in this special issue. But ultimately, it is also a question of leadership: will industry leaders accept that climate risks are affecting their financial viability and property values? In the short term, it is necessary to invest a bit more in order to protect long-term value for shareholders. It is emphatically not a question of altruism to invest in decarbonization projects. Instead, it is the way to ensure robust financial performance.

A personal conclusion

My perception is that both politicians and industry stakeholders are now pulling in the same direction and lately with considerable strength. However, given the overall remaining carbon budget, I am nevertheless convinced that much more effort is still needed. With publications like the papers in this special issue Carbon Metrics for Buildings & Cities: Assessing and Controlling GHG Emissions Across Scales, research is contributing to the most relevant questions in our sector in a compelling and desperately needed manner. Far more deep research and leadership are needed in order to address our share of responsibility, so as to ensure a transition to a sustainable (real estate) future.

References

Andersen, C. E., Kanafani, K., Zimmermann, R. K., Rasmussen, F. N., & Birgisdóttir, H. (2020). Comparison of GHG emissions from circular and conventional building components. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 379-392. http://doi.org/10.5334/bc.55

Climate Action Tracker. (2020). Global Temperatures. https://climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/

CRREM. (2020). From global emission budgets to decarbonisation pathways at property level: CRREM downscaling and carbon performace assessment methodology. Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM). https://www.crrem.org/pathways/

European Commission. (2020a). State of the Union: Commission raises climate ambition and proposes 55% cut in emission by 2030. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_1599

European Commission. (2020b). EU taxonomy for sustainable activities. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en

German Government. (2020). Climate Action Programme 2030. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/issues/climate-action

GlobalABC. (2018). Global status report: Towards a zero-emission, efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector. International Energy Agency (IEA) for the Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction (GlobalABC). https://www.worldgbc.org/sites/default/files/2018%20GlobalABC%20Global%20Status%20Report.pdf

Habert, G., Röck, M., Steininger, K., Lupisek, A., Birgisdottir, H., Desing, H., … Lützkendorf, T. (2020). Carbon budgets for buildings: harmonising temporal, spatial and sectoral dimensions. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 429-452. http://doi.org/10.5334/bc.47

IPCC. (2019). Summary for policymakers. Special Report on climate change and land. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/

Kuittinen, M., & Häkkinen, T. (2020). Reduced carbon footprints of buildings: new Finnish standards and assessments. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 182-197. http://doi.org/10.5334/bc.30

Lützkendorf, T. (2020). The role of carbon metrics in supporting built-environment professionals. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 676-686. http://doi.org/10.5334/bc.73

Lützkendorf, T., & Frischknecht, R. (2020). (Net-) zero-emission buildings: a typology of terms and definitions. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 662-675. http://doi.org/10.5334/bc.66

Steininger, K. W., Meyer, L., Nabernegg, S., & Kirchengast, G. (2020). Sectoral carbon budgets as an evaluation framework for the built environment. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 337-360. http://doi.org/10.5334/bc.32

UNFCCC. (2015). Adoption of the Paris Agreement. New York: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Waldman, B., Huang, M., & Simonen, K. (2020). Embodied carbon in construction materials: a framework for quantifying data quality in EPDs. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 625-636. http://doi.org/10.5334/bc.31

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Living labs as ‘agents for change’ [editorial]

N Antaki, D Petrescu & V Marin

Post-disaster reconstruction: infill housing prototypes for Kathmandu

J Bolchover & K Mundle

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.